8-16-11 - Tozen

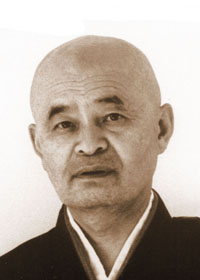

Akiyama Roshi

8-16-11 - Tozen

Akiyama Roshi

Tozen founded the Milwaukee Zen Center and was resident teacher at the Anchorage Zen Community

Here are talks of Tozen's that were published by the MZC back then which will be added to cuke.com one by one. He's retired and living near us here in Santa Rosa so I got him to send these to me sort of almost against his will. I thought they were good to share. Thanks Tozen, also known by his self-proclaimed moniker of Hopeless Tozen. - dc

Joshu's Mu and the Life of No Merit - audio lecture

The following lectures were updated here on cuke 7-28-12 in honor of a lunch I'm having with Tozen and Shohaku Okumura. - dc

Vol. 1, No. 1 (of their publication from back then)

January, 1986

EVERY YEAR IS A GOOD YEAR

A Happy New Year!

It is customary all over the world to observe New Year’s Day. In Japan, New Year’s Day is the happiest day of the year. Japanese people send New Year’s cards, put up beautiful decorations, eat special dishes, visit Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples to pray for happiness, good health and prosperity in the new year, and enjoy several days off to celebrate the beginning of the year. Even in the United States, where Christmas is much more important, people celebrate with New Year’s Eve parties to welcome in the new year.

Is New Year's Day really happy?

New Year’s Day is in fact only one of 365 days and is not essentially different from the other 364 days. Human beings attach special meanings to it for their own convenience. Should we not celebrate New Year’s Day, then?

The bamboo is a strong plant. Strong winds cannot blow it down. A delicate branch bent by the snow straightens when the snow melts in the sunshine. The reason it is so strong is that it has joints. If it had no joints, it would not be so flexible and strong. Human beings may need some joints as a change in their lives. The celebration of New Year’s Day is one of the joints to give their lives variety and refresh them. But, at the same time, we must realize that it is a joint created by human beings; it does not occur naturally.

* * * * * * * * * *

There is a famous koan in Hekiganroku with which you may be familiar. It goes as follows:

Unmon addressed the assembly and said, “I do not ask you about the days before the fifteenth of the month. Come and give a word about the days after the fifteenth.” And he himself answered for them,

“Every day is a good day.”

We should not be concerned with days. Whether it is before or after the fifteenth of the month, every day must be a good day. Following his example, we should also say, “Every week is a good week,” “Every month is a good month,” “Every year is a good year.” In other words, “Every moment is a good moment.” If we live like that, we do not need to say, “Happy New Year!” But how can we make it so?

We usually think of “favorable or convenient to myself” as “good” or “happy” and that a day or a year full of events which are “favorable or convenient to myself” is “good” or “happy.” However, the world does not always go as we wish. We cannot live without “unfavorableness” or “inconvenience.” In order to be able to say even “unfavorable” or “inconvenient” times are “good” or “happy,” we must accept every thing and every situation we meet, whether “favorable” or “convenient” or not, just as it is. It is how to live every moment just as it is. “Every moment is a good moment” only when we live every moment just as it is.

* * * * * * * * * *

Zen is easy to talk about but difficult to practice, especially in our daily lives. If I am asked if I live every moment just as it is, I must honestly answer that I cannot. I just sit zazen every day and give my whole body and mind up to zazen, whether or not I am able to live every moment just as it is.

I came as the resident priest of the Milwaukee Zen Center last September. I have a family like some of you and try to live a Zen life in the same situation as you. I came here not as your teacher but as one of your enthusiastic associates at the head of the parade of practicing. Please excuse me if you feel that I am trying to teach you something. I am also telling myself what I tell you.

Please help me study and practice together with you so we can make 1986 a good year, though it will be a good year anyway, and so the Milwaukee Zen Center will prosper.

Anchorage Zen Community Newsletter 2001 ~ 2005

Death

At Daieiji monastery where I trained, there was an elderly layman called Yat-chan. He was both mentally and physically disabled. He had difficulty speaking and stammered so it was hard to understand him when he spoke. Most likely the abbot of Daieiji allowed Yat-chan to live in the monastery because he could not live by himself. Yat-chan slept on the second floor of the kitchen building, ate alone, and chopped wood from morning till evening every day. He was almost always alone. The novices, with the exception of me and a young novice named Hakuit-san, ignored him or made fun of him. I thought he was mentally disabled from birth, so I was very surprised one evening to see him cheerfully trying to sing an old popular song and dancing when priests and parishioners of the temple had a party and drank a lot of sake and beer. I realized he may have lived the same life as we did when he was young.

One cold evening Hakuit-san and I were sitting in front of a fireplace in the middle of the kitchen. Yat-chan was also sitting with us. Hakuit-san and I were talking about death; we may have had a funeral or a memorial service that day. I asked Yat-chan, “Yat-chan, what age do you want to live till?” He replied, stammering and in a tone difficult to understand, “Well..., until about...eighty years old or so...” “How old are you now?” I asked. “Seventy,” he said. Hakuit-san asked, “You won’t mind dying in ten years, then?” I cannot forget the startled look and the fright in Yat-chan’s face when he heard Hakuit-san’s words.

In Japanese Zen temples they hit a wooden han, a board, after Zen sitting is over. On the han is written, “The matter of birth and death is of great importance. Impermanence is swift.” Birth and death are both important, but people only like birth, not death. They turn their faces away from death. My sister told me that once when her husband and she were talking about purchasing a grave site for themselves because her husband was approaching retirement, their daughter got angry and told them not to talk about such ominous things. I wondered how my niece, a nurse at a nursing home, could say that. Later I found out she had said that because she had been so shocked by the sudden death of my father-her grandfather. But he was ninety-four years old when he “suddenly” died!

To be honest, I did not used to think seriously about death either. Death seemed far away from me until I came to Los Angeles to work as a minister for a Japanese Zen temple, Zenshuji. I do not remember exactly how many funerals we had at Zenshuji, but I probably participated in twenty or thirty every year for over six years. Consequently I saw many bereaved families. Although I was very sorry for them all, some of them impressed me especially. I still remember an elderly man who used to be a leader of the local Japanese community crying at his wife’s death; an old stout-hearted woman who had just lost her only child and was resisting an impulse to cry out; and a girl about seven years old trying to endure the sorrow of losing her mother. Life is sometimes too cruel.

When I saw these people suffering so much, I thought I should face death more seriously. I told my daughter, who was going to elementary school, “Keep in mind at all times that you may die anytime. Also, remember you have many relatives in Japan but you will be an orphan in the United States if your parents die. Please get ready for your parents’ death and don’t be overwhelmed whenever we may die. I know life does not always follow the natural order and you may die before your parents, so your parents will also try not to be overwhelmed whenever you die.” Because I have been telling her this since she was very young, unlike her cousin in Japan she is not allergic to talk about death.

Not only Japanese but Americans, too, do not seem to face death seriously. Many visitors to the Milwaukee Zen Center ask about afterlife or reincarnation but few people ask about death. When I am asked about life after death or reincarnation, I reply as follows:

My first teacher Tosui Ota Roshi often said in the lectures he gave after our weekly sitting, “I want to be born as a Zen monk in my next life, the life after the next, the next life after that, and so on, and to continue to practice Zen sitting.” One day when he was absent, his master, Zenmyo Inoguchi Roshi, gave a lecture. A middle-aged woman asked him, “Ota Roshi often says, ‘I want to be born as a Zen monk in my next life, the life after the next, the next life after that, and so on, and to practice Zen sitting.’ Do Zen monks believe in reincarnation? I thought they didn’t.”

I was shocked by such a pointed question and I waited for Inoguchi Roshi’s reply with breathless suspense. Inoguchi Roshi’s reply amazed me. He said, “We are dying each moment and we are reborn each moment. How can you say, ‘I don’t believe in reincarnation’?”

Inoguchi Roshi was teaching us that we are reincarnating each moment. What’s important is what’s right here right now, so devote yourself to the practice here and now without being concerned about what has not happened yet. However most people do not understand this and pursue the question, “I understand each moment’s reincarnation. What will happen after our breath stops and we completely die?” I answer, “I haven’t died yet so I don’t know. I’ve heard of near-death experiences but I’ve never heard about the experiences of those who really died and never revived. I am looking forward to dying so I myself will know what will happen or not happen.”

Living here and now does not mean not to think about other places and other times. Here and now includes the whole world and the past, present, and future. In order to live here and now to its fullest, we must think about things and people throughout the whole world, learn lessons from past experiences, and prepare for the future.

We meet ups and downs in our lives. I should rather say life is an endless repetition of up and down. We must not be beaten by downs. At the same time we must always prepare mentally and physically for those times of going down. Death is one of the most complete downs. We should think about death seriously and prepare for the death not only of ourselves but of people close to us.

In the end I would like to add one more thing. When I visited Daieiji six years after I talked about death with Yat-chan, he was nowhere to be found. A young priest guided me to his grave. Thinking about him now, I realize that I will be that age in just ten years.

Tozen Akiyama

(This is a revised version of an article in the MZC newsletter.)

Following is not the opening article.

New Year’s Day is the most important holiday in Japan. I would like to share with you an article I read in a Japanese newspaper published in Los Angeles. Please excuse me if my memory is not completely accurate. I read the article several years ago.

A man visited the resident priest of his temple on the New Year’s Day. He said, “Priest, today is the first day of the year and a happy day. Could you write a calligraphy of something happy?”

The priest wrote something on a paper and gave it to him. It was written, “Grandpa dies, grandma dies, dad dies, mum dies, children die, and grandchildren die.”

The man got upset and said, “I asked you to write something happy!” The priest said, “That’s why I wrote a happy thing.” The man said, “It’s not a happy thing at all.” “Why not? Read it,” the priest said. The man read and said, “Grandpa dies, grandma dies, dad dies, mum dies, children die, and grandchildren die. How can it be happy?” “Is there a happier thing than dying in such a natural order as grandpa dies, grandma dies, dad dies, mum dies, children die, and grandchildren die?” The priest replied.

Great Peace and Joy in the Midst of Suffering

My daughter called me recently and said, “My good luck seems to have come to an end.” I asked her, “What happened?” “I had an accident,” she answered. Several years ago, when good things kept happening to her, I told her, “Life shouldn’t be so easy. When you go up, next you will go down. When you go down, then you will go up. Your good time will come to an end someday. Be careful.” She probably remembered my words when her favorite, expensive, and brand-new car was hit by another car, culminating a series of unlucky events.

Since I told her to be careful, I have seen people on every side---close at hand and on TV, by letter and phone, in newspapers and magazines---meeting happiness and unhappiness, joy and sadness, good fortune and bad fortune. Needless to say, I am no exception. While I was seeing and hearing people’s ups and downs, as well as experiencing them myself, I thought to myself that life is really suffering, just as Shakyamuni Buddha said. As I have said for a long time, the Buddhist meaning of suffering is not restricted to unhappiness, sadness, and bad fortune. What we call “happiness,” “joy,” and “good fortune” are also considered suffering.

We are usually elated when our life is on an upswing, and we like to think that condition will continue forever. But nothing in the world is permanent, and to our disappointment our sunny times come to an end. When we are down, we are also inclined to think that condition will last forever, and we may feel not only disappointed but also depressed. When we are in the cellar, we completely forget that there is no other way to go but up. This cycle or endless repetition of happiness and unhappiness, joy and sadness, and good fortune and bad fortune is itself suffering.

Buddhism may be said to be a body of teachings about how to be free from suffering. Some Buddhists think “to be free from suffering” is “to cease suffering.” They interpret the third of the Fourfold Noble Truths, “Nirvana is the state where all sufferings are extinguished,” in a literal way, so they believe that this truth means “to cease suffering completely.” This is why some Buddhists have believed they could enter perfect nirvana only after their death. When I think of myself, people around me, and those suffering worldwide, I cannot help thinking that human beings can never extinguish all the suffering of humanity. Human beings will die out before the arrival of the time when all suffering is extinguished from the world. In fact hoping or waiting for that time to arrive is itself suffering.

Buddhists have to be peaceful without being disturbed by conditions and environments around us, but that does not mean we are like vegetables. Human peace must be dynamic, not static. To live as a Buddhist is not to live by suppressing human thoughts and feelings. Dogen Zenji says in Shobogenzo Genjokoan, “Since the buddha way by nature goes beyond [the dichotomy of] abundance and deficiency, there are arising and perishing, delusion and realization, living beings and buddhas. Therefore flowers fall even though we love them, weeds grow even though we dislike them” (translated by Shohaku Okumura). It is quite natural for human beings to be pleased when their life is up and to be disappointed when their life is down. The point is not to be compelled by these states and their changes. Otherwise our lives will be a disaster. If we are just enraptured because our lives are up, we will get in a panic when we go down. The higher we are, the bigger our confusion will be when things change. We should enjoy a good time but at the same time we should not forget that what is now up is likely to go down someday. While appreciating from the bottom of our heart how it feels to be up, we can prepare mentally and physically for the time of going down. When we go down, we can think about why we are down. These are precious teachings: we can learn much more from unfavorable conditions than from favorable ones, including understanding the pain of other suffering people. That way, we will naturally appreciate being down even though we may also be disappointed.

Impermanence is one of the most basic Buddhist teachings. Life would be boring if there were no up and down. View up and down as the scenery of life and appreciate any situation you are in, whether it is up or down. This is not to cease suffering but to live in great peace and joy in the midst of suffering. “Great peace and joy” is a phrase in Dogen Zenji’s Shobogenzo Zazengi. He says, “Zazen is not learning (step-by-step) meditation. Rather zazen itself is the dharma-gate of great peace and joy (nirvana). It is undefiled practice-enlightenment” (translated by Shohaku Okumura). Our practice is not to gradually decrease delusion and to finally attain enlightenment and enter nirvana. Enlightenment is practice; practice is enlightenment, great peace and joy. “Great peace and joy” are not obtained only after we “attain enlightenment” or “cease suffering.” In Buddhism “great” means “unconditionally great,” that is, it has nothing to do with “before” or “after”; it is not “great” in comparison to “small.” We do not suffer in order to cease suffering, we live in great peace and joy in the midst of suffering. This is “to be free from suffering.” Let us appreciate suffering.

Tozen Akiyama

(This is a revised version of an article in the Milwaukee Zen Center newsletter.)

The Reality of All Existence

One of the most basic teachings of Mahayana Buddhism is the reality of all existence, which was taught in the Lotus Sutra. It means, “All phenomenal things are themselves the ultimate reality.” The term “ultimate reality” may be changed to absolute reality, undeniable fact, suchness, thusness, or as it is. Whatever word is used, it may be difficult for many people to understand its meaning. I sometimes rephrase it as “Everything in the world, visible or invisible, tangible or intangible, is complete as it is here and now.” The meaning of this teaching is not easy to understand, so I would like to try to explain it.

Several years ago when I was trying to find out how I could explain its meaning, my brother sent me a Japanese animation video tape titled, “The Birth of the Earth.” It is the first program in a long science series entitled “The Great Journey of the Earth.” One of my American friends said he saw it when it was aired in the United States so I do not know if the tape is Japanese or American. I think it can help you understand “Everything is complete as it is here and now,” so I translated the Japanese transcript into English.

The Birth of the Earth --- The Great Journey of the Earth

About four billion six hundred million years ago, gases and dust clouds that spread in the boundless universal space started to flow slowly in a swirl. Much of the gas gathered at the center of the swirl, forming the sun, which began to burn. Hot gases around the sun cooled down and formed solid masses, minute planets whose average diameter was about six miles. Numberless minute planets drifted about in the universe of what would become our solar system. The minute planets began to collide with each other, and they either broke into fragments and scattered apart, or combined to form larger planets. After a long time, remarkably large heavenly bodies evolved out of the numberless minute planets. These larger heavenly bodies had greater gravitation, so they grew even more rapidly, by absorbing more minute planets. These maturing heavenly bodies are the original Earth, Mercury, Venus, Mars, and the other planets we know.

At this stage, the just-born Earth was covered with craters from the minute planets’ collisions. Meteoric stones collided at supersonic speed, heated the air, and shone brighter than the sun. At the moment of these supersonic collisions, the planets’ kinetic energy was transformed into heat, causing huge explosions, strong shocks through the Earth, and enormous craters. As this primitive Earth became larger, gravitation increased, so the speed of collision also increased, and the surface of the Earth was melted instantly by the heat produced in the collisions. As this was repeated, the Earth started to be covered with magma, molten rock, which was over two thousand degrees Fahrenheit. The collisions continued, and more heat was stored at the surface of the Earth. The Earth’s whole surface melted, giving birth to the magma ocean, which soon became about three hundred miles deep. The original Earth was changed into a star-like fireball because of the energy of the collisions.

As the hot gases had earlier cooled down and formed the minute planets, water had been locked in, and it evaporated and escaped as the collisions occurred. A large amount of steam rose from the surface of the primitive Earth, covering it with a thick layer of vapor. Above this layer of vapor, the sun’s ultraviolet rays broke down the water extensively, and the hydrogen that was released dissipated into the universe because it was so light. The same process was happening on Venus, which is called the twin of the Earth; but on Venus, which is a little closer to the sun, the water continuously broke down, and Venus became a planet without water. On the Earth, as the number of collisions decreased, and the planet’s growth slowed down, the magma ocean started to cool down. When the surface temperature dropped to about five hundred seventy degrees F., a decisive event separating the destinies of Venus and Earth occurred---it started to rain on Earth. The rain rapidly lowered the temperature on Earth, which in turn invited more rain.

Torrential rain continued constantly. Great floods raged on Earth. Water formed violent streams and waterfalls; ponds became lakes; lakes formed an ocean; and the ocean covered the Earth in an instant---“in an instant” compared with the long history of the Earth until then. This was the beginning of the Earth as an oceanic planet. The oldest stone on Earth, which tells the story of the birth of the ocean, was found in Ias, the southwestern part of Greenland, in 1970. It was found to be three billion eight hundred million years old, which means that the ocean was born on Earth at least that long ago.

The distance from the sun, the presence of so much water, and many other fortunate factors together made the ocean, which in turn caused the mild seasonal changes of the Earth’s climate and led to the splendid evolution of life and to the many creatures on Earth.

Living in the midst of the universe, it is difficult to see how things in the universe come into existence. Fortunately, when I saw this video, I had a chance to see from a vantage point outside of the universe and I thought the video explained the reality of all existence very well.

The first thing I thought of when I saw the tape was that all things and events come into existence as the movement, activity, or function of the universe. When I say, “the movement, activity, or function of the universe,” I do not mean that there exists something substantial that should be called “the universal force,” something that causes movement, activity or function. I just call whatever happens in the universe “the movement, activity, or function of the universe.” Therefore, all things and happenings are themselves the movement, activity, or function of the universe. Also, it has no fixed nature or substantial entity. I was glad to learn later that the famous cosmogonist Stephen Hawking says all matter is the function of the universal wave motion and the entire universe came from this universal motion.

Secondly, there could not be any other way of existence or happening for things and events than how they are, or have happened. It does not mean “inevitable,” as in “fated to happen”; it means “absolute and unalterable” as the present moment, the fact. It does not say it will have to be a certain way in the future. The reality of all existence is only concerned with now.

Thirdly, the movement, activity, or function of the universe, and therefore of all things and happenings, is always just right as it is---neither too much nor too little. Whatever happens is just right in the sense that it simply is. This is not “morally” right, or how it should be; that what happens is just right does not say it is good or bad.

Fourthly, the movement, activity, or function of the universe, and therefore of all things and happenings, never comes to a deadlock, because the universe does not expect to achieve any goal or to move in some particular direction, but just goes on. This movement, activity, or function of the universe is thus always just right, not for some anticipated or desired result, but for the actual result it eventually reaches or the direction it actually goes.

I am sorry that I cannot explain the four points in more detail by giving examples from the tape, because of space limitations, but I think you will understand what I mean if you compare my observations with the text of the tape narration. Also, if you could see the tape with its vivid images, you could understand me better.

From the last sentence of the tape narration, we understand that human beings and our present world would have been created in the same process that shaped the Earth, so the above four principles must apply to current human beings and the world as well.

Among the four principles the second one, “there cannot be any other way of existence and happening for things and events than how they are, or have happened” is the meaning of ultimate or absolute reality, or undeniable fact, in the reality of all existence. Also, the third principle, “the movement, activity, or function of the universe, and therefore of all things and happenings, is always just right as it is---neither too much nor too little,” and the fourth principle, “it never comes to a deadlock but just goes on,” are what I mean when I say, “complete.” In that sense the whole world, including our life, is complete as it is here and now. These three principles are based on the first principle, “all things and events come into existence as the movement, activity, or function of the universe.”

In spite of the famous Zen words “No reliance on words, transmission beyond teachings, imparting the essence of Buddhism beyond written scriptures,” there are so many writings in Zen. However, all these writings and our ancestors are trying to teach us one thing: that our life and the whole world are complete as they are here and now.

Awaken to the fact that life is complete; realize that the world we are living in is complete; so we are living complete life in the complete world. Live complete life with the complete world. This is the most fundamental teaching of Zen.

Tozen Akiyama

Priest in Resident

Freeway Life

I wrote about the Reality of All Existence in our last newsletter. I expressed it in English based on a Buddhist dictionary’s definition as “All phenomenal things are themselves the ultimate reality,” and I said that the term “ultimate reality” may be changed to absolute reality, undeniable fact, suchness, thusness, or as it is. I also rephrased it, “Everything in the world, visible or invisible, tangible or intangible, is complete as it is here and now.” But the words “ultimate,” “absolute,” and “complete” seem to cause difficulty and even to create misunderstanding, so I would like to explore the meaning of the Reality of All Existence again in this issue.

The original Chinese version of this phrase could be translated literally as the True Form of All Existence. In his book From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment, Rev. Tom Daitsu Wright translates “absolute truth” as “undeniable truth” or “inescapable reality.” I wonder if you may understand the Reality of All Existence better if I express it as “undeniable fact” or “inescapable reality.”

When I was working for a Japanese Zen temple in Los Angeles about twenty years ago, I was asked to appear on a Japanese talk show called “Hollywood One Thousand One Night.” It was a live program on Saturday evenings. You can imagine how terrible the traffic is on Saturday evening in LA. I thought I had left my temple early enough to arrive at the TV station in good time, but the freeways were much more crowded than I expected, and I began to be afraid I would be late. When I thought the cars in the next lane were moving even a little bit faster, I would try to invade that lane. When I succeeded, I was happy. When I failed, I was disappointed. On the other hand, when other cars cut in front of me, I was angry and muttered, “I have the right of way. Why is this guy interfering with me?” I lost myself in driving as fast as possible.

I suddenly realized that this is exactly how we tend to run our daily lives. We are always looking around to find a way to satisfy our desires. If we are lucky enough to satisfy them, we feel happy momentarily and then pretty soon we look around again to find ways to satisfy other desires. If we cannot satisfy our desires, we are disappointed and continue to look around. We don’t mind interfering or disturbing others in order to satisfy our own desires, but we get upset immediately if we are interfered with by others. Does driving a car differ from living life?

When I was out driving a few weeks ago, I wondered if driving might be a good analogy for explaining the Reality of All Existence. At that time I was waiting in a turn lane behind some other cars to make a left turn, but the rush hour traffic was very heavy. I said to myself, urging on the other cars in front of me, “Go! Go! Faster! Faster! The signal will turn red soon.” When I was about to hit the accelerator hard the signal changed to yellow and the car in front of me stopped. When I almost hit it I thought, “This is Reality, an undeniable fact!”

When we drive, we have to follow the flow of cars. There are lanes, cross streets, signs, and signals. Roads may go straight, round, up, or down. The city of Anchorage does not take good care of its streets when it snows, so the roads are bumpy here and there and have big pot holes.

We have to be careful not only of road conditions but of our car’s condition. The steering wheel, accelerator, brake, clutch, gas, oil, and water all have to be kept in good condition, and we have to handle them properly. Drivers also have to think of their physical and mental condition as well as those of other passengers, especially children.

These are all undeniable facts. If we ignore any one of them, we are unable to drive correctly. However, if we take good care of our cars, pay attention to road conditions, follow traffic rules, and avoid reckless or unreasonable behavior, driving will be comfortable and enjoyable. Of course, even if our car is in good condition and we follow all the rules, another car or a pedestrian may violate a rule and we may collide. If we are injured or die as the result of an accident, that also becomes an undeniable fact and we cannot escape from its reality. We have to solve the problem without distracting ourselves in vain hopes or dreams.

The Reality of All Existence teaches us to accept whatever happens in our life as an undeniable fact or an inescapable reality but it does not mean to live passively or pessimistically. Just as we do when we drive cars, we should admit undeniable facts and deal with our lives realistically and positively. We cannot always live as we wish. We may have to stop or wait. We may have to turn, go through a bumpy stretch, or make a long detour. But if we accept these circumstances as undeniable facts and cooperate with them, we will each be able to appreciate our life as it is just as we can enjoy driving. This is the teaching of Reality of All Existence.

Tozen Akiyama

Priest in Resident

Cold Is Just Right

The mountains around Anchorage are already covered with snow. The cold, dark, and long winter is close at hand. Before I came to Anchorage in June last year, I was afraid if I would survive the winter in Alaska. Now I am happy to say, “I love the cold.”

I moved to the Milwaukee Zen Center from Zenshuji, the Japanese Zen temple in Los Angeles, in September 1985 and visited Zenshuji in February 1986 in order to participate in a big ceremony. Zenshuji members welcomed me back and said, “It is cold in Milwaukee, isn’t it” I answered, “The temperature is low in Milwaukee but we don’t feel so cold because we have central heating indoors and we wear warm coats when we go out.” Most people didn’t believe me and replied, “Oh, no. You are telling a lie,” or “You must be pretending you don’t mind the cold.”

This happened so many times that the bishop said, “He is trying to convince everyone that Milwaukee is warm,” and I said, “Yes, and everyone is trying to convince me that Milwaukee is cold.” After that I made up my mind to answer, “Yes, Milwaukee is really cold.” Everyone seemed pleased with my new answer.

A few days later a priest arrived from Nagano, Japan, to participate in the ceremony. Nagano is cold and the 1998 Winter Olympics were held there. The priest said, “The Buddha hall of my temple is as cold as a refrigerator since there is no heater there.” Upon hearing it, I laughed and wanted to say, “You see. It’s exactly what I said!” but I said it only to myself because by that time I had given up trying to convince people how warm Milwaukee is. Recently built Japanese houses have a heater-air conditioner in each room and Japanese people have all kinds of overcoats now. However in 1986 few Japanese families had any air conditioning and they usually heated only the living room, with a kerosene stove, and only while they were there. Therefore they felt cold until the living room warmed up when they came home or when they got up in the morning. They also felt cold each time they left the living room. They did not put on such warm coats either as we did in Milwaukee. That was what I wanted to tell people, but they did not listen or try to understand.

Quarrels and fights never stop in the world; they go on at home, in the community, in the nation, and internationally. One of the main reasons for this is that people think their thoughts are the only right ones and they press their opinions on other people without listening to them.

Kosho Uchiyama Roshi says that zazen or Zen sitting is to open the hand of thought, or to let go of thoughts. If we open the hand of thought, we will realize how small and self-centered “my” thoughts are and be more generous to others. But we are inclined in our practice of zazen to attach to our thoughts or even to reinforce them. This kind of zazen satisfies only ourselves, makes us self-righteous, and helps us cause more trouble around us. We must clearly understand the importance of zazen practiced as letting go of thoughts.

I do not blame the people in Los Angeles for not understanding what I said about Milwaukee. I was also doubtful when I received a letter from an American friend who lives in Tokyo. When I wrote her that I was going to move to Milwaukee, she wrote me back that it was much harder for her to adapt to winter in Tokyo even though she grew up in upstate New York, which is much colder than Tokyo. From the trip to Los Angeles I learned how difficult it is to not be attached to our thoughts and to listen to others and how much we need to practice the zazen of letting go of thoughts. That thought becomes stronger especially when I think of the current disastrous situations around the world.

Finally, I would like to share with you a poem that I heard during my visit to Los Angeles that time. The poem was written by a Japanese Shin Buddhist layman who had passed away two years earlier at the age of 94. In the poem he is talking to himself:

You are just right for you.

Your face, your body, first name and last name are all just right for

you.

Your social position, wealth, parents, children, daughter-in-law, even

grandchildren are all just right for you.

Your happiness, unhappiness, joy and sorrow are just right for

you.

Your life that you have been walking through is neither good nor bad.

It has been just right for you.

Whether you go to hell or paradise;

the place where you go is just right for you.

There is no need to think highly of yourself,

but neither think little of yourself.

There is neither above nor below.

Even the time of your passing is just right for you.

How can this life, together with the Buddha, not be just right?

Cold is just right. Darkness is just right. Everything is just right, with the zazen of letting go of thoughts.

Tozen Akiyama

Priest in Residence

(This is a revised version of an article in the Milwaukee Zen Center newsletter.)

True Religion

In my 2002 year-end greeting I wrote, "This has been a year of decadent conditions that seem like a feverish fin-de-siecle, more like the end of a century than the beginning of one." As many people have suggested, people do not seem to learn from history. We human beings continue to create the same kind of troubles and to kill each other. I am especially sorry that many people and groups make use of the word "religion" to justify harming people who disagree with them. Religion should never be made use of to make people suffer, but only to free them from suffering.

On the first day of my Zen Sitting class at the University of Alaska Anchorage I tell my students the following:

There isn't one single true religious teaching for the whole world. This teaching may be true for some people but not for other people. That teaching may be true for some other people, but again not for all other people, and so on.

However the character of religion is such that there can be a single true teaching for MYSELF. It is important to find the teaching that is absolutely true for myself. But it does not mean other teachings are absolutely wrong. We should accept that other teachings may be absolutely right for other people.

We should not fear or hate our differences. Because we are different we can find something new, and learn. We can learn more from differences than from similarities. What we should be afraid of is not differences but intolerance. Not only should we be tolerant and generous to different teachings rather than denying or rejecting them, but we should appreciate them for offering us something to learn.

We do not all have to agree or reach one conclusion in class, and I do not intend to convert you. I just wish for each one of us to learn and to deepen and strengthen our understanding and faith from this class.

It is quite natural that we look for a single true teaching when we start searching for the meaning of life. When we find, or we think we have found, the true teaching, it is important to have faith in it, but then it is very difficult to see other perspectives. Too much is as bad as too little. When our faith is too strong, we are inclined to insist on the righteousness of our religion or even to force our beliefs on others. As a result we argue, fight, or even kill those who do not agree with us. Religion should make people happy, but this kind of action only brings about tragedy in the name of religion.

On the other hand, I sometimes hear people say our religions are different but they are all about ways of climbing the same mountain. I do not think this kind of statement has any meaning beyond the basic affirmation that we are all human. Certainly we are all humans, but each one of us is a different human; we are not the same. We have to see both sides of equality and difference. We should not emphasize only the ways that things are the same.

When I hear people say it is all one mountain with one peak at the top, they seem to be saying that differences are wrong. What's wrong if we are different? Life would be so boring if we were all the same. Also we can learn from others because they differ from us. We should appreciate the fact that we are all different. Most religions may be said to try to achieve human happiness, but what they conceive of as happiness is very different.

All mountains are mountains, but they are all different mountains. Their shapes and heights, the trees and grasses that grow on them, and the animals that live on them are all different. Why do we all have to climb the same mountain?

Even if the top were the same, there would be so many different routes to reach it. It is especially important in religion to have different routes. We should appreciate and enjoy these many routes.

Sister Janet Petersen, a Catholic nun, was the vice-president of the Milwaukee Zen Center. She understood Zen very well. When other members were struggling with my words, "Zen has no merit," she said with a big smile, "Zen has merit called 'no merit.'" When I asked her, "Are there any similarities between Zen and Catholicism?" She said, "Oh, yes. There are many similarities." "What about differences, then?" "There are also differences, but the biggest difference is God. You say there is no God in Zen, but the more I sit, the closer I feel God is." I never forget Janet's constant smile, I appreciate her deep understanding of Zen, and I respect her firm faith in Catholicism.

We do not have to climb the same mountain or take the same route. If we really understand our own religion, we will have firm faith in it and still accept and learn from different teachings as well as similar ones. Then we can live in peace and harmony with the whole world. This is what true religion is for me.

Tozen Akiyama

Priest in Residence

Honesty Not Modesty

March 30th is the evening of the Academy Awards for 1991. I wonder whether it is because I've grown too old that I do not feel as drawn to recent movies as to old ones. I am too busy to see movies anyway.

On the evening of the Academy Awards in 1990, an internationally famous Japanese film director, Akira Kurosawa, who is called "Emperor Kurosawa" in the Japanese film world, received the Oscar Special Honorary Award. According to a Japanese newspaper published in Los Angeles, an audience of over three thousand gave a standing ovation when two American directors, Steven Spielburg and George Lucas, who respect Kurosawa as their teacher, introduced him and he proceeded to the stage. The paper also said that Japanese people, possessed by an inferiority complex about their short statures, must have been pleased to see Kurosawa taller and larger than the two American directors. The "emperor" said slowly in Japanese, as if he were digesting the joy, "I feel it a great honor to receive such a splendid award. However, I am a little concerned about whether I deserve this award because I do not understand film well yet." When an interpreter translated it into English, sighs of praise were heard. He added, "Movies are wonderful. It is difficult to catch a wonderful, beautiful thing. I will continue to do my best to catch a wonderful thing called a movie in the future." He became eighty years old three days before.

A Japanese woman married to an American man challenged Kurowasa in the newspaper saying that his speech merely exhibited the Japanese style of modesty in contrast to other winners who honestly expressed their joy at receiving the awards and appreciation to their staff and families who contributed to their awards. Too much modesty becomes servility. The Japanese must keep in mind that in American society it is not only that modesty does not pass as a virtue but that it is understood as lack of confidence. It might also seem to impugn the ability of those giving the award, to think meanly of oneself who receives the award.

Another Japanese woman who has an American husband replied to her. She is the makeup assistant for an actress working then in a film directed by Oliver Stone, who received the award for the director of the year. They were celebrating in the studio the next day. After thanking people who congratulated him, Mr. Stone said that even Kurosawa had said he did not understand movies well yet and so he could not be self-complacent, either. There was no guarantee that the film he was making would go well even though he had received one or two Academy Awards. Everybody agreed. Her associates in the makeup department said that because Mr. Kurosawa said these words, they impressed people. She was smiling the whole day as if one of her relatives had been praised. Mr. Kurosawa probably was dissatisfied each time he made a movie. This is what he was expressing. She does not think Kurosawa's words were modest: she thinks they were his real thought.

There are other stories of this kind. Hokusai is one of the greatest Hanga (Japanese wood-print) painters. At his bed of death, "Reaching out his hand to Chin-chin (his daughter) he cried in anguish: `If Heaven would grant me ten more years!' Then, grasping for breath he cried again: `If Heaven would grant me five more years, I would become a real painter!' A few hours later Hokusai was dead." (HOKUSAI A Biography by Elizabeth Ripley, J. B. Lippincott Company) Michelangelo was full of enthusiasm about working even when he was eighty-eight. He uttered at the last moment of his life: "I just started understanding the ABC of work. I want to work more." I do not think they said these words because of modesty. As the makeup assistant thought, the words must have come from the bottom of their hearts.

Some people say that I am a humble person. It may be because I say, "I am hopeless," or "The more I practice Zen, the more I realize I am compelled by empty comings and goings of thought." Other people say it is my way of talk. They are not right. Even artists know themselves. Why can religious practitioners also not realize themselves?

I am neither a humble person nor trying to be eccentric. I am talking of the reality of myself and human beings. As I always tell you, we must not be drunk with beautiful words or ideas. Zen must be based on our own lives. I introduced you to Sawaki Roshi's words in our newsletter (Vol. 4, No. 2): "The more sober we become, the more clearly we see that we are no good." I interpret "no good" as "being compelled by empty comings and goings of thought." As long as we human beings live with the brain, we cannot stop thinking and we cannot help being compelled by thoughts. This is why I say I am hopeless. We must realize this reality of human beings.

If we overlook or disregard this reality, Zen is just the playing with beautiful words. If we are disappointed with it and stop practicing, however, we do not understand Zen, either. We should realize the emptiness of our thoughts each time we are compelled by thoughts and continue to practice. We do not attain an ideal condition called enlightenment as a result of practice. We continue to practice until the last moment of our lives, led and guided by the realization of emptiness. This is what is called "oneness of practice and realization." Let us remember Dogen Zenji's words which I also quoted in our newsletter (Vol. 5, No. 2): "Before one has studied the Teaching fully in body and mind, one feels one is already sufficient in the Teaching. If the body and mind are replete with the Teaching, in one respect one senses insufficiency." (Shobogenzo Genjokoan)

Tozen Akiyama

Priest in Residence

(This is a reprint of an article in the Milwaukee Zen Center newsletter.)

Just Sit!

Zen sitting of our Soto Zen Buddhism is called shikantaza or just sitting. Some people say faith is important in order to practice shikantaza, but this is meaningless to me. We have to have faith in whatever it is we practice. In addition, faith without correct understanding is blind faith, which is very dangerous. We see many examples of that kind of faith. We have to understand shikantaza correctly in order to have faith in it. I would like to explain what shikantaza is in this article so we can have correct, open-eyed faith in it.

When I did not know anything about Zen but wanted to learn it and visited the late Tosui Ohta Roshi for the first time, he said, slapping his shaved head, "What's wrong is 'this guy.' Chop off from here (pointing to his neck), put it here (pointing beside him), and sit. That's all." I thought, "It is exactly as he says. This is the path I have been looking for." I have never doubted his words and have been practicing 'chopping off this guy' ever since then.

Everything in the world exists here and now. Mountains, rivers, plants, and animals, they all exist as they are here and now. There is nothing in the world that does not exist here and now. Am I right? ― Wrong!

If everything existed here and now, there would be no suffering in the world. But the fact is the world is full of suffering. We suffer because there is something that does not exist here and now. What is it? The contents of our thoughts!

Our brain always exists here and now, and it constantly creates thoughts, as naturally as any body secretion. But the contents of these secretions called thoughts are rarely here and now, which means we are almost always thinking of the past or future in some other place. If our thought were only here and now, we would accept the reality of any condition we were in and live through it. When our thought is not here and now, however, we think conditions somewhere else are better than what we face here and now. We chase after conditions we think are better and try to escape from conditions we think are worse. By trying to satisfy our desires like this, human beings have developed the wonderful civilization that we now enjoy.

At the very same time, people have created so many kinds of suffering. Our desires are one thing and the activity of the universe is another. The world does not always go as we wish, and at those times we suffer. If we are fortunate and the world goes as we wish, we will continue to try to satisfy our desires until eventually the time comes when the world no longer goes as we wish. If we were so lucky that the world went as we wished permanently, we would be just bored.

Our brain is the source of suffering. That is why Ohta Roshi said, "What's wrong is this guy." But we should not misunderstand this and think that our brain and thought are fundamentally wrong. To say so is the same as saying our heart and lungs are fundamentally wrong, since they are the source of heart and lung diseases. The brain is an indispensable organ for human beings just as the heart and lungs are. Also, thinking is a natural function of our brain, just as blood circulation and breathing are natural functions of heart and lungs. Do you ever think we should stop blood circulation or breathing because it can lead to diseases? Of course not, yet surprisingly many people think our zazen practice is to stop thinking.

"Chopping off our head" does not mean to stop thinking but to have both our body and mind here and now. Thoughts are constantly coming up in our brain. If we catch them, they take us to some other time and place. If we chop off our head, we do not latch onto any thought. Any thought that does not get caught up in our brain just naturally goes away. Therefore Kosho Uchiyama Roshi calls it "opening the hand of thought." If we open the hand of thought, we do not hold on to any thought, so we will not be carried away to any other place or time. I have heard that some American people prefer the expression "letting go of thought" to "opening the hand of thought."

Recently a newly edited version of Opening the Hand of Thought by Uchiyama Roshi was published by Wisdom Publications. It is such a good book that I would like to recommend it to everybody. In that book Uchiyama Roshi explains in detail about what actually happens in our brain while we are just sitting, doing shikantaza. He says if we think or sleep while sitting, we are thinking or sleeping and not practicing just sitting. Later he restates this and says thinking and sleeping are the reality of life and so they are the reality of zazen, and as long as we live we cannot eliminate them from our sitting. Shikantaza is not only the condition of just sitting but the repetition of just sitting, thinking, sleeping, and returning to just sitting.

Ohta Roshi used to say shikantaza is the simplest and easiest practice. I have been enjoying, appreciating, and teaching such a simple and easy practice since I came to the US. But I am surprised many American practitioners say shikantaza is very difficult to understand and practice.

When I ask them why shikantaza is so difficult, they answer, "I cannot chop off my head," or "It is very difficult to open the hand of thought." They seem to think they are practicing shikantaza only at a moment when they are completely chopping off their head or opening the hand of thought, in other words, not thinking. This is the same as saying shikantaza is to stop thinking and they are confused when I deny that shikantaza is to stop thinking. I tell them, "Just sit, whether you think you have succeeded in chopping off your head or opening the hand of thought. Just sit without being concerned whether you think or not or how you feel. That is shikantaza." I tell them how one of Uchiyama Roshi's disciples and my teacher, Rev. Shojo Karako, describes it. He says, "Opening the hand of thought is neither a psychological technique nor a process only of letting go of thoughts. It is not only a mental activity but the activity of the whole body and mind." I have been repeating this over and over and over again but people still seem to have difficulty understanding it. My explanation or definition of shikantaza may not fall within their idea of what Zen sitting is or should be.

While wondering how I could explain it better, I recently found a very good explanation of shikantaza by another disciple of Uchiyama Roshi, Rev. Shohaku Okumura. He says in Shikantaza, published by Sotoshu Shumucho, "Uchiyama Roshi often compared sitting zazen to driving a car. When we drive, it is dangerous to sleep or to be caught up in thinking. It is also dangerous to concentrate one's mind on an object like the brake pedal, the gas pedal, or the steering wheel. We concentrate our entire body and mind on the whole process of driving a car. Our sitting is the same. We don't set our mind on any particular object, visualization, mantra, or even our breath itself. When we just sit, our mind is nowhere and everywhere. Then we can say that our body and mind is concentrated in just sitting."

I have nothing more to add. Wholeheartedly sit without your mind set on any particular object and without concern for whether you think or not, or how you feel. Don't be concerned about whether you have succeeded in it or not. THIS EFFORT ITSELF, to have our mind nowhere but everywhere, is shikantaza. This is to have both our body and mind here and now.

Do you understand now? If yes, congratulations! If not, I have no more words to say, at least for the moment.

Tozen Akiyama

Priest in Residence

Contentment and Acceptance

Zazen is the most fundamental practice of Zen but we cannot practice zazen twenty-four hours a day. We have to do many things every day, making zazen part of our daily life. This is a complex topic, and I want to focus here on just one aspect of it: even though we do not practice zazen twenty-four hours a day, zazen has to lead our whole twenty-four-hours-a-day life. Practicing Zen is to live a life led and guided by zazen.

How can we live a life led and guided by zazen? We usually live controlled by our brain. Our brain dreams of an ideal condition and thinks how wonderful it will be if that condition is realized. Our brain is not satisfied unless the condition it calls "good" is realized. But the world does not move for the sake of our favor or convenience. Our wish is one thing and the movement of the universe is another. Our wish is our egoistic desire that separates us from the world. We mostly struggle in vain to accomplish our wish, but if we are lucky, our wish may be realized. Then we inevitably create another wish and chase after it --- there is no end to this process.

The more our desires are satisfied, the more we want. The more favorable or comfortable our lives become, the more favor or comfort we want. By continuously trying to satisfy our desires, human beings have created such wonderful civilizations as we now enjoy. At the same time we have created the enormous suffering we have now.

Only when we let go of our ideas of perfect conditions modeled for our favor or convenience, and are content with whatever condition we are in, are we completely free from struggle. This is to live a life led and guided by zazen, in which we open the hand of thought, not grasping at ideals and desires. This is why the Buddha taught contentment before he died. In The Sutra of the Last Teaching of the Buddha he says:

If you want to be free from all suffering, you must practice contentment. The dharma of contentment is nothing other than the place of richness and joy, peace and tranquility. A person of contentment, even if he or she lies on the bare ground, is peaceful and joyful. A person of discontent, even though he or she dwelt in the palace of heaven, would not be content. A discontented person, even if he or she is rich, is poor. A person of contentment, even if he or she is poor, is rich. A person of discontent is always pushed around by the five desires and is pitied by a person of contentment.

When we are content in any situation we are in, we accept our conditions as they are and do not continue to seek a perfection shaped for our favor or convenience, and thus we are free from struggle. Some people say that we should not accept things as they are, and they point out the tremendous problems in the world, like injustice, hunger, war, pollution, natural disasters, and so on.

It is certainly not right in the eyes of Zen to accept and just be content with ourselves, leaving those wrong conditions as they are. Zen is not an excuse for ignoring problems. Zen has been made use of, whether intentionally or unintentionally, to bolster established authority. Zen Buddhists have sometimes even cooperated in wars under the guise of being egoless or without attachment, as described in Zen at War by Brian Victoria.

By “accepting how we are” I do not mean to accept all conditions as morally right or to shelve judgment. I mean to accept conditions as undeniable facts or inescapable realities. That is, there is no other way of existence right now than how we are here and now, and we cannot escape it at this moment. Of course we should make efforts to solve problems, and we should not accept the misuse of power. Acceptance does not mean that what is wrong should not be reformed or changed. However, if we do not accept that conditions area as they are, that they are undeniable facts or inescapable realities, we will continue to judge conditions in terms of our favor or convenience and our wish to change them will be a matter of satisfying our egoistic desires.

How do we know when we should be just content and continue to live as we are, and when we should try to change our conditions and solve problems while also remaining content? We have to be content in ANY condition we are in and accept that condition as an undeniable fact or inescapable reality. Only then we will be able to judge correctly whether we should change conditions and work to solve the problems we face, or we should settle down because we are just causing problems misguided and driven by our personal favor and convenience. In the latter situation we must stop trying to change conditions, since it is nothing but trying to satisfy our egoistic desires. If we really want to solve problems, we must try to find out how to change or end them not by satisfying our egoistic desires that separate us from the world but by cooperating with the world. The true face of this cooperation is empathy, love, kindness, appreciation, and gratitude.

I wrote two articles on this topic in the Milwaukee Zen Center newsletter. I made them into one article this time so it may sound abstract and lacking in concrete examples, but I hope you will understand what I want to say.

Tozen Akiyama

Priest in Resident

The Reality of Hopeless Humanity

Life led and guided by zazen is contentment and acceptance, so I practiced just sitting with great seriousness and lived every day with contentment and acceptance. I thought, “I am perfectly content in my life. I have enough food and drink, clothing, a roof over my head, a car that runs, money, a job, and so on - there is nothing more I want.” I thought I was one of the most contented and least greedy people in the world.

At some point I said to one of my disciples, “I think there’s something wrong with my life.”

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

I answered, “My life is so easy lately. I have no problems. Life shouldn't be so easy.” “Be patient," she said, "you’ll have problems soon enough.”

She was right! Soon after that I thought again, “There’s something wrong with my life,” but in a different way this time. I realized I was far from contentment and acceptance. I noticed that I argued and quarreled with my wife and daughter almost every day. That means I was not content with and accepting them as they were but wanted to control them. All my food and drink were so delicious that I ate too much every day. I wanted to nap in the car even if only for a minute before an appointment, because I was too busy to sleep enough at night. My family could afford only a cheap old car, so I wanted a better car whenever our car had trouble, which happened often, especially in cold weather. The building of the Milwaukee Zen Center was a hundred years old so the kitchen sink was regularly clogged and water overflowed, the shower didn't have enough hot water, and the water heater sometimes stopped working, even on Thanksgiving Day. Each time I had trouble, I wanted to live in a house with better plumbing.

I sometimes found myself hurting the feelings of others and upsetting them. I tried not to hurt or upset people, I always wanted to be good to them, but I hurt and upset them carelessly, unintentionally, or even with my good will. It was so painful to see them hurt. And by hurting others, I hurt myself, too.

I was so disappointed when I realized I was just living a life of self-satisfaction and self-deception. I fell into self-abhorrence and it seemed to me that I had been practicing in vain all those years. I practiced zazen harder, but no matter how hard I practiced, I could not change my life. I was carried away by thought and caught up in a conflict between anger and joy, love and hate, contentment and discontent, and so on. I thought I was hopeless. I was so disappointed, even desperate, and I started thinking I should stop being a priest.

One day, however, after I had been struggling and wearing myself out for quite a while, I saw that being compelled by thought is just how we human beings are. It is neither good nor bad, it is simply the reality of human existence. I remembered that my high-school textbook of history had said, “The origin of humanity lay in walking erect and using tools, fire, and language.”

Language and thinking have probably always worked hand in hand, from their very beginning creating desires that have been the driving force of human civilization as well as of suffering. Thinking and trying to satisfy desires thus have always been intrinsic characteristics of human beings. Those who do not think and try to satisfy their desires are hardly functioning as human beings.

Human beings cannot live without brains, which cause thinking. As long as we live with thinking, we cannot help living in a dualistic world where there is good or bad, right or wrong, peace or anxiety, joy or sorrow. We naturally want one and reject the other. To be compelled by our desires is the karma not only of individuals but of all humanity. It has been with us since our birth as a species. Desire has not been eliminated in all the generations that have passed since the birth of humanity. Since the birth of the human species, through our ancestors and our own life since we were born, we have been creating, accumulating, and living out the results of karma. How can we expect to change or get rid of all that karma in only thirty, forty, or fifty years of practice or even one short lifetime? In Buddhist legends, Shakyamuni Buddha is said to have practiced for three asamkya, or immeasurable, kalpas before he became a buddha, an awakened one. This story is just a symbol of this strong karma of human beings.

When I realized this, I was so relieved and pleased. At the same time, I could not help appreciating the fact that I was hopeless. What I mean is I could not help appreciating my whole life, including hopelessness and the mistakes I make. They brought me to Zen and they made me awaken to the reality of myself and all human beings. This is absolute or unconditional appreciation, not gratitude for receiving benefit or merit, but appreciating the value of receiving anything, beneficial or not, favorable or not, as it is.

We cannot help being compelled by the empty comings and goings of thought, including delusion and desires, in our daily lives just as we cannot help being compelled by the empty comings and goings of thought while sitting zazen. This is the reality of our lives. If we overlook or disregard this reality of our lives, it is just playing with empty, beautiful words or ideas, and we are drunk on ignorance and arrogance. On the other hand, if we only see the compulsive reality of our lives and are depressed, we do not understand Zen, either.

The more I practiced, the more I realized I was such a hopeless person. And then I read in a book written by Uchiyama Roshi something like the following (I am sorry, but I do not remember exactly) that the zazen he practiced when he first started and the zazen he was practicing thirty or forty years later were essentially the same; there was no improvement. He realized that people would be disappointed to hear that, so he pointed out one difference. The difference, he said, is that the more he practices, the stronger his faith gets that he is going the right way.

Indeed Uchiyama Roshi is a great Zen master. Since reading his words, I have refined my expression of my practice to “The more I practice, the stronger my faith becomes that I am going the right way with the realization that I am such a hopeless person."

Again and again, I am compelled by delusion and unable to be content with and accept things as they are. When I realize it, I drop it, remember contentment and acceptance, and swear within myself I will not make such a mistake again. Soon after that I make another mistake. I realize it and vow again. I cannot help walking out of the right path of contentment and acceptance in everyday life just as I cannot help thinking or sleeping when I just sit. But each time I realize it, I return to the right path. It is not that I bring myself back, it is that I am pulled back by realization.

The more I sit, the stronger my faith becomes that I am going the right way with the realization that I am so hopeless. I am content with and accept my hopelessness with heartfelt appreciation.

Tozen Akiyama

(This article is based on several articles that appeared in the Milwaukee Zen Center newsletter.)

| home | What's New Contact DC [It's a little hard - persevere] | Contests | Digressions | Miscellany | table of contents | Shunryu Suzuki | LibraryofTibetanWorks&Archives |

What Was New from 1999 on.