cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

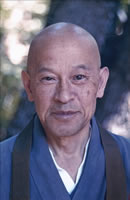

Crooked Cucumber -- Magatta Kyuri -- Hoitsu Suzuki

|

Hoitsu Suzuki’s

Introduction to Magatta Kyuri translated by Fred Harriman

There are books on the history of the World, and

there are national histories written about countries. And tales of temples and

of their origins have also been left to us. It is natural to want to know about

the considerable number of people who have had an impact on our world — their

character and their humanity. At first, when Crooked Cucumber was

completed and a copy was sent to me, I was unfortunately unable to comprehend

its contents because it was written in English. Some years after its

publication, a few members of the Takakusayama gathering came to visit me at

Rinsoin. Among them was Mr. Sadayoshi Asaoka, who upon seeing the newly issued

book immediately sat down to read a few pages and then said with a sparkle in

his eye: “I really want to translate this — it’s so interesting.” I responded:

“Oh please do! I would love it if you were to do that for us.” A few months

later Mr. Asaoka’s translation of the book arrived. I read it while revising

according to the standard kanji characters and terminology used in Buddhism, and

was able for the first time to relate to the book’s contents. Stanford University Professor Carl Bielefeldt in the

United States was the first to attempt to depict a personal history and

biography of Shunryu Suzuki, but his work seems to have been premature in

various aspects, and it did not reach completion.* Yet David Chadwick would step

up, and having understood the manifold wishes and hopes of Americans, he took on

this project, and overcoming many difficulties he began work on what would

become Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Teachings of Shunryu Suzuki in its

original English Edition and later on in this edition translated into Japanese.

I am certain that in that path to publication he faced problems that were not to

be expected. In particular, I refer to Shunryu’s itinerant days in Japan and his

complicated personal relationships. In order to research these comprehensively

David traveled to Japan repeatedly, and he probably had to make repeated

inquiries in this process. I must take this opportunity to express my respect

for his efforts and his persistence. David’s research described a profile of Shunryu

Suzuki that even I as his son and his student did not know about. It was an

unexpected surprise. Shunryu rarely attempted to talk to his children about his

own past. I cannot say why, but probably, if he were to talk to us about the

likely complicated life when he was younger… maybe he thought that the right

timing was needed for us to understand things… or maybe he just didn’t know what

subject to start with. In any event, Shunryu, my father and my master, was not

known to me in any great detail. While I read the translation, the effect of the

book was to bring my father Shunryu before my very eyes as he hustled about here

and there. I was able to meet Shunryu as a young monk, energetically attending

to his projects. In 1958, two years before my father left for the

United States, we took a train on the Tokaido Line to go to Tokyo for my

entrance exam to enter Komazawa University. On the way, somewhere as we passed

through Hiratsuka, he suddenly murmured: “I was born on the other side of that

mountain.” I think I just mumbled something like “Oh…” He didn’t say anything

more than that, and I didn’t make any effort to ask about it either. I simply

wondered what my father’s childhood days were like, and thought that he was

probably musing about all of the ups and downs of that time in his life. And

even after he left for America, he spoke little of any sort of difficulties or

problems he may have been facing at the time – much less about any successes

that he may have been having. He would say simply: “Americans understand and

practice Zen well, even better than Japanese do.” And now, as his student, I am happy to be able to

learn more about my father thanks to the publication of the Japanese Edition of

Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Zen Teachings of Shunryu Suzuki.

Furthermore, the book provides not simply a personal history and biography, but

it also serves as a collection of sayings thanks to David’s clever style and

organization of the book. Shunryu Suzuki’s existence as a person who practiced

and taught about Zen may be talked about in the future. And he may be completely

forgotten by all. But I think that he himself did not concern himself at all

with such outcomes. The only thing he was concerned about was whether the path

of Harmony and Stillness that is Zen will be spread far and wide among the

peoples of the World. As of this writing, twenty years have passed since

the publishing of the English Edition of Crooked Cucumber, and it will

soon be fifty years since the death of our master Shunryu. A Japanese Edition

has now been published and I would like to take this opportunity to express my

appreciation for the efforts of those who were involved in making this possible.

Thank you Kaoru Aragane and Eisaku Kawashima of Samga Co., Ltd. Their efforts in taking over the dedicated work of

Sadayoshi Asaoka in translating the book deserves my sincere respect. With deep humility, Hoitsu Suzuki Disciple and Eldest Son of Shunryu Suzuki and Chief

Priest of Rinsoin *About Hoitsu Suzuki's Introductory Words for Magatta Kyuri, the Japanese edition of Crooked Cucumber - which was featured Saturday Jan. 2. In it he wrote in Japanese: Stanford University Professor Carl Bielefeldt in the United States was the first to attempt to depict a personal history and biography of Shunryu Suzuki, but his work seems to have been premature in various aspects, and it did not reach completion. Nope. I checked with Carl and, as I thought, Hoitsu was thinking about the interviews that Carl, his wife Fumiko, and Peter and Jane Schneider did following Shunryu Suzuki's death. Actually some were done before he died with his visiting family and temple godfather at the City Center. Later in Japan more interviews were done with family and with Noiri, a teacher who revered Shunryu and whom Shunryu greatly respected. Noiri maybe assumed they were doing research for a biography because he talked about how to do a biography of a Zen teacher. So reading what Hoitsu wrote, it looks like he too was thinking they were doing research for a biography. Actually, Peter Schneider had talked some about that. He did the 1969 interviews with Suzuki about his life and encouraged Suzuki to speak to us in a lecture about it. And Peter did other historical research and writing that was reflected in the Wind Bells. When I was working on Crooked Cucumber he mailed me his tapes from Japan. Thanks Peter! Some were damaged in the mail and the tape had to be mounted into new cassettes - but they were all audible. Except for Peter's 1969 interviews with Suzuki, this audio is not on cuke.com. If I ever get back to the US I'll have all the other interview tapes digitized - if they haven't deteriorated too much. But they've all been transcribed and translated. Anyway, all of these interviews were extremely helpful in doing Crooked Cucumber and all can be found now on cuke.com on the Interview lndex page. I appreciate the kind words that Hoitsu said about me and the research done in Japan and I think the conclusion is correct if the credit goes to a team of us, as it wasn't just me. It was a number of us who did interviews in the mid 1990s. All are given credit in the Sources part of the End Matter for Crooked Cucumber though. - dc |