Interview with Nanao Sakaki, poet and godfather of Japanese Hippies

by DC in Minami Izu (Southern Izu Peninsula), Japan, 1/16/04

--------

to interviews

Japan Stories

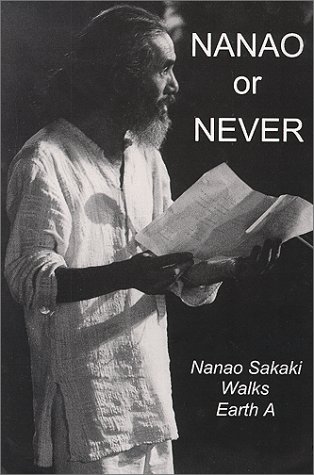

See photo of Nanao at end of interview

Finding the Conch - the Japan story leading up to this story.

Here and Nanao

"O Jama shimasu," I apologized for being a bother, a standard expression one says when visiting in Japan. It's a little more literally true when one shows up unannounced to visit someone you haven't seen in more than a decade and who may not remember you standing there inside their home with a backpack and nowhere else to go. "Surprise," I said meekly.

"Good! good!" Nanao said in English, "I like surprises! Nothing happens here so we very much appreciate your bringing us a great surprise!" He uses a lot of exclamation marks when he talks which I'll omit as I find their excessive use on paper to be irritating.

Kenji stood by the door, letting me take care of myself. I announced my name to remind Nanao. I hoped he would remember it, but I knew he'd welcome anyone who walked through the door.

He repeated my name a few times with emphasis and throwing his head back as if to reminisce, "Yes, yes, a great Zen man comes to visit. You must stay and talk and drink." He looked pretty spry for eighty-one – that’s what Hiro and Nado had said his age was. A long-haired young man came down the packed dirt-floored hall and greeted Kenji and was introduced to me as Nakagawa-san. He got out four cups but Kenji begged out. I thanked him for his kindness, something I'd be doing a lot of for the next two weeks, and he was off.

Nanao asked how long had it been and I said I thought that the last time we'd met was at his trailer in the pine woods of Arroyo Seco, a hamlet at 9000 feet on the side of a mountain above Taos, New Mexico. That was more than twenty years past. I was on a late morning walk coming back from waterfall viewing with a long-red bearded friend from the early Tassajara days named Bob who worked at Dwayne Hopper's Western art gallery called the Buffalo Dancer and with Dwayne's brother who owned another gallery in Taos. I reminded Nanao he’d served the three of us green tea on a stump table with stump chairs and when I’d asked him what he was doing up there he’d said dramatically, "Some days I go to deep mountain to chant Buddhist sutra. Sometimes I visit peyote road man. Some days I wander around like a stupid fool."

"Do you still go to deep mountain to chant Buddhist sutra?" I asked noting his sinewy frame. He looked as if he’d still be hard to keep up with.

"Sometimes walk up hillside behind us," he said. "Always I'm a stupid fool."

We went behind a curtain to a former pig sty now with a wooden floor, wall hangings, a large low table, and an iron stove in front of which they insisted I take a cushion – the honored position. The warmth of the stove did a good job in countering the cold gusts that I assumed blew in only through openings between the boards on the wall - until I noticed later when I went outside to pee that there were rather large openings in the walls of some sections on the opposite side of the hallway – large enough for say, a pig to get through. I said it was sort of like the barn I'd moved into back home but even funkier. "We are barn people," said Nanao.

"How's Ryuho doing," he asked?

Ah, hippie monk Ryuho Yamada. I shook my head and said, "Oh, he has had cancer for some years now."

"Oh, that's too bad. What type?"

"Colon," I said. He didn't understand and I didn't know the word in Japanese so I said, "shiri" patting my butt. Nanao nodded and sighed.

I said that Clay and I had visited with Ryuho and his wife Mayumi in Berkeley the night before we left on our trip to Texas back in July. People were always taking care of Ryuho and for some reason they were ensconsed in a wonderful old redwood mansion in the hills. I'd thought he was in Carmel near Tassajara and intended to visit after our annual ten days stint as students at Tassajara, but there I learned he was back in the Bay Area so we drove back up to see him before continuing down south. I suspected this was my last chance to see him. And Clay's. Clay had met him before and found him intriguing. Ryuho was weak and thin, but in good spirits and had lived much longer than anyone expected, the result, he said, of all the years of physical and medicinal therapy and attention to diet. I told Nanao he was probably not with us any more though I hadn't received any word in emails. Nanao, Ryuho, and I had spent some time together in walking around San Francisco and we made vague comments about that.

There was shochu again and Nakagawa made us brown rice and vegetables which we ate with chopsticks he’d made from local wood. And Nanao and I talked about other people we'd known, including all those from the night before with Hiro.

Nanao asked if I ever saw his best American friend, Gary Snyder, and I said that we'd said hello when we bumped into each other and had spoken on the phone a few times over the years when I had some question he could answer about early California Zen history, but that was all. Nanao said Snyder had visited him the year before but that they’d taken no long hikes as they once did in the mountainous wilderness of California and Alaska. He asked about Richard Baker and I said he was teaching in his monastery in Crestone Colorado and in Germany about half and half, still going strong despite some health problems, and married to a young German princess.

"Oh, Baker Roshi married into royalty?" he asked.

"More like she married out of it."

"And how is Ryuho," he asked? It had been twenty minutes since we'd talked about that and we'd been drinking a little bit and I guessed it had slipped his mind.

"He has cancer, " I said. "He's had it a number of years."

"What type of cancer?" he said concerned.

"Shiri," I said, patting my butt.

After this had happened a few more times, Nakagawa looked up at Nanao and told him it was the fifth time we'd gone over this. Nanao wasn't fazed. "Kenbosho," he said. "I have kenbosho." I asked if that meant senility or Alzheimer's and he wasn't exactly sure. But he was quite cheerful about it.

"Ah, kenbosho is very good," he said. "No need to remember anything anyway. My mind is becoming more empty and free every day! This is a very good thing. I like kenbosho very much."

Nakagawa's comment did seem to work though because Nanao didn't ask about Ryuho again.

"Can you remember things further back pretty well," I asked?

"Little by little I forget everything, but I remember too much still."

"Well then," I said, "How about telling me the story of your life and let’s see how much you can remember. I interview people for the oral history of the early Zen Center times when Suzuki Roshi was alive. I don't have a tape recorder and I don't want to take notes but I'll remember what's of critical importance for future generations."

"Very well," he said, "the story of my life. Hmm. What is that? Let's see. In the beginning I was born a little innocent baby – in Kagoshima. And even though Kagoshima is on the south end of Kyushu which is the southernmost island of Japan – not counting Okinawa which is Japan that is not Japan. Even though it was so hot there in Kagoshima, it snowed quit a bit."

"It snowed in Kagoshima?"

"Yes, very great snow, very deep. And very gray."

"Oh," I said, realizing what he meant.

"The snow where I lived came from the mountain and not from the sky and I would play in it and breath it as a boy." He went on. "I have great respect for volcano and enjoy very much the volcanic snow. It is more pervasive than snow from sky which melts. Sometimes for weeks it was everywhere - all over the streets and cars and coming in the homes and stores. Very stubborn. It gets into your motors and ball point pens and underwear."

He went on. Even though he was not a bad student, at the age of twelve Nanao decided not to go to the next level of school and, as it was not uncommon for a young person to start a profession at that age, got a job as an office boy in the local department of education. There he learned to use the soroban which we call an abacus which is a Greek word. Wonder how that came to be? They still use these in Japan and they tend to win competitions over electronic calculators. Like nimble kids today with computer games, he soon was able to move the beads on that ancient Asian calculator with blurring speed. And he was accurate. In time he was auditing the finances of all the schools around Kagoshima. The local newspaper did an article on him. At sixteen he moved to Tokyo where he continued to do office and soroban work.

Then at seventeen it was time for Nanao to go into the military which all young men did at that age because Japan was engulfed by militarism – had been so increasingly since before he was born. All he knew was Japan and living in a society run by the army. He choose the navy which was the most progressive branch of the armed forces. He was already feeling inside the rise of anti-establishment sentiment and that was the best he could do. He asked to be assigned to radar because he was interested in science and had gathered that radar technicians got to learn a lot of science. His wish was granted.

It was 1939 and Japanese forces were mainly in China, Taiwan, and Korea, but before long they had attacked Pearl Harbor and invaded Malaysia and Indonesia. Nanao was stationed somewhere on the southern island of Kyushu where he had grown up. He would spend a great deal of time looking at radar screens with nothing much happening. but eventually America started to bomb them so his job became much more important and interesting. But still he’d get stir crazy in his concrete underground bunker just looking at that radar screen. So sometimes he’d take a break and go outside – even when they were being bombed. Actually, that was the easiest time to take a break because then he’d already told them what was coming and from where and everyone would be busy shooting antiaircraft guns or running for cover. If it was peaceful and sunny out, say the type of day that would be perfect for a picnic of seaweed and octopus, he’d have to be hunkered down in the bunker minding his screen. Japan had become terribly stretched toward the end of the war so his schedule was rather full, mainly consisting of being on duty and sleeping.

Most of the communication he had with others in those bunker hunkered days was electronic – voice or codes over wires – and people were busy dodging ordinance and having their world come to an end so no one paid much attention when he started growing a beard. He was mostly by himself looking at his screen, his beard growing and eventually becoming quite long. Not all Japanese men can grow long beards but some can, due possibly to an extra bit of Ainu blood (Ainu being the original and Caucasian inhabitants of Japan who are the hairiest people on earth).

One day Nanao went out to get some sunlight and stretch his legs amidst the crashing of bombs and cacophony of antiaircraft rounds and spraying of machine gun bullets from strafing planes, all of which he’d become accustomed to, when a small American fighter got so close to him that for the briefest moment he could see the face of the pilot and the pilot had a big red beard.

So there was Nanao with his long beard and the fighter pilot with his long beard zooming close by and they looked at each other. And then the pilot circled back around and swooped down even closer and they waved at each other and he flew off – the pilot, not Nanao. But he’d too be gone soon for the war was almost over.

I told Nanao that his story reminded me, except for all the bombs and bullets, of an experience that Clay and I had driving into Death Valley the previous February. It was ski week and I had taken him skiing, well actually snowboarding, at other times, but the slopes would be sort of busy then so we went to Death Valley which I love visit. On the way we pulled off and drove down a rocky road to a vast scenic view of the valley, not yet Death valley, below and the rocky sandy ridge way way beyond and then Death Valley beyond that – and lots of wide sky. An added bonus for guys like Clay and me of going to just about any desert in America is that there are air bases nearby and testing grounds and stuffed aliens and whatnot and on this particular day we could hear jets zooming over and as we stood there looking over this extremely expansive valley there was another one coming from the distance. Now the airplane that went by Nanao was a lot more threatening than the one approaching us, but ours was a fighter jet going at incredible speed. It went right over us and then, swooping off to our right, circled way way around down into the lowlands in the distance and then, returning upward across the mountain ridge before us veered back and dipped down into the valley to our left and it came right up where we were and almost seemed to hover within reach for a second. It was a rare experience of astounding power and we could almost see the pilot’s face but surely didn't as it happened so quickly and noisily. It was so amazing and the pilot was obviously playing with us. We waved.

After the war, Nanao returned to Tokyo and got a job in publishing and worked there for a year or so and then, realizing he didn’t like that sort of life, decided that he would rather live with the bums in Shinjuku. So he did. He just quit working and started living out on the street. He liked the people and the lifestyle there. He’d sit out on the sidewalk or in a park and watch people go by and write poetry. And he’d walk. He really got into walking and he walked and walked in the city and then he walked out of the city. With Tokyo that takes a while. He walked on to the next city and then to another and another. He kept it up for years and went all over Japan, even visited Okinawa and eventually found a small island that he liked for two reasons: it was almost uninhabited though people came to visit and it was volcanic. Its name was Suwanose and there he founded a commune and they built homes and farmed. I looked it up on the Internet and found it was near Kagoshima where he was born (though I'd thought he said it was near Okinawa). It has one of the most active volcanoes on earth. They stopped an airport from being built there to destroy the isolated natural beauty that the tourists in the planes would come in to see. That's the first thing I remember hearing about him back in the sixties before we'd met, and reading, I think, a poem he'd written about it - that he was the founder of a hippie commune on an island in the south of Japan and that they were trying to stop an airport from being built there.

Nanao’s reputation spread and in the sixties when Allen Ginsberg went to Kyoto to visit Gary Snyder, they were told they had to meet Nanao so they did and they all became fast friends and they invited him to go to America which he did. He spent about ten years in America – in San Francisco and New Mexico and in the mountains and desserts. A friend of mine who knows Nanao says that Nanao walked from New York to California and back and forth a number of times and up to Alaska and so forth. All the walking stories I've heard about Nanao seem to me to add up to more miles than one could cover in a lifetime. But whatever he's walked, it's been one whole heck of a lot.

Folks at the SF Zen Center got to know Nanao because he never had a place of his own or any money so one of the communal houses near Zen Center would take him in as an honored guest. But he just wrote poetry and philosophized and didn’t tend to do the dishes so, after a while, he’d be passed on to another Zen Center house or hippy commune. And he’d write poetry and publish books and go to events like be-ins and concerts. He didn't always get his way. Kyokes in Kyoto was working at an environmental center on Yoshida mountain by the Yoshida shrine on the West side of the city - the same place where landscaper and Nanao buddy Sogyu is now. They were running a little hostel there a few years ago at quite reasonable rates and Nanao showed up and wanted a room for free and thought his name would do for legal tender but she said he'd have to pay like everyone else so he went off and found somewhere else.

Nanao has visited the commune on Suwanose through the years and says there are still about ten families living there and farming beneath the volcano. He's traveled to Europe and to Asian countries other than Japan and the South Seas. He’s been back to America. He was married a couple of times and had many lovers through the years, has two sons in the northern island of Hokkaido now and one who says he’s Nanao’s son who’s in the Bay Area and who Nanao would be happy to meet. And he has a daughter in Seattle who was due to have twins before long. He plans to come visit in the spring of this year. Maybe his plane is landing now. Or maybe he walked.

I told him I remembered a poem he had years before given me a photocopy of that talked about how much environmental damage Japan had done to itself - cementing creeks all over, cementing the coastline. I had an image of the coast cemented but I said that I'd lived in Japan since then and came to realize that he was probably talking in that poem about all the tetrahedrons, or what we called tetrahedrons lining the beaches and stacked out in the water to prevent erosion. A tetrahedron is a three dimensional shape composed of four triangular faces, but somehow that came to be what we called large cement forms of any shape that were piled in the ocean - sometimes stretching straight out into the sea, sometimes running along with the coastline. They were everywhere on Japan's circumference. And so were cemented creeks and sides of rivers and dams in creeks and rivers. A nation with unquestioned engineers gone crazy we agreed. I told him that I'd long had the idea to create a coffee table book of this phenomena. There were many different shapes and configurations of the tetrahedrons. Some of the cement objects were like jacks - star shaped. Maybe some were even tetrahedron shaped. I asked him what the book should be called. We agreed on "The Way of Cement." So the idea had started with just having a coffee table book on the "tetrahedrons" along the coastline but had expanded into cemented creeks, damns, sidewalks, buildings - all the many impressive examples of how cement has been used in Japan.

Speaking of which means writing of books, Nanao has three poetry books listed on Amazon.com: Let's Eat Stars, Break the Mirror: the Poems of Nanao Sakaki (with illustrations by Gary Snyder)- out of print, and Real Play: Poetry and Drama (Tooth of Times) - out of print. He translated poems by Issa Kobayashi and that book is called Inch by Inch: 45 Poems by Issa (La Alameda). There's a book by Gary Lawless with many contributions from various people on Nanao called Nanao or Never: Nanao Sakaki Walks Earth A. I don't understand the "Earth A" part but the title gave me the idea for the title of this piece. These books are published by Blackberry except the two otherwise noted.

I gave Nanao a copy of To Shine One Corner of the World: Moments with Shunryu Suzuki and of course signed it. It's a good book to give foreigners because it's all little vignettes. I told him how I still interviewed people for the oral history of the Suzuki days and that I'd write up something on our conversation and put it on my web site. And I asked him if he'd ever met Suzuki.

Nanao said, "Yes. I met him two times. Both times were at the Zen Center on Page Street in San Francisco. The first time Richard Baker took me. He introduced us. I said 'hi' and he said 'hi.'

"In English?"

"Yes. Everyone else was speaking English and we could too. And hi is not so difficult English."

"Suzuki Roshi loved to say 'hi,'" I said. "He said it a lot. I think it always had a little bit of the Japanese 'hai' in it - you know, yes in Japanese. There was always a lot of hai yes and hi hello and they were mixed together and had a sort of positive 'gambate,' go-for-it, encouraging sort of feeling.

"Yes," he said, and repeated the word a few times. And then, "Hello - we will do it!"

"So you said 'hi' and then?"

"That's all. Just hi. It was enough. I could see his great spirit and he could see me. And the second time I met him was when he was dying. Gary Snyder took me and we visited him. And we had exactly the same conversation we'd had before. Just 'hi' and 'hi' and we bowed our heads a little."

"So you and Suzuki Roshi had two meetings over the years and the sum total of what you said to each other in both meetings was four words - actually, one word four times?"

"Yes. It was just right. I am so happy to have met him. He was a great teacher for America."

Finding the Conch - the Japan story leading up to this story.