cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

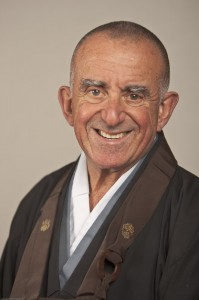

Les

Kaye page Les

Kaye pageLes Kaye's Zen Life - submitted to DC July, 2020, for podcast In 1956, I started work as an electrical engineer for IBM in San Jose, California. The company had recently opened a large manufacturing facility at the southern edge of the city. The feeling at this new IBM location was more like a small start-up company rather than a vast, forty-year-old corporation. High expectations for the innovative RAMAC disk drive were almost palpable. I could taste the ozone of excitement in the air. Career prospects seemed unlimited. In the mid-fifties, engineering graduates had their pick of jobs. Companies were offering lucrative starting salaries and attractive incentives. I didn't choose IBM for financial reasons; the aircraft industry in Los Angeles, for example, was offering a great deal more money. And smaller companies were offering more freedom. But IBM had certain qualities that I admired, including its reputation for outstanding management, technical leadership, and service to customers. It was also well-known for the strong loyalty and dedication of its employees. I thought it was the perfect location to begin a career: Plus, San Jose was only an hour's drive from San Francisco, the beach, and the mountains. From an early age, I knew that I wanted to be an engineer. As a kid, I enjoyed tinkering, putting things together, building houses and forts from building blocks and erector sets. My aunts, uncles, and cousins continually reminded me: “You should be an engineer.” In high school, I learned that engineering was an esteemed profession that paid well and offered a good future. I never had any doubts. In the mid 1950's, I was in the right place at the right time. California offered "the good life." Gasoline was twenty-eight cents a gallon. For $25,000, you could buy a spacious ranch-style home in a quiet, clean neighborhood that came equipped with the most ideal climate imaginable. The scenic, agricultural Santa Clara Valley - known as the prune capital of the world - was a new environment for conservative IBM, which up until then had been associated with small-town, upstate New York manufacturing plants; white-shirted, blue-suited salesmen; and the increasingly pervasive punch card. But change was in-process. The first interstate highway was under way, and space exploration was about to begin. It was the start of the Information Age; the "Valley of Heart's Delight" was soon to become "Silicon Valley." During the Thanksgiving weekend in 1958, I flew to Los Angeles to visit a college classmate. When I boarded the plane, I immediately took the seat next to Mary, a slender, dark-haired young woman. She told me that she worked at a hospital in San Mateo. I made a mental note. Back home the following week, we had our first date. A year later, we were married. In the fall of 1961, at a Friday evening cocktail party, I found The Way of Zen by Alan Watts on my hostess' bookshelf. I had heard about Zen but never read about it. The book caught my attention; I borrowed it over the weekend. At the time, Mary and I were living in a two-room cottage on a 900-acre pear ranch just off Skyline Boulevard, near Los Gatos. The autumn days were chilly and damp. On Saturday morning, I lit a fire, and for most of the next two days immersed myself in the magic of Alan Watts' spellbinding description of the history and practice of Zen. I was fascinated to discover a dimension of living, an attitude about life, that I had not known before. When I closed the book, I knew that my technically-oriented, middle class life was incomplete, that by itself could not provide balance. Watts' description of Zen struck a chord of authenticity. It was the time between the "Beat Generation" and the "Hippie" eras. Alan Watts was a regular feature on a local PBS radio station. I became a devoted listener and read almost everything he wrote. The extent of my interest in Zen was limited to reading and talking about it. I assumed that in order to be fully involved in Zen, it would be necessary to live in Japan for several years. For me, that was not a realistic option. I planned to raise a family and continue my career just where I was. In the fall of 1966, I was pleasantly surprised by an article in the Chronicle that described the San Francisco Zen Center, amazed to discover that actual Zen practice had been taking place for several years close to home. A few weeks later, following a business meeting in the city, I located the Zen Center in the neighborhood known as Japantown. I was not prepared for what I found. Expecting a quiet, secluded, Japanese-style temple, I encountered instead a turn-of-the-century building facing the noisy traffic of Bush Street. The unlocked front door was guarded by two tablets. To the left, in stone, were chiseled the ten commandments in Hebrew. (The building was originally a synagogue.) Japanese calligraphy was painted on a wooden block to the right of the door: the building was now the home of the Japanese-American Zen Buddhist congregation. I entered the old, musty structure. The dim hallway was quiet. The smell of incense mingled with another familiar, ancient fragrance: chicken soup. Or so I thought. Later, I was to find out that it was the aroma of Japanese miso soup. I opened a door and entered a small office, encountering an elderly Japanese man, wearing a hat, reading a Japanese language newspaper. He paid no attention to me. I thought, "Is that the Zen Master?" On the other side of the office were two very tall, very bald young men, operating a hand-crank mimeograph machine. I asked about Zen practice. One of them said: "Just sit." I had no idea what he meant. I glanced at the man reading the newspaper. "Is that the Zen master?" I wondered again. I explained to the two young men that I lived in San Jose, fifty miles south of San Francisco. They told me about an affiliated meditation group closer to home in Los Altos, where the abbot of the San Francisco center, Zen Master Suzuki-roshi, traveled each Wednesday evening to lecture and lead meditation. In early December 1966, Mary and I found ourselves at Haiku Zendo, a meditation hall created from the garage of the home of Marian Derby. Its name derived from its 17 permanent spaces for meditation, the number of syllables in a Japanese haiku poem. The room could be made to accommodate up to 30 people, using additional meditation cushions on the floor. Marian gave us basic instructions in zazen, seated Zen meditation. That first evening was difficult. The unheated meditation hall, or zendo, was freezing. Our legs and backs were cramped and sore. Understanding Suzuki-roshi, whose English was still tentative, was difficult. He spoke a great deal about "pedrachs." Years later, we figured out that he meant "patriarchs." On the drive home, we agreed, "Never again, that's too painful!" Nonetheless, we returned the following Wednesday. What brought us back? Partly it was Suzuki-roshi's quiet confidence and gentle humor. His words conveyed something fundamentally true that I didn't quite understand and his manner expressed and encouraged trust. In addition, Marian made us feel very welcome. Despite the discomfort, I sensed something subtle in the activity of zazen, which did not seem to involve any activity at all, except trying to sit still and be quiet. We commuted from San Jose to Haiku Zendo two or three times a week. The Wednesday evening schedule included meditation and lecture, with tea and a chance for socializing afterward. Suzuki-roshi and Katagiri-roshi alternated coming from San Francisco Zen Center on Wednesdays and staying overnight in Marian's home. Thursday morning included meditation, a short lecture, and an informal breakfast in Marian’s dining room. A Saturday morning schedule provided an opportunity to experience the basic forms of traditional Zen monastic practice. It included two periods of zazen, beginning at 5:30 AM, breakfast in the meditation hall, a work period, and a later meditation at 9:00 AM. Greeting the first light of dawn in silent zazen continues to be a quietly profound experience. I fell in love with the formal monastic-style breakfast, using traditional Zen monks' eating bowls known as oryooki. I was so inspired by this reverential, ceremonial way of serving, receiving, and eating meals, I eventually wrote a small book about the construction and use of oryooki. The work was simple: we brushed off the meditation cushions, dusted the corners, mopped the floor, cleaned the altar, swept outside, and washed dishes. Sometimes we helped Marian with yardwork. The Saturday work period was an important element of the practice at Haiku Zendo. Not only did it allow us to repay Marian for her generosity, it also enabled us to take care of our communal practice place. The latter reflects a crucial point of spiritual practice - its giving nature, its orientation towards others. Other key elements of Zen practice - zazen, study, and being with the teacher - are at risk of becoming self-oriented activities if not balanced by the practice of giving time and effort to others, to taking care of the community, giving up any notion of personal benefit from doing the work. Soon after we started going to Haiku Zendo, Mary and I bought our own cushions and began our weekdays with zazen in our San Jose living room. In June of 1967, we participated in our first one-day meditation retreat at the San Francisco Zen Center. During the break following lunch, we took a walk on Bush Street. The early summer day was cool and clear; a gentle breeze came from the bay. Mary said, "It's too nice to go back to that dark room." So we drove over the Golden Gate bridge to Sausalito and spent the afternoon on the deck of Zack's, a pub that shared the lagoon with houseboats and seagulls. Commitment and discipline had not yet arrived. Haiku Zendo had its beginning in early1964 when Suzuki-roshi was visiting friends in Redwood City. He casually remarked that if a good meeting place could be found on the Peninsula, he would like to begin a weekly meditation group. In November, the first zazen and lecture was held at 1005 Bryant Street in Palo Alto. Three or four people attended the first few Thursday morning meetings. In April, 1965, an evening group was established in Redwood City. In July, the morning group was moved to the living room of Marian’s home. An informal breakfast was added, following the brief lecture. The family-like discussions at the breakfast table with Roshi were as popular as his talks. In 1966, the evening group also moved to Marian’s home. Tea and cookies were served following the weekly lecture. Socializing could last until 11:00 PM. When Marian’s son went off to medical school, his room became available for Suzuki-roshi to stay over- night. The schedule was changed to Wednesday evening and Thursday mornings. Most often it was Marian who drove to San Francisco to pick up Roshi, and take him home the next day. Starting in 1965, Marian recorded Roshi’s morning lectures. These “little talks ”were rarely longer than fifteen minutes. Marian transcribed the tapes each week, going over each transcript with Suzuki-roshi. When the idea of creating a book from the lectures arose, it was given the title, “Morning Talks in Los Altos.” In 1967, the transcripts were given to San Francisco Zen Center for final editing. The book was given a new title, “Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.” In 1968, Trudy Dixon, very ill with cancer at the time, took on the editing job. Trudy’s deep understanding of Zen and her great gifts as a writer resulted in the respected and influential book, published in 1971. Trudy died before its publication. After a year of meeting in Marian’s living room, the number of people attending zazen and lecture had grown to the point of overcrowding. Marian offered to convert her garage into a zendo to be used for daily meditation and weekly lectures. Suzuki-roshi designed a traditional Japanese- style zendo to fit the small space. Construction was begun in June, 1966, performed entirely by Sangha members. Haiku Zendo was officially opened on August 4. By 1968, Marian felt the need to deepen her Zen practice and determined to go to Tassajara, the first Zen monastery outside of Japan, created in 1966 by Suzuki-roshi and the San Francisco Zen Center. However, her two teenage daughters were still living at home and she did not want to disrupt Haiku Zendo. She asked Mary and me if we would consider moving from San Jose to her home to be administrative caretakers and take care of her daughters. We wondered if we could manage the responsibilities, the higher mortgage payment, and the additional commute time. We concluded that it was an exceptional opportunity to get to know Suzuki-roshi, learn about Zen practice, and help establish it in the U.S. We moved to Los Altos with our two young children in September. In 1969, Suzuki-roshi suggested that Haiku Zendo invite Kobun Chino-sensei to return to the U.S. to become its resident teacher. He arrived in February, 1970, and lived with us for nine months. He married Harriet whom he had met at Tassajara on his first visit to the U.S., when he stayed for two years. I began to think about becoming a Zen monk, one of Suzuki-roshi's disciples. As I felt drawn closer to him during the previous two years, I became more and more aware of the depth of his effortless expression of patience and kindness. His quiet, natural way demonstrated that these were qualities inherent in everyone. I wanted to understand how he did it, to absorb his way of being in the world. At the same time, I wondered if I could live up to being one of Suzuki-roshi's possible successors. Emotionally, I was too analytical, too impatient, plagued with a tendency to be quick to judge. I was far from his quiet manner of total acceptance. How could I carry on his way, learn to express his selflessness, and be as encouraging to others as he was? Was I sincere in my desire to become a monk or was it a scheme to gain self-esteem? Was I constructing a facade, an appearance, to cover up something about myself that I did not want to see? I became painfully aware that I liked the idea of being known as a monk, as one of Suzuki-roshi's students. The awareness made me feel unclean, as if I were sniffing the faint aroma of my own ego. I spoke to Kobun about my confusion. He just said, "You should go ahead." Even with his encouragement, I remained skeptical. For several months, I struggled with my doubts, arguing with myself back and forth. "I'm too judgmental," I would say; "You'll get over it," I would respond. Little by little, I realized that I was being too self critical, neglecting to trust both myself and the practice. Finally I started to understand that it was not necessary to be perfect. It was more important to continue to practice with determination, to try to be aware of self-oriented tendencies, to try not to allow them to poison circumstances or relationships. It meant proceeding with confidence, even if accompanied by uncertainty. I didn't know what it meant to be a Zen monk in modern America. Nobody could have; the concept was too new. I understood only that I wanted to be a monk while continuing to work and take care of my family, to develop an integrated, balanced life, expressing spiritual practice in the complexity of the everyday world. Was it possible to have the true spirit of a Zen monk while living a suburban, corporate life? Could I live completely in the world, fully involved, without seeking anything beyond how to live the authentic life? In March of 1970, I made arrangements to meet with Suzuki-roshi to talk about becoming a monk - his student - in the Zen tradition, as well as to explain my own doubts and reservations. Driving to San Francisco on that cold, drizzly evening, the glare of oncoming traffic made the slick road difficult to see. The city was embraced by fog. Suzuki-roshi was waiting for me in his small Zen Center apartment. It combined artifacts of two cultures. America provided glossy, enamel-white walls, a steam radiator with connecting pipes running along the baseboard, electrical outlets, and high sash windows. From Japan there were delicate Oriental statues, scrolls of elegant calligraphy, and mysterious Buddhist texts. The fragrance of incense lingered everywhere. We sat on cushions next to the window overlooking Page Street. Suzuki-roshi poured me a cup of tea. I told him that I wanted to be his disciple. He asked me why I wanted to become a monk. As I started to speak, he immediately stood up and without a word went into an adjoining room. I sat alone with my teacup, looking out into the damp night, wondering what was next. In a few minutes, he returned with his wife, known to everyone simply as Okusan. She carried a measuring tape. They stood me up. Together they took my measurements: chest, waist, height, arm length. Then he said, "Your robes will arrive from Japan in six months. They will cost $150. Thank you for coming. Good night." I stepped into the dim second floor hallway of Zen Center as he closed the door behind me. It was his way of saying, "Yes, you can become my disciple." He asked no questions. I did not have a chance to explain. So at the age of 37, I was going to become an American Zen monk, a disciple of a perceptive, down to earth, determined, unselfish Zen master. It was a rare opportunity that I was being given, a chance to bring together several worlds, to follow my intuition about the relationship of spirituality to everyday human activities. I wanted to understand how it can be expressed at work, at home, and within social institutions. It was new territory; there were no instructions on how to proceed. One thing I was clear about. If I was going to be a Zen monk - even part-time -I had to follow the fundamental Buddhist tradition of home-leaving. It began with Buddha himself and continued with the young men and women who gave up their everyday lives to become monks and to live with him in community. I felt it was necessary to attend a 90-day practice period at Tassajara. But it meant leaving my wife and two young children for three months. Mary told me that if I felt strongly, it was OK with her. I was granted a three month leave of absence by IBM - without questions - and spent September through early December of 1970 at the monastery. It was difficult, giving up the comforts, pleasures, and independence of middle class life, in exchange for arising each day before sun-up, following a strict daily schedule of meditation and work, often in cold and rain, with little free time. I learned about attachments and how stubborn my mind was to let them go. In January of 1971, I was ordained as a Zen priest by Suzuki-roshi in a ceremony at Haiku Zendo, Roshi passed away from cancer in December of that year. Kobun never officially became my teacher. We simply continued to work together at Haiku Zendo. He was the spiritual leader while I tried to manage the administration. Haiku Zendo established a steady practice and presence over the next several years, attracting many from the San Francisco peninsula. In 1979, based on the need to move out of a private home and create a more accessible and spacious practice center, the Sangha raised $40,000 needed to purchase a small former Pentecostal church in an older, quiet neighborhood on College Avenue in Mountain View. The new zendo was named Kannon Do, “place of compassion.” In early 1984, Kobun told me that it was necessary for me to obtain Dharma transmission, recognition as a teacher and authorization to have students, in my own lineage. His own lineage was different from Suzuki-roshi’s. He said he would call Suzuki-roshi’s son - Hoitsu-roshi - in Japan and arrange it. Later, I followed up with my own call to Hoitsu and told him I would like to come with Mary in April to Rinsoin, his family temple. He said “Please come.” On April 1, we arrived at Rinsoin in the foothills of the small city of Yaizu to learn that Hoitsu and his family were making plans for a very large Jukai , a lay ordination ceremony for 400 people from Yaizu and surrounding prefecture. The ceremony was held about every thirty years; this year on April 9. The Suzuki family was wonderful. Hoitsu’s wife, Chitose, was joyous, energetic, hard working and full of good humor. Narumi, the eldest daughter, was in high school. The younger daughter, Kayoko, was in middle school. They were both a bit shy with us, as expected, but greeted us with courtesy and attention. Shungo, the younger brother- around eight - was not shy: boisterous and demanding, full of young boy energies. He was in Little League, so wore his uniform in the temple at all times and watched Japanese league baseball whenever it was on TV. Years later, he would succeed his father as head priest of Rinsoin, following the family tradition [not yet - 8/2020]. That first evening, Mary, Chitose, Hoitsu and I sat around the low dining table to talk and get to know each other. Hoitsu and Chitose thanked us for coming to Yaizu to help prepare the 500 year old temple for the Jukai ceremony. I sensed that he did not know the primary reason I had come to Japan. When I mentioned that Kobun had sent me to talk about Dharma transmission, he and Chitose were startled; it was new news to them. Apparently, Kobun had not mentioned it when he called. Next day, Tuesday, Mary and I joined the temple preparations. We worked in the garden and helped townspeople strip and replace rice paper on the sliding door screens. Wednesday I decided to clean the large koi pond in the garden. It was overrun with very dense and slimy algae and had not seen koi in years. I placed a long ladder across the pond to hold large plastic buckets. With pant legs rolled up, I waded in the pond, scooping up armloads of algae into the buckets, which I carried away and emptied down a hill, near a stand of bamboo. I made a number of trips in and out of the pond. As the afternoon went on, more and more faces appeared at the open temple doors and on the deck, family and visitors wide-eyed at what I was doing. The weather was still chilly at night, so that evening on the way to bed, Hoitsu gave Mary and me each a small bottle of sake. He said it was “medicine” against the cold. Next night, on the way down the corridor to our room, we heard a voice over the temple loudspeaker system: “Kaye-san, you forgot medicine.” We took “medicine” to our room every night. [These are very small iittle bottles of cold sake, comperable to a glass of wine] As our week in Rinsoin was coming to a close, Hoitsu found me alone and said, “Come back next year for Shiho (Dharma Transmission). Stay one month. Leave wife home.” So in April of 1985, I returned to Rinsoin to receive Dharma transmission. I expected there would be extensive training and time spent with Hoitsu who was to become my Zen mentor. The month was interesting, exciting, hard work, and great fun, but not exactly what I expected. Each day began with zazen around dawn. Before breakfast - as well as before lunch and dinner - I performed ritual 108 bows, accompanying myself on the Bonsho, the large altar bell. Mornings I tended to the altar in the Buddha hall, and dusted the statues and effigies of the past generations of teachers in the lineage. Most of my time was spent helping the Suzuki family with household chores: washing dishes, hanging up and collecting the family laundry, taking care of the furo, the bath tub, weeding in the garden, and, in early afternoon, starting the wood-fired boiler that provided hot water for the entire temple. This task required splitting logs for firewood., bringing to mind the insight of Layman P’ang: My spiritual activity: Drawing water and chopping wood. I spent most evenings with the family, late night talks with tea and sake. Late on a warm afternoon, I was pulling weeds and trash from the vegetation growing along the bank of the creek that ran down from the mountain past the house. I turned slightly to my right and came face to face with a two inch lizard, staring up at me. We gazed at each other for an eternity - perhaps three seconds - when he suddenly ran off into the weeds. I was left with a feeling of composure and confidence. I cannot explain what happened. I only know that this prehistoric creature and I had made a connection without distinctions. The Dharma transmission ceremony took place on May 8. During the month, I had became very close to the Suzuki family, especially Chitose. On May 10, she drove me to the train station for the start of my return trip home. We both had tears in our eyes as we said goodbye. In late 1985, Kobun appointed me teacher of Kannon Do, when he moved to New Mexico to assist in establishing a new Zen Center. In 1988, the Kannon Do Sangha invited me to be its first abbot. In 1990, after ten-plus years at College Avenue, the Kannon Do membership decided to create a larger center in order to provide more facilities to accommodate its growing activities, as well as to widen its accessibility to the larger community. Following ten years of fund-raising and three years of searching for suitable property in a tight real estate market, a one-half- acre property, with two houses, was purchased in 2003 for roughly $800,000 at 1972 Rock Street. An additional year was needed to obtain the required Conditional Use Permit from the city of Mountain View. Final plans for the facility were drawn in 2004, construction took place in 2005, and the Sangha moved into the new Kannon Do in 2006. A formal dedication ceremony was held March 3, 2007. Individuals in today’s world are seeking freedom from the isolation that comes with continual change and a speedy, stressful environment. Part of the mission of Kannon Do is to offer a welcoming, supportive atmosphere for its members, as well as for others who have yet to arrive. Its vision is to provide opportunities for individuals to explore Zen practice, to discover their interconnection with one another, and to reveal their inherent wisdom. As Huston Smith wrote in the foreword to my first book “Zen at Work,” By entering America in this century, Buddhism has resumed the eastward march that took it first to China, then to Korea and Japan. But its present step differs from those earlier ones in bringing it not just to a new place but to a new time: modernity. This poses a greater challenge than the previous migrations did, and the question is whether Buddhism can live up to it. |