Interview with Mike Dixon

Mike

Dixon link page

Portrait of DC by Mike Willard

Dixon -

view on his website

Didn't date this but I can tell

that it's early by what I say - like not knowing who the first

students were. So I'd say 1993.

Mike's artist name is

Willard Dixon. His full name is Willard Mike Dixon. He's not

only a wonderful artist but gifted musician as well. He jams with

a jazz group. "Our quintet is called Studio Five. consists of sax,

bass ,drums ,piano,and guitar." He plays the sax.

This was an interview that's

really more of a conversation done sometime around mid 1994 I

guess. It was transcribed by Elizabeth Tuomi sometime back then

and edited by me 5/31/10 - DC

Mike did the cloud paintings at

Greens restaurant and the fly for Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind.

MIKE DIXON

In the long run, my own life, meeting Suzuki and following

the way he taught me, has colored everything. It's

something that continues. I feel now that I'm getting

older, more the pull into practice. It's different

now. In many ways it's a lot easier to practice

now. There's so much baggage that's gone.

(Tape 1, Side A) –

DC: What's your most vivid memory of Suzuki?

MD: Trying to remember when I first saw him.

Somebody at the Art Institute told me I should go over and see

this guy. I did go over. That was probably '62 or

so. I went and started wanting to go back. I had

this feeling you have sometimes that somebody's is a lifetime

friend. Or that someone is going to be very important in

your life. It's unexplainable, really.

It's hard to say exactly why. Some feeling of trust

there. And you trust your own feelings about that

person. He seemed so interesting. There seemed to be

so much attention of some kind there. It was something you

just naturally wanted to continue. As I was leaving, the

first lecture that I went to, I was walking down the stairs at

Sokoji, and just as my head got to about floor level I looked

through the banister posts as I was almost disappearing from

view ?? I looked into the room and he was looking right at

me. I told some stories that I wrote in the Wind Bell

anniversary issue – a lot of people were telling stories about

Suzuki. I mentioned a couple of interesting things in

there. One that I liked in particular. Every

Saturday we would clean up everything and sit three or four

zazens and lecture. I was sweeping away, and some new guy

came in. Usually I would just keep to myself and not be

terribly helpful to new people who were wondering what they

should do. This guy was looking around, wondering what to

do. I gave him my broom. Just then, I turned, and

Suzuki was holding his broom out to me. It seemed a

perfect sort of teaching.

DC: Maybe because there's such a physical component to it.

MD: Yeah. When I first started going I was living

down on Pierce Street and going to art school. I was

living with a guy I'd gone to the Brook Museum with. Trudy

used to come over on weekends. Eventually I took her to

see Suzuki, when we were still living over there. She was

very much into studying philosophy, and had studied at Wesleyan

and was continuing graduate studies at UC Berkeley. She'd

been studying Heidegger and Wittgenstein. She was curious

about it. I took her in there, we were staying toward the

back, and he talked for a while. Then he started talking

about philosophy. The study of philosophy, as opposed to

the study of Zen, or practice. He was always holding out

the idea of practice to us at that time. He didn't have so

many students then. As opposed to just thinking and being

curious about it. The idea of actual sitting practice was

different. He told a story about a philosopher he knew in

Japan who had killed himself. Just as he told this story

he looked very intently at Trudy, who was studying

philosophy. She went backward a few inches. It

seemed very relevant to her. Then we moved to a place on

Larkin and Pacific. We continued to go to lecture for

awhile. Then one day we got up and said why don't we just

start sitting, start practicing, and see what it would be

like. We did. And we continued. That was

probably '63.

DC: What was he teaching?

MD: It was practice. Zazen. To me that was the

essence of it. One time we had dokusan. He asked me

if I had any questions. I said zazen answers my

questions. He said, yeah, that's right. If there's a

pencil sitting here on this tatami, and all of a sudden it's

gone, one person will say, oh, somebody stole my pencil.

Another person will say somebody just borrowed my pencil.

I took that to mean that you can really only answer your own

questions.

DC: You have your own interpretation of things.

MD: Our mind, after sitting for some sessions, just

naturally calmed down. We would think about

enlightenment. What is it? Is it something we were

going to get? The idea of it. It seemed like the

more we went on, the more we wondered if there really was any

such thing. Suzuki used to say things like, on my second

enlightenment ??

DC: He didn't say that later on.

MD: I remember him saying things like that. Like you

might have a small enlightenment here, or a larger one later, or

you might have many enlightenments. That was my

feeling. That is my own experience and I think that's

true.

DC: Ananda said that Suzuki always maintained that he

wasn't enlightened.

MD: Well, if you say you are, you aren't. But you

can't say that you aren't either. You don't say that you

are, and you don't say that you aren't. Suzuki told me

once, he said, "I knew a farmer in Japan who was just like a Zen

master. He was a natural man, a simple man, but he was to

all intents and purposes a Zen master. The only difference

was that if you said to him, you are a Zen master, he would say,

no I am not." He had a kind of innocence. You would

have to go through a lot of stuff to come out the other side and

say, "Ah, so desuka," (Is that so?) or something like

that. Or not to deny it, not to claim it.

DC: The subject of enlightenment is what I want to deal

with precisely because we never have. It's something that

hasn't been discussed much in Zen Center history. I don't

particularly like to talk or think about it. It seems sort

of sophomoric to do that. But Ananda brought it up first

thing. "First and most important. Suzuki Roshi was

not enlightened!"

MD: I don't know what he meant like that.

DC: I called him up last night and got him to talk about

it more.

MD: I think he was beyond enlightened or not

enlightened. To think about that is to miss the

point. And I think that was Suzuki's teaching. We

don't want some fancy idea about practice, or some excessive

experience. The point is just to see things as they are in

the moment and not to attach to things, to let things change as

they go, and let them come and go out. That's more

interesting than being enlightened. As soon as you become

attached to any enlightenment you might have had, it will be a

barrier to you. People who talk about it that way are

asking for trouble.

DC: Helen Tworkov wrote an editorial for Tricycle in which

she talked about how Zen Buddhism in America is developing and

at a crossroads. Sort of therapeutic, socially

responsible, and is forgetting about enlightenment which is the

first goal of Buddha. That's how Buddhism began, with his

enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. She said Suzuki Roshi

never talked about it. I mentioned that to Michael Katz

and Michael's read all the lectures several times and listened

to them all and he said, oh no, he talked about enlightenment a

lot. But subtly, maybe. He sure didn't emphasize the

sort of enlightenment you hear from people who were going to

Yasutani. Or working with Maezumi. Or with Tai

San. To quote Tai San, there's only two types of

people: those who know and those who don't. My god,

if he's an example of those who know ?? that's so

ridiculous. There's a whole mind field of bullshit.

MD: Especially when you get into ?? when you get in some

position over other people. His teaching was so focused on

not being caught by anything or attached to any particular idea.

DC: I studied at this Rinzai temple in Japan. It

would have been impossible for me to get into it like

that. They were going after enlightenment and all

that. I like sitting and having sanzen (dokusan) and not

doing too much. I was on a totally different trip from

everybody else. But the teacher was so cool, he didn't

care. If he didn't care, nobody else cared. It was

partially because of who I am before I came to Zen Center, but

partially because Shunryu?san knocked it out of me and Katagiri

too in that Soto trip. It's controversial in a sense in

the Zen world.

MD: As soon as you sit your enlightenment is there, stuff

like that, all the time. You hear that enough you begin to

believe, that's right. Which, on the other hand, doesn't

mean ?? and Suzuki said one time ?? that you shouldn't just sit

on the steps and play your guitar all day. Meaning that

you don't just give up and do nothing because everything has

Buddha nature.

DC: I think a quote from him is, "Everything you do is

right, nothing you do is wrong, yet you must still make constant

effort."

MD: I would have the feeling, in sesshin especially, but

it was there all the time with him, that you would think you

were putting out this huge effort. You didn't have much

more to give. But just by looking at him you would feel

that you'd just barely started, hadn't even scratched the

surface yet. There just seemed to be this infinite well of

intention or effort that was under there somewhere. I

think our whole thing about enlightenment is, in a way, a kind

of ?? he used to talk about candy. He'd say it's OK to

give young students some candy, so they would get involved here

and get going on something. But really, you have to be

careful about that. Like selling intoxicating liquor is

the same thing. I think a lot of it has to do with

building up the intensity effort. It's the effort which

does lead to a kind of breakthrough. Enlightenment is not

something that you get. Enlightenment is realizing

something that's already there. It's more like getting rid

of, than getting something. I think that's the big mistake

that everybody tends to make.

MD: They think they're getting some experience from

outside that they never had. When you build that kind of

intensity of effort that you can experience in a sesshin it

tends to strip away stuff more than anything else. Then

you're just left with yourself. That's enlightenment, I

think.

DC: He also didn't like us to sit too many sesshins.

MD: He didn't seem to like us to think that that was more

important than everyday life.

DC: He was Apollonian. (v. Dionysian). Ruth

Benedict. Dionysian was more like the way I was, more

extreme. Apollonian was more steady?state.

MD: I think of Apollonian as coming from ?? emphasizing

harmony, rational. Dionysian is more concerned with the

dark side and with passions and working through that. I've

always felt that Suzuki had a tremendous well of humor,

too. He had such a powerful presence that even though he

was a good speaker and knew a lot about the history of Zen and

Dogen, it didn't seem that was his sole effort to me. He

would often say things to that effect. Emphasizing the

practice. One time in the early days a bunch of us were

sitting in Sokoji. There were only about 15 or 20 that sat

regularly. We'd been sitting ?? and it was very intense in

those days because we were finding our way and we didn't quite

know what we were doing. I don't think Suzuki knew quite

what he should do with us either. One morning we came in

and we were sitting ?? like a Saturday and it was the second

sitting, and all of a sudden he was talking up at the altar and

his voice got low. All of a sudden he jumped up really

quickly and started hitting us all with the stick. He just went

around the whole room just one after the other, very fast.

He'd never done that before or anything like that. It was

accompanied by this tone of voice which almost seemed like he

was mad at us. He roared around the room hitting us and

boy did that wake us up in some way. As a group.

Later he said something about that, and about the fact that he

felt that something was wrong. He didn't know quite what

it was, something about our attitude. The way we'd been

practicing was not right. That we were all doing something

a little off that he felt needed correcting.

DC: He did the same thing at Tassajara years later.

MD: One time I said something to someone else, that I

thought in the early days my experience was that there was

something about it that seemed particularly intense or difficult

at times. He heard that and he jumped right on it and

supported it. Yes, that was really true. When we

first started sitting there was something going on that was ??

in my own mind it was finding our way ?? something that made it

particularly intense at times.

DC: This included who?

MD: Betty Warren, Della, Trudy, myself, Dick, Bill Kwong,

Phil Wilson, Norm Stiegelmeyer, Graham, Paul Alexander, Fran

Keller. And then Mel (64) and Ed (66) came a little

later. Ed and his brother Dwight. Mel was living at

one point with Dan Moore ?? the visionary ecstatic poet.

Used to smoke a lot of dope. A lot of people did.

Mel moved into his house. Mel played

recorder. Mel taught me how to read music. I got my

flute and we used to play music together and I learned how to

read with him. That was before he came to Zen Center. I

think Dan Moore brought him to Zen Center.

DC: I remember Dan Moore coming around later. What

about Daniel Eggink Remember him? Very

intense. I heard he was the first guy who shaved his

head. He was sleeping in a car in Big Sur that got hit by

a car and almost died from that and came out of it a little

weird. He was involved in drugs. Super

intense. Ended up having a nudist/guns commune in

Montana. Everybody walked around nude and they had a lot

of guns. He seemed slightly dangerous. What about

this guy Bill McNeil? Some guy early on, I think he went

to Japan and really didn't like it and quit. Maybe he quit

in '62, '63.

MD: Must have been before my time. Wasn't Bill the

first guy who went & sat with Suzuki?

DC: I've heard that. I've also heard Bill say that

Paul Alexander was there when he came. Bill is one of the people

who really took the Zen thing seriously. He's still doing

it. It's hard to get in on his schedule. He's very

sweet. He goes every year to China. He really

believes in it.

MD: I haven't been up to his place. I want to do

that. I haven't seen Bill for years. Phil Wilson

really disappeared. He burned his robes I hear.

DC: Dan Welch did too. Reb wrote Dan a letter.

Dan sent him back the ashes. He's gotten over that.

In fact, he and Dick just went to Japan and Europe together.

MD: One thing that happened between Suzuki and

myself. I don't think I've ever told anybody. In his

office one time, I was facing away from him and he said, "You

know. You have to be my successor." My blood went

cold. I pretended that I didn't hear anything. I

left the room. I thought about that for awhile. I

never mentioned it to him and he never mentioned it to me.

I figure he probably tried that out on a lot of people.

DC: He said to me once that we'd be starting temples all

over and people would be going out and Zen Center would

spread. He said I should go to Texas and start a temple in

Texas. I said no I'm not going to Texas to start a temple.

MD: I have the feeling now that he was just putting out

feelers for possibilities in those days, who was up for

it. And I definitely wasn't. I was trying to be an

artist and the idea of leading a Zen thing, or even having any

responsibility beyond a certain point was not what I wanted.

DC: Maybe he wanted to see which direction you were going

to go in. The lay direction or the priest direction.

I think one of the things that upset Ananda about Zen Center's

development when we got Tassajara was the shift from lay

community to priest?led community with hierarchy and more rules

and ceremonies.

MD: Yeah. I think Ananda always felt it should have

remained small ?? kind of like it was in the beginning. Go

on like that forever. All the stuff that happened because

of Dick somehow got off the track. Somebody used to say ??

I don't know if it was Ananda ?? that Suzuki himself felt that

way eventually. I don't know if that's true or not.

DC: He'd say things like Zen Center's getting too

big. I don't know what to do with it. Peter

Schneider told me that Suzuki would say let's just you and me go

off.

MD: In my own mind related to that story I told you about,

that I'd never realized before. It must have been about ??

when we lived in Mill Valley ?? must have been '65 or '66

. He gave all of the old students a rakusu. They

were the kind you order from Japan. He had this little

ceremony and he gave everybody in the original group one except

me. I'd been sitting longer than some of those guys.

Dick got all pissed. He said, "How come you're not giving

Mike one? What the hell's wrong with him?

DC: I would have been so hurt.

MD: I was cool. And for some reason I wasn't hurt

particularly I just thought it interesting. Trudy went in

with everybody else. I wasn't even there. They all

got their rakusus. Trudy's was blue, like the ones we make

now, but it was bigger. It looked machine made and had a

big circle on it. I was wondering what was going to happen

on this. Trudy said, "Suzuki asked me, ‘What did Mike

say?’" I knew that was coming up so I was cool. When

she came in with her rakusu, before she said what Suzuki said I

just said, "Oh fantastic. Congratulations." I did feel

very nice about it. I didn't really care, but I was sort

of wondering. Then later she said that Suzuki had asked

what Mike had said. "So I told him, oh he gave me a kiss,

and said 'This is great, Trudy. I'm so happy for

you.'" So that's what he got back from me.

DC: Were you sitting with the group at the time?

MD: Yeah, of course. I did everything. I was

treasurer.

[This is a mystery to me DC

- See this info at the bottom of the

page.

DC: Typical Zen mind fuck, man. I would be so

jealous if people who came after me got ordained.

MD: You could say, well, I'm special. I didn't get

one. I could go on that trip if I wanted to. So then

later when he was getting on in years and I thought well, I want

to get a rakusu from Suzuki. I want to get my name from

him. All the other guys got names. Trudy was Bai Ho

Sesshin ?? Winter Plum blossom. I just told somebody that

I wanted to make a rakusu. That was when we were at Page

Street.

At some point when I knew an ordination was happening I said I

wanted to sew a rakusu. I was the leader of that group,

the head student. I bowed and said, "Please accept

us." And he said, "Yes, I will." So he wrote on the

back of my rakusu. My name is Ko Kai.

What would your idea be about what Ko Kai means?

DC: Ko Kai could mean something ocean. It could mean

dark ocean.

MD: I'll tell you what he told me it was. When he

was dying I went up and talked to him and I asked him, what does

Ko Kai mean? He said it was Out of Kalpa Camellia Tree.

(discussion of calligraphy on Mike's rakusu)

MD: Dick said the camellia is called the guillotine flower

and it's like death because it all of a sudden falls off.

Suzuki said the name was something very old that just comes

out. It seems to be one of those things that's very open

to interpretations.

DC: I'm sure this is the same ordination I was in on.

MD: Do you remember me leading it? You were already

ordained. I just waited around until I thought, well, he's

going to die soon, I've got to get ordained. It was an

ordination before he was sick.

DC: It's interesting that he would single you out for

that. It's just a personal thing between you and him.

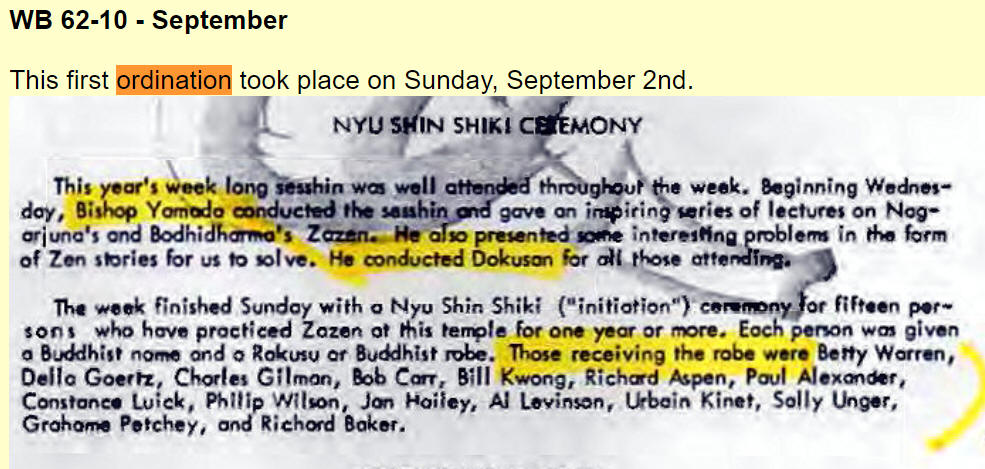

DC note: 7/2020 -

I was lay ordained in the summer

of 1970 and the next one was summer 1971. These are the first

since 1962 as far as I know.

MD: But then I thought ?? because I told you that story ??

that he was just giving me what I wanted. He told me there

had to be a successor and I didn't even answer him. So why

should he give me a rakusu? He figured, he doesn't want a

rakusu. And he was right.

DC: Oh, god, maybe that's it.

MD: I just finally figured that out.

DC: Suzuki talked with Silas and various people.

Dick became his successor because he was the one who had

demonstrated the ability to that beforehand. Plus ?? and I

talked to Suzuki about this ?? Does this mean he's enlightened

or something? No no, just means he has good

understanding. Don't make too much of it. He said

also, full commitment. He saw he had the organizational

and fundraising ability so he seemed like the right

person. But people who say that he was given that just

because of his administrative ability ?? that's

ridiculous. That's not enough.

MD: As I told you on the phone, when we had that election,

he became president by one vote, I missed it by one vote.

I think I probably voted for him. I think he took it as

kind of a mandate and he just took over. From that point

on he was gangbusters.

DC: Was this the point where Bill left?

MD: Bill was still around.

DC: Bill has told me that story in great detail. How they

had an argument over who would hit the bells. Suzuki had gone to

Japan, the first time – 64 or so – and asked Bill to hit the

bells and so he was hitting them all and Dick said he should

share and Bill said no he asked me so Dick called a meeting and

Bill said he couldn’t take the conflict and started sitting in

Mill Valley except for Saturdays.

MD: It didn't happen immediately, the changes to ZC when

Dick took over, but you just look around, from that point on he

changed everybody's consciousness about what we were doing, what

could happen, what was going to happen. Plus we're getting

Tassajara next month, then we're going to do this. He had

a whole agenda.

DC: I heard Dick talk about Timothy Leary once. He's

sort of like Leary. He said a lot of people had taken

psychedelics, not millions, but many people had had psychedelics

of different types. Leary thought LSD is going to change

civilization as we know it and helped to make that happen.

This entire vision came with it. Terrence McKenna

(mushrooms) said Leary is a completely unspiritual person.

MD: He just saw it as a chemical aid to living. He

wasn't thinking about spiritual things.

DC: To me he was somewhat. I read Leary's stuff

before taking LSD, and I considered him to have a very

responsible attitude. Fast, meditate, prepare yourself,

have a guide, take it, and go for the clear light. That's

the way I took acid. I thought that was great

advice. And Richard Alpert, the spiritual one, was telling

people to just take it and not be afraid to go romp around and

have fun. Anyway, that’s the impression I have.

So Dick got that job. He realized he had a hot product

there.

MD: He realized there was potential there. He was a

great organizer ?? the poetry conference at UC Berkeley.

That was right down his alley. If he wasn't doing what he

was doing he'd probably be president of GM or something.

DC: Movie maker. That's what he told Bob Beck he'd

like to do.

MD: I've spend years defending Dick in various ways.

Especially after the great debacle. A lot of people think

he's some horrible rapacious person, which he's not at all.

DC: He's got his problems but ?? he's still doing that Zen

thing. Ananda says Dick got exactly what he wanted.

He said Dick always said he didn't want to be head of a large

organization like Zen Center. He just wanted to work with

a small group of people. That's what he's got now.

MD: Better for him. I think that's what he

needed. But he thought he wanted a giant ?? Green's and

all ?? and he was socializing so much. It was getting

ridiculous.

DC: I feel that his socializing was part of his vision for

world change. That he basically wasn't that much of a

social person.

MD: And when Brown was in on all that it was hard not to

think that if you weren't there you were not at the center of

things. When the Governor was coming around, it was really

looking like this is it.

DC: It really had a strong element of hubris: pride

cometh before a fall. It got top heavy.

MD: He got caught by it. My feeling was that when

they called him on it, eventually, he was surprised. He

was rocked by it. Like he had no idea what he was doing.

DC: His life style had diverged so sharply from what he

was encouraging people to do in his lectures and dokusans.

It was unsupportable.

MD: It's interesting, knowing him so well, that he had to

go through all that. Very heavy stuff. And come out

where he is now. I think he had to just cut of everything

here. He just felt that all that was gone or lost.

That everyone in California thought he was horrible.

DC: He thinks that the only reason for him to come to

California is so people can throw tomatoes at him.

MD: We aren't talking about Suzuki. But we are in a

sense, because everyone sort of wonders, why did he pick Dick?

DC: That is a frequent question. Some people will

say it was a mistake.

MD: I feel the same way you do. I have a feeling

that he wanted to do it. He was there. He's

smart. He has a good understanding. Personally, I

think he did a lot of great things.

DC: He was part of a great period of experimentation.

MD: He made this whole thing happen which is still going

on. If all this hadn't happened, I wouldn't have Green

Gulch to go sit at right now.

DC: I'm looking at Suzuki Roshi's life. What did he

do in Japan? When he died he left all these places.

But it's not just him. It was him interacting with America

and some particular Americans and what happened there.

Without Dick and Graham and you ??

MD: I don't think Suzuki was ambitious for all that

stuff. I think he had some feeling about having a

monastery. I think he had a humbler vision. He

seemed so unambitious most of the time. He seemed

ambitious in an inner way. If you were there as his

student ?? and he would accept any student ?? he would be

incredibly sincerely open and involved with that person in a

real way. He would be there in every possible way for that

person. That's pretty ambitious ?? spiritually

ambitious. But not in the sense of getting bigger.

More like deeper.

DC: But the time at which he arrived, '59, giving him

until '66 to improve his English and get a good base ??

historically what better possible timing could there have

been. The time was one of enormous curiosity, looking to

the east, looking to non?materialistic practices. Maybe if

Dick hadn't have been there, the nature of the situation, there

might not have been a real impetus to achieve that level of

activity.

MD: Something else would have come along. I remember

we did the Zenefit to raise money. Big Brother, Gary

Snyder ??

Side A, Tape 1 ends.

Side B.

DC: Alan Watts gave a great talk.

MD: Suzuki walked forward on the stage and just opened up

his arms like that. Do you remember that? There was

a great cheer, a great yell from the assembly. He just

smiled. Just opened up his arms like that and just

radiated to everyone. It was like the guru ?? people were

eating it up. It went along with the music and the whole

consciousness raising thing. Everything that was going on

at that time. I don't remember him saying much of

anything. He might have said a couple of words. That

was the event. When he was actually up there in this rock

and roll situation doing that. It was surprising for me to

see because usually we would just be alone at Sokoji or

something.

DC: The other time I can think of was the big Be?in where

he sat up on stage with Alan Watts ?? Ginsburg. I remember

going with him, and I think it might have been Loring Palmer who

took him. I think Dick took him on a peace march once.

Do you remember him talking about Japan? Or telling about

important childhood experiences.

MD: One thing he said about Japan ?? He said in Japan we

just accept our role, what we're doing, and we tend to just do

that. But in America everybody thinks they have a choice

about everything. If I don't like this, I can do

that. He was talking about it in relationship to the

practice of Zen, that it caused us some problems, because it

kept us from committing. We always thought, well, if this

doesn't work out I'll just do something else.

DC: I've never totally accepted his trip on that ?? or any

Japanese person's trip on that because it's so strong.

It's a clash between Japan and America, not just Zen and

non?Zen. I was talking to Hoitsu about somebody that

wanted to get transmission from him. I was presenting it

to him in a non?prejudicial way. And he said, "Let them

get transmission from Mel or Reb or Les or Bill." And I

said well this person is sort of a peer of those people, and was

very close to Suzuki (his father) and that's why they're

interested. And he's not on particularly good terms with

those other people. And he'd say, "God, you Americans are

always talking about 'my way,'" My way is this, my way is

that. I want to do it my way. In Japan nobody thinks

about my way. There's the stream of practice of Buddhism

that we throw ourselves into. We follow THE way. It

really upset him.

MD: There's something about the spirit here that induced

him to stay here and start practicing with people here.

Something about the openness that he appreciated and wanted in

his students. He said a lot of the Japanese people here in

America ?? he was working at Sokoji as their priest ?? are not

interested in sitting. In Japan nobody's interested in

sitting anymore. That's why he was here. He was

interested in practicing, and he wanted to be with people who

were interested in practicing.

DC: He would go back to Japan and tell them that Americans

are great and really sincere and want to practice and are

interested in Buddhism. Even now in Japan ?? older guys I

was interviewing about Suzuki ?? they would say, "In America you

practice Buddhism with your head. Here we practice with

our body." They come with this superficial dichotomy

trip. The same things we used to think back in the

sixties. East inclusive; west dualistic. East

both/and; west either/or. They tend to do that. They

have a lot of set ideas about that. They tend to think

that Americans can't study Zen. There's no way to get

ahead in a Japanese system. People who go from here to

there to study anything will study awhile, but ultimately it has

to do with being Japanese and almost nobody gets anywhere with

anything they do. He was not unique, but rare in his

ability to leave his culture behind and work with

westerners. As far as Ananda is concerned, to transcend

Japanese Zen.

MD: Being willing to change it. Although he seemed

very faithful in many ways. At the same time it was

changing just to fit us. To make is understandable,

workable, practical.

DC: I think he had to continue to stand in the robes that

he'd grown up in and in the Buddhism that he'd been

taught. He couldn't go too far astray.

MD: He said it was important to have rules. A lot of

Americans' idea of freedom is no rules. He wanted to

disabuse us of that idea. So he had to emphasize quite a

lot in his lectures that rules were important. The rules

in practicing Zen are not just to have for the sake of rules,

but are the way that we become free. You can turn somebody

loose on the piano, and they can think they're very free, but if

they don't know how to play the piano they're not going to be

able to play music.

DC: Witness your painting. It's about following

rules that you create something beautiful, wonderful to look at.

MD: The freedom comes within the form. Americans,

especially young Americans at that time, had some problem with

understanding those ideas. Why do we have to sit hour

after hour in this rigid position?

DC: And then later when we got Tassajara, why do we have

to go to bed at this hour? There were a lot more specific

things where you were being treated like a child. To me

being treated like a child is a typical thing of Japanese

culture. And then you can have your freedom. Like in

art, they teach you exactly how to do everything, and all you

can do it copy everybody and do it the way they've been doing it

??

MD: That's interesting. The idea is that if

everybody does the same thing then you can see how everyone is

different.

DC: At a certain point you can go off and be free.

There's abstract calligraphers and everything happening in art

in Japan. But the road to getting to that level ?? once

you're up there there's no restrictions at all.

MD: Often those people are doing something that looks very

traditional, but if you know the tradition, and know the other

artists who are masters, you can see how different they are from

one another. Like playing shakuhachi. I've been

studying that for five or six years now ?? learning how to read

the music. At the beginning you just have to play those

notes one after another, and it's rather a difficult instrument

so there's nothing else you can do. You can't even get a

note out of it for awhile. Eventually your breath becomes

more and more efficient and you get stronger, and then you can

start doing more expressive things. You just play the

music the way it's supposed to be played and you will be playing

it in a very personal way whether you're trying to or not.

Everyone has a different way of breathing and a different

approach. It's our nature.

DC: I used to write a song every day. At least

one. If I felt like it or not. One of the ways I'd

write a song is I'd hear something I really liked and I'd try to

write something just like it. Invariably I'd come out with

something that was to me better than average and different from

what I was trying to copy. I found that to be a really

good way to do something. I was just reading something

like that too. Somebody ?? Mark Twain or Oscar Wilde or

somebody ?? saying that if you have the creative urge that it

can't be taught or learned, it's just there. and it can't

be suppressed. The person with the creative urge would

create original things ?? all you have to do is let them

go. Tell them to copy other things. It doesn't

matter. It will come out. I've always tended to

think that everybody has creativity.

MD: That's more Buddhist idea about it. As opposed

to this idea that we have more or less of the genius, or the

gifted ones, the inspired one, who is different from everyone

else.

DC: At least in Japan they have this idea of the national

treasure ?? the great Zen Master, the great poet, the great

artist ?? I almost feel that we have ideas here of

limitation. Their idea over there is that you're

unlimited, it all depends on how much effort you make. We

have the idea that you're born with a certain amount of talent.

MD: In Japan it's like the genius of effort. It has

the genius for putting out extraordinary effort. That's

why so much is achieved. I sometimes think about art in

general and people who are create ?? it has to do more with

sticking to it and going on with it. Whatever the ability

is in a person that allows him to become involved more than some

talent for putting the paint on or whatever ?? that that's the

most important thing.

DC: That's the 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration.

MD: Well, that's not right either. In music there's

undeniable talent that comes out in people at young ages.

There is something called talent and it's undeniable. But

at the same time there's this other thing where a person who you

might not think has a lot of talent has a lot of interest and a

lot of something that leads him to produce some very interesting

stuff. And then there's the person who has only the

willingness to work and no talent at all and no matter how hard

he works never comes up with anything.

DC: It's hard knowing the laws of art. How much is

nature, how much is nurture, how much is effort. I can

remember, in terms of music, having definite ideas about what I

liked and what I didn't like as far back as I can

remember. 4 or 5 years old. Stuff my mother

played. I didn't like the schmaltzy crap. I didn't

like overproduced band music that was too undefined. I

didn't like things that were too silly. As far back as I

can remember just from what I heard I had definite tastes.

MD: I liked Leadbelly more than Glenn Miller.

DC: Although I liked Glenn Miller. I tended to not

like big band stuff as much as ensembles. I'd like a

string quartet better than an orchestra. I had a definite

taste. In movies, songs, rock and roll. Almost

genetic or something.

MD: Getting back to Suzuki. Somebody told me that he

was always taking millions of naps. Have you heard that

much? A lot of naps in the afternoons. In the early

days, even before he was sick. Maybe he needed to.

Not that there's anything wrong with it. I suppose us

Puritans here in America might think you should be working or

something. He seemed to be free from those kinds of petty

ideas completely. Simultaneously, he was very free and

relaxed. At other times he would be somehow evoking this

incredible effort ?? from you and from himself. But he did

seem very relaxed most of the time.

DC: Terribly relaxed. Terribly at home with himself

and the world. At ease and comfortable to be with you

whoever you were. And he did take naps. But he’d get up so

early.

MD: One time I took him over to some lumber yard ?? some

big work yard in San Francisco. We drove into this place

and we went into this little house where they hang out.

There were 3 tough working men in there. They were talking

about football and swearing and carrying on. Suzuki just

swaggered in there and started talking about football. He

had his robes on. I'd never heard that tone of voice

before coming out of his mouth. At some point they started

looking at him, like, who are you? We somehow got our

boards and left. I remember watching him another time ?? a

woman came in and did tea ceremony for us. She did about

20 or 30 teas. It took like 3 hours or something. We

were just sitting there watching her. At the very end he

said, "Instant tea." While the woman was making the tea he

was watching her in zazen position, and he was so into watching

her. His hand would be moving a little with hers. He

was totally out there. Interesting to watch.

I remember him

talking about his teacher sometimes, and the tremendous feeling

of gratitude he had to his teacher. Not his father, but

his teacher. He told when he realized ?? a story about

when he did something that was unthinking and unconscious.

It was his monkey mind showing. He was so ashamed of

that. At some point he realized something ?? had a

powerful realization ?? and felt this overwhelming feeling of

gratitude toward his teacher. Tears were coming out of his

eyes and his nose and his mouth. He finally realized what

his teacher was trying to do. Why his teacher had been

hard on him at times. What his teacher had given him.

DC: I don't want to sound too cynical but I really think

the Japanese are programmed to have that experience. I've

heard so many Japanese people tell me ?? one of Suzuki's kids

will tell me about their experience with him ?? which wasn't

much fun. He was aloof and busy with other people and just

barked at them and didn't pay any attention and never touched

them and didn't listen to them and left them. His first

wife was murdered by a monk whom he insisted on keeping in the

temple. But they all say, I'm so grateful to him, cause I

realize now that blah blah blah.

MD: Do they have to tell that to themselves to make it

alright?

DC: They rationalize everything bad that happens to

them. Every hardship is rationalized in terms of a kind

teaching. (In looking at Suzuki's teacher) ?? I can't see

much there. Sort of strict disciplinarian. I don't

think he taught much zazen. Just doing services and being

a temple priest. It's great to be able to squeeze the good

out of things.

MD: I certainly had the feeling that it was more than that

the way he described it. When you look at Suzuki, if you

knew him, you had to feel that it was more than all that.

His teacher must have been something special ?? someway.

DC: I'm not convinced that So-on was so special. I

think Suzuki was special . . . Do you think that for Suzuki to

be special he would have had to have a special teacher?

MD: I don't know. If you look at it traditionally

you'd have to think so wouldn't you? Otherwise he'd be

like that farmer. That farmer Zen master who doesn't know

he's a Zen master, and if you say he is, he would say he was

not. To actually become a teacher in a formal sense and

take students, especially as a Japanese, you need certification.

DC: But you can climb on the shoulders of your

teacher. You can be greater than your teacher. Dogen

said that his master was the first truly enlightened teacher in

500 years. So he would have to have been more special than

who came before. So-on was a guy that yelled at the

neighbors and intimidated people around his temple. He was

a feared person. He was a fierce landlord. The

temple owned a lot of land and there were a lot of farmers on it

that had to give a percentage of what they grew to him. He

looked at it and said they weren't giving enough. He was

like a feudal landowner. He was taking care of the

temple. But the temples were important institutions that

had land, and were supported by people. The temple priest

was a great person, someone you would look up to, somebody above

the other people. This was broken up by the government

after the war – and before the war too. Buddhism was

suppressed during the war because Shinto became stronger.

Shinto was more in line with the goals of the militarists.

They were drafting the priests; Buddhism was on a

shoestring. It didn't have the nationalistic possibilities

that Shinto did. After the war they took land away from

the shrines and temples both to sell them to the people

cheaply. Buddhism lost out there too. It seemed to

me that So-on's reputation is one of being gruff and

aloof. Suzuki was aloof with his family but friendly with

neighbors and members of the temple. Everybody liked him.

He had a strong social conscience and at least after the war

talked about peace. And before the war too. He started a

kindergarten because he wanted to help revitalize the culture;

to get kids into a Buddhist school.

MD: I see him almost as a kind of adventurer.

Someone who was willing to leave his wife and children and come

over here; call them up and say he's not coming home. He

had the ability to go as far as he had to go to accomplish what

he wanted to accomplish. He wasn't restrained by any

bourgeois concerns. In that way he seemed like an

artist. He would say things that art and religion are the

deepest expressions of human nature. Art was right in

there. He had a tremendous respect for art and the people

who made art. So even if I didn't want to become a gung?ho

Zen instigator or organizer, I felt that I was still OK with

Suzuki because I was an artist. I never got any message

from him of, "Why don't you stop painting so much and come over

here and help run Zen Center?" I never got that feeling at

all.

DC: I think he was an adventurer. It's hard to see

that when you look at him in Japan because it's hard for anybody

in Japan to do anything but their duty.

MD: That's why he wanted to come over here too, so he

could be somebody different.

DC: He tried to get out at other times. He tried to

go to China during the war. He went over there and had to

run back.

MD: So there was something about him that was out of the

ordinary as a Japanese, and among Japanese that led him to want

to come over here and change himself.

DC: I think he was out of the ordinary in that he wanted

to get out and go somewhere else. There's so much security

in being Japanese ??

MD: Why did he want to do that? He wanted to explore

different parts of himself.

DC: I think that's true. The idea that Suzuki Roshi

was a great person in Japan, who had a great enlightenment and

great enlightened teachers, and wanted to bring those great

enlightened traditions is so romantic or something.

MD: But when he came over here there was nobody.

DC: He didn't have any students there. Ananda said

that the only time Suzuki got mad was when he said that to some

younger students at Zen Center. Suzuki called him up and

said, "What's this you say about I didn't have any students in

Japan?" Ananda said he was just repeating what Suzuki had

said. But he was sensitive about that. And his son

makes that point so strongly to me. Politics.

MD: So he was totally free when he came to America from

all that hierarchy. He would bring Japanese people

over. Or he'd go over and check in with them. Let

them know what was going on. But then he'd come back here

and do his own thing.

DC: There's another thing that affected his life more than

the hierarchy. He was head of an important temple with 200

sub?temples. He had 500?700 families, and that's what took

up his time. He was pretty free from hierarchy because

they have a pretty loose system. He hadn't chosen to be

involved in the big systems of headquarters in Tokyo. But

the amount of time he had to spend taking care of temple

obligations with these families was prohibitive. Non?stop

funeral, memorial services. That's what he wanted to get

away from. I only heard that from one person in

Japan. I had to make an appointment with a neighbor of the

temple through somebody who lived across town because the Suzuki

family didn't want me to talk to the neighbors. I had to

talk to the neighbors going around their backs. I'd tell

them I was doing it. They'd say, don't disturb the

neighbors. They're so nervous. I love Hoitsu, I love

his wife, but if you get out of their stream of things, get out

of what's accepted, it starts making them nervous. This

guy who lived below the temple said that Oh yeah, he used to

come down here all the time, sweeping the road, he'd come down

and tell me, "I've got to get out of here."

MD: So if you see Suzuki coming from that, coming over

here by himself with the excuse of taking on a small Japanese

congregation, and then getting involved with all these hippies,

and ending up on the stage of the Avalon Ballroom with Janis

Joplin ?? that becomes an interesting image. It makes him

look like a wild west cowboy. I would assume that would be

pretty damned radical to a lot of old priests back in

Japan. Unimaginable. That's how he's an

adventurer. Like these guy who decide they're going to

kayak down the entire west coast of the United States.

DC: Mitsu, Okusan, talks about hippies. What was the

sociological breakdown ?? you say there were 15 key people ??

would there be 5 or 10 coming and going?

MD: When we were pretty filled up there was about 10 and 4

or 5 in the back ?? usually anywhere from 2 to 10 other people

would be coming and going ?? or more ?? and more who would just

come to lectures. There might be 40 or more at lectures.

We started taping the lectures at some point. I remember

going through that routine. I don't remember what

year. Before '66, I think. Dick could tell

you. [July 1965]

DC: Dick and I are on good terms. He's really into

this. He's already outlining my book – suggesting

things. We're closer now than we ever have been. He

appreciated the support ?? Dan Welsh and me going there during

the first practice period. I just sent him the definitive

pictures of Suzuki's father and the guy before that. That

was a painting. The others were photographs.

Reproduced for the book, for Zen Center. I also got their

photo albums from Japan to America and had the best pictures all

photographed.

MD: I always did have the feeling that there was a hidden

part to Suzuki. Something mysterious. Where it was

all coming from seemed mysterious. He had so much

commitment and drive of a certain kind. Unusual. So

you couldn't help but think where does he get it?

DC: He was always there. If he wasn't sick he'd be

at zazen.

MD: He seemed constant, but not in a negative sense.

In a sense of faithful to something. He would often talk

about the inmost request. Remember that? That we had

to listen to and respond to our inmost request. It seemed

he did that in some way. My experience, during sesshin, of

people, of layers, was getting down to something like that,

where the sincerity of that the meaning of it, became uppermost

in your mind or your feelings. The depth and the levels of

that that seemed possible in his presence seemed almost

limitless. I sometimes I wonder how much we project our

own best nature into all this though. That's part of the

game, I guess.

DC: I'm not a firm believer in there being some truth,

like one truth and one story, to Suzuki, that I can look

at.

MD: I think you should be doing the Rashomon approach

here.

DC: That's exactly what I see. What type of book do

you think would be best about him?

MD: I think just that would be fascinating: to have

everyone's point of view, and just put them all out there and

let the reader draw his own conclusions. What else is

there?

DC: Dick could do a book that was his point of view.

And I think he should. And he can have a say in this

book. I'm going to do it the way Japanese bring things

into their culture: they don't homogenize them. They

don't stir things up. Everything's separate. So you can

see Dick as Dick, Mike as Mike, etc.

MD: And not try to cross?reference all this stuff and

correct everything for them. Even if there's actual

mistakes in there, you could just let them stand I

suppose.

DC: I could throw in a correction right after in

parenthesis.

MD: It's appropriate for a book about Suzuki, or anyone

like that, to have all these different points of view.

It's so Zen that way, so appropriate.

DC: I pretty much have to because I don't have opinions

about a lot of things. I don't want to have to be

sensitive and profound about a lot of things that I don't feel

that way about.

MD: I think that'll be fascinating, to hear everyone's

feelings and thoughts about it.

DC: Michael Katz, my agent, and I are talking about this a

lot. There is a strong contingent that wants a straight

biography where the process is invisible. I'm willing to

try that. And I don't mind trying it as part of the

process of doing it, but I think it would be pretty boring.

MD: I think if you work the biography into this thing,

then you could have both. That would be the best. If

you try to be as objective as possible about laying the facts

out about his life, then we can all draw certain conclusions

from that that are different from opinions. If you know

these are facts and you put them out there without

editorializing too much about it, then we can draw a lot of

conclusions about him just from those things. That he had

all these commitments in Japan and then he came over here.

Those are facts. There are conclusions that most of us

would draw from these various facts.

DC: There were commitments to the Japanese congregation at

Sokoji that it didn't bother him at all to drop. [I don’t see it

that way later] He and Katagiri both resigned and went over to

Page Street.

MD: It wasn't a huge group there. They could easily

get somebody else. He didn't have any problem with that.

DC: Did he ever disappoint you in any way? Were

there ways that he didn't come up to expectations?

MD: Sometimes I would think he was rather

buffoonish. He'd act clumsy sometimes. Not in a bad

way. Nothing that worried me. One time when I told

him that Trudy had died (in the hospital) ?? I think perhaps I

should have called him before she died, or at the time she was

dying, if that would have been possible. I didn't know

when she was going to die. I think he might have liked to

have been there. When I told him that she had died he was

very emotional on the phone. It almost worried me.

But when he came to the hospital he was completely in control

and more his usual self.

DC: How was he very emotional?

MD: His voice was cracking with emotion. He was

making a very obvious effort to control himself. I'd never

seen that side of him before. It disturbed me, because I

didn't know he was like that. A picture that goes with

that, is a picture of him later, sitting on the altar, and

separating her ashes with chopsticks, one by one. Part of

her ashes went to Wyoming and part stayed here. He looked

at each one and would say, "Beautiful ashes."

DC: Is there anything else you could say about Trudy?

MD: Her working on Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind was a very

satisfying thing for her to have been able to do, the kind of

thing she always wanted to do. Her philosophy had been

leading up to it, and her interest in writing and everything

else. It all came together with her intense interest in

Suzuki and Zen. She had a chance here to accomplish this

book which has grown on to be a very significant thing for a lot

of people. She did it right at the end of her life.

She and Suzuki became quite close. That's probably why he

was so emotional when she died.

DC: He said at her funeral he'd never hoped to have that

good a disciple.

MD: She had a real way?seeking mind. Even before she

met him she had that very strongly. When she was young she

had . . . quotations from thinkers and writers ?? trying to

distil everything down to some truth. Then her study of

philosophers. It all went to Suzuki. I encouraged

her a lot toward Zen and awakened philosophy. . . .

DC: The idea of philosophy for me is so boring and

tedious.

MD: I used to know some of these guys in Berkeley.

They were pretty . . .weird. There was one of those

guys that Suzuki told us about, he was going to commit suicide

over there ?? I don't know if he did ?? mad philosophers getting

so overwrought ?? trying to figure everything out would put you

over the edge.

DC: In my particular case, I tried to read philosophy in

high school, college, I just couldn't follow it. I'm

just not constitutionally capable ?? something about attention

span ?? but when I read Zen stuff...

MD: Dick used to be interested in some of that and he would talk

to us about Heidegger. Dick would get a Heidegger book and

skim it or get a summary, and then that was Heidegger.

Trudy would consider that very half?baked understanding.

DC: I admire somebody that can skim it or read a synopsis

and come up with a little world?view ?? I couldn't even do

that. I'd forget it. Way?seeking mind ?? he used to

talk about way?seeking mind. It would be interesting to

make a list of key things he would bring up like way?seeking

mind, grandmother mind . . .

[Tape 2 Side A]

DC: Grandmother mind was his interpretation of kind mind,

one of Dogen's 3 minds in his Tenzo Kyokun, instructions to the

cook. I felt like I had complete permission not to get

involved with the complexity of things. Not to have to

figure out what all the philosophers said. Not to have to

even figure out what Dogen was saying.

MD: You'd just get hung up on it. Why bother?

DC: I really wasn't interested. I did, however,

study Dogen and Sandokai in Japanese and I studied it with

Suzuki and other Japanese priests. But I was just doing it

for something to do.

MD: Remember when he would be expounding on the Blue Cliff

Records? Bru Criff Records? That could get a bit

tedious, I must say.

DC: They're thinking of publishing the Sandokai

lectures. There are disagreements if it should be done or

not. Peter Schneider pointed out that his lectures on

particular texts were not as interesting as the general

lectures.

MD: He'd get sort of technical. You'd have to

interpret everything. It seemed so obscure to us.

He'd have to go to great lengths just to make it barely

understandable. Then he'd start talking about what it all

meant. Seemed kind of tedious. But he always ended

up making it kind of interesting ?? at the end. He seemed

very interested in it all. He had a side of him that was kind

scholarly.

DC: Definitely. He studied with Kishizawa. But

the more I look into it in Japan, I can see our tendency to

exaggerate and idealize things. Some of that comes from

Dick. Dick is Zen Center's primordial exaggerator.

MD: He's a mythmaker.

DC: Right. The idea that Suzuki was a close disciple

of Kishizawa Roshi? not quite. So-on Roshi was his first

teacher and Kishizawa was his second and he worked closely with

him and studied with him for thirty years but he wasn’t a

disciple. He'd go once a month and hear a lecture. I

think Suzuki was important to Kishizawa. They did big

ordinations together ?? 400 people at a time. They were

revitalizing Buddhism. He was inspired by Kishizawa.

He was more than a scholar. He was a Shobogenzo

scholar. But also he was into zazen and practice with an

emphasis on Sandokai. He's got 300 pages of lectures on

Sandokai. Sandokai is the meaning of unity and

multiplicity. We chant the text at Zen Center. It

came in in 1969 with Tatsugami's arrival. I think there's

stuff in there of interest. But I think it would be a

great disappointment to bring it out the way it is edited at

this point.

MD: Regarding Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind: I was busy

making my paintings. I was not so involved. When we

moved to Mill Valley we stopped going to zazen every day like we

had been in the city for years. I was getting more into

art and less into Zen at that point. She and Dick would

meet and talk about it. She would work on it. She

went over the original tapes to some degree. She would

talk to Suzuki a lot about it. She talked to him about

particular points in the lectures she wanted to clarify.

She went non?stop on it with a real intense interest and

involvement.

I'm pretty sure that was when were when we were in Mill

Valley. She already had cancer and didn't know what would

happen next. Hoping it would go away, but it was slowly

getting worse. She had breast cancer. She was going

through intense stuff ?? my trying to help her by fasting and

being very thin. Diets. Eventually the

hospital. I tried to keep her out as much as possible as

she preferred to be out and could do more things. But it

got more and more painful. I don't think she was into all

that when she was working on this. She had a

respite. The book came out in '70 and she died in '69.

So she was working on it in '68 and '69 probably. My

memory for dates is real bad. I don't remember her talking

to me a lot about it though I'm sure she did talk to me about

it. I don't remember things like that very well. It

was very satisfying for her to do the book and it brought her

closer to Suzuki. I remember being at Tassajara when she

was quite sick. She had trouble moving around. We

were all in Suzuki's cabin. She was lying there. She

seemed very happy to be there, with him. He seemed happy

to have her there. That was just at the end. I on

the other hand was getting kind of weird dealing with it.

I was getting fed up and impatient. Emotionally confused

about a lot of things that were going on. Difficult

time. She seemed quite calm. The whole experience

was rather intense and quite inspiring. Interesting.

DC: Did Angie come here?

MD: She was in Mill Valley. She helped take care of

the kids. I sent the kids back to my parents at one point

because it got impossible and they were willing to take them on

for awhile. Then Angie and I just took care of Trudy

together. Eventually just me. It took quite a lot of

doing ?? cooking and carrying her around a lot to various

events. Carrying her out to the car and carrying her into

a restaurant and stuff like that. She got lighter and

lighter. But her spirit was great. She became a

lightning rod for a lot of people. People would come

around and get whatever they got out of the experience. It

would happen that people would bring a lot to it. She

could just be herself, and they would take something away from

it. She wrote quite a lot of poetry toward the end of her

life which was quite good. I've got it someplace.

Maybe you can look at it.

DC: One thing I've got in mind is archiving, so that has

no limits to it. Something like that would be good.

MD: That would be good to get out there in some way.

Some of it's really good.

DC: Zen Mind Beginner's Mind is the magnum opus of Suzuki

from one point of view. Everything he said that's recorded

can be divided into Zen Mind Beginner's Mind and everything

else. That's a lot because of Trudy's work. She did

a great job. Everybody wants to come up with a book that

other people love. There's hardly anything like it.

MD: I've met people from time to time who have told me

that the book has saved (seized?) their life. And twice my

son Will had been trying to get into college, or something, and

Zen Mind Beginner's Mind will come up and he's had the

opportunity to say well my mother edited that book. We

can't help but think it helped Suzuki to accomplish what he

wanted to accomplish.

DC: Definitely in this book I should tell the story of how

Zen Mind Beginners Mind came about, so any details that could

make that story more interesting.

MD: I think Dick could give you the best information on

that.

DC: Here's a Dick story: Why did Tassajara come

about? Well, Suzuki's original idea was that everybody

would just have their jobs and come sit at Zen Center and

practice in the city. But he was disappointed because

nobody but me got it. That's Dick's explanation:

nobody but he could practice in the city. And because

nobody could practice Suzuki wanted to find a place to practice

in the country. Not only does he say this now, he said

this back then. I almost think I remember him saying it in

front of Suzuki. Dick did a lot of outrageous things that

people didn't like him for, but he tended to do them in front of

Suzuki.

MD: To test things.

DC: He got a tremendous amount of support from Suzuki.

MD: But was it Dick's or Suzuki's idea to get Tassajara.

DC: Dick says it was Suzuki's, that he needed the place to

work with people closer because it wasn't working in the city.

MD: I remember hearing something to that effect.

That Suzuki did want something like Tassajara where he could get

away and work with people. I don't know much about

that. I was always trying to get away from having to take

a lot of responsibility at Zen Center. So I was just happy

to go mail out the goddamn mailers. Graham and I were down

there doing that. And I designed a couple of posters for

benefits.

DC: I have the impression of Graham having been somebody

that Dick modeled himself after.

MD: They were quite close. The story I heard from

Dick was that Graham was a hopeless alcoholic.

DC: I know Graham very well. I see Graham these days

and he is a hopeless alcoholic.

MD: At some earlier point in his life, before he got into

Zen, Dick said the doctor looked at him and just said, you're

through, you're dead, he was so bad. Then he became like

the drill sergeant. Graham was the toughest guy who never

moved and always sat in full lotus, back straight as a

ramrod. He was Mr. Tough Guy. That went along with

being an alcoholic. If you have that tendency, perhaps you

have to be extra strict so you won't start drinking. He

was a very inspiring figure. He seemed able to tough out

any sesshin without complaining.

DC: I talked to Graham recently. He lives in

Healdsburg now. I used to see him in Japan. He and

Dick were very close, but their relationship fell apart when

Graham went to Santa Fe to help him with the restaurant.

MD: I was there and saw them both there while he was

working on the restaurant. I saw them working

together. I didn't see any fights or anything.

DC: Dick would say that Graham was drinking too much to be

effective. Graham will say Dick was too crazy.

Graham would be happy to speak with Dick again, but there was a

definite falling out.

MD: Some people just change, like that, when they

drink. I've never been around Graham.

DC: He's not a person who has a radical change, but he

tends to drink a lot. It's amazing he's still

drinking. He was talking to me about dying. He felt

like his life was over about 6 years ago, he was so dissipated.

MD: That's so funny. You see a guy who seems so

strong in Zen, and then he's like that. He was making such

a big point about being tough. Too much. Interesting

to look at people and how they turn out. Suzuki told an

interesting story about ?? there's a group of people walking

along a stream. Everyone's looking for the best

pebble. Some people are up in front and they're searching

very intensely, running forward. But there are a couple of

guy in the back who are just enjoying the day, laughing,

talking. One says, "Oh, what's that?" And pick up a

pebble. He didn't want people to get caught by that and

try too hard. He looked the cucumber. His teacher

always called him the third cucumber ?? the one that's all bent

up.

DC: Crooked cucumber.

MD: Sometimes they also refer to it as third

cucumber.

DC: I plan to call the book Crooked Cucumber.

MD: And the horses. That's a great story. The

one that runs when he just sees the shadow of the whip.

The one that runs when he feels the whip on his skin. The

one that runs when the whip strikes him and the pain really

sinks in. The last horse only runs when the whip sinks

into the marrow of his bones. He would say that doesn't

mean that the first horse is better than the second horse or

that the second horse is better than the fourth horse.

It's all the same, really.

DC: I look forward to finding what lecture that's

in. In your life as an artist, is there anything you can

say about what you learned from him that you've applied?

And what you didn't learn? And what other things you've

learned since then? How does he fit into your life?

MD: I continue to sit. I've been doing that since I

started 30 years ago. I mostly sit by myself. I

combine it with shakuhachi playing, quite often.

Occasionally I go and sit with a group and recently I've been

sitting with Ed at Green Gulch, one?day sittings. I like

the way Ed has changed over the years, and I feel kinship with

him. He's very relaxed about everything. He gets

more out of people that way. I enjoy sitting with Ed and

the group that he has. A lot of beginners like to go

there. I mentioned earlier, before Trudy and I went to

start sitting, and just were going to lectures, in my own mind I

felt the words were ?? that I was going to blow over in the

first windstorm. That's the way I felt. I felt

vulnerable. I wanted to do something about that. I

wanted to feel less vulnerable and more solid, more

grounded. I wanted to feel less vulnerable to the

winds. My study with Suzuki and practice with him has made

me feel more rooted, more stable. I have quite a few

mental problems in my family. That might be part of my

desire ?? You read about people who got deeply involved in

spiritual communities, then wake up one day and realize they

have no life, no children, no wife. I'm glad that I didn't

(get so involved), because at a certain point I was really

torn. I couldn't figure out if I should be a full?time Zen

monk or an artist. I was having a terrible time figuring

that out. The life style seemed so different. One

seemed so strict, the other not. I was going back and

forth trying to sit on two chairs at the same time.

Finally I decided I should be an artist. As soon as I

decided that, everything got cleared up, and I didn't feel tense

any more. I was more relaxed about it. I could do

art first, and then I could sit. I could still sit.

The other way around would have been hard.

DC: There's something perverted about the idea of

full?time Zen. It's such a strong idea, such a strong

feeling that people have to grapple with.

MD: Or just helping in a community. There's a lot of

work to be done. Older people have to have all this work

to do for others.

DC: Is it for others, or is it for an institution that has

a life of its own? You have to spend all your time

updating the mailing list in the back room.

MD: But I'm glad that Zen Center's still around.

That I can participate with the group if I want to.

DC: It's a matter of balance.

MD: In the long run, my own life, meeting Suzuki and

following the way he taught me, has colored everything.

It's something that continues. I feel now that I'm getting

older, more the pull into practice. It's different

now. In many ways it's a lot easier to practice now.

There's so much baggage that's gone.

DC: I find that I have less frenetic energy.

MD: Yeah. Impatience, distractions. Much

easier to just sit there and have a little peace and quiet.

DC: What other things have you brought into your life

besides art and Zen? Have you been influenced by any other

teachers, teachings, readings?

MD: Other teachers would be art teachers. Fred

Martin was an important teacher for me, at one time the director

of the Art Institute. I haven't sought out other religious

teachers. I occasionally think about it. Sometimes I

used to sit with Mel, too. Sometimes I sit with Ed.

That seems what I'm looking for there. I don't feel the

need to search for other groups.

DC: Or there's the search for the great teacher.

Many people are doing that. There's a guy named John

Tarrant, a Zen teacher in Santa Rosa who's a really neat

guy. He's an Aitken student. He writes good

stuff. He's very clear. Andrew Cohen is interesting.

I’ve suggested they invite him to speak at Green Gulch.

MD: Michael Wenger was thinking about asking me. I

can't talk to a bunch of people.

DC: The reason I'm doing it, even though I don't want that

kind of role, is that I think it's good for it to be spread

around.

MD: You can do it too. You could always just read part of

your book.

DC: I don't want to do that.

******************************

Mike Dixon on the phone October 10, 1994

DC: (I told Mike of Ananda's point about Zen Center moving

from a loose lay community to a priest trip and Mike said that

that might have been Dick Baker's making as much as

anyone.)

MD:

"Without Dick, it might have stayed very much the way it was and

Zen Center might not even exist now. The year he became

president, probably 63 or 4 or something, I lost by one

vote. And he just started doing everything. He had

all these ideas and eventually I found myself (in 66) down in

the basement sending out 15,000 fund raising brochures to raise

money for Tassajara. Dick stated talking about how we could be

priests and we could be masters. He was the first guy to

have that idea as a possibility and we all thought he was nuts.

DC: "Did you see SR as having an unattainable status?"

MD: "Kind of. I don't think that most of us ever

thought beyond the fact that here he is and we're studying with

him. It's not like he was a God, but we didn't have the

idea that we could be like that, or something."

DC: "That's exactly the difference between Reb Anderson

and me. From the moment he arrived at Zen Center he was on

a crash program to get enlightened, be a priest, be abbot,

become a Zen master and all. I was there for a good

time. But Reb and Dick also had an element of devotion,

they were strongly devoted to Suzuki. Anyway, before I was

ordained, Reb brought me to his room at Page Street and lectured

me on taking ordination seriously, realizing that I was

embarking on a new course, leaving behind the lay world,

becoming a role model, an example for others. We were

worlds apart. I understood what he was saying but I had no

interest in it. Now I think maybe he was right. I

had no business being ordained as a priest. I was just

doing it to be closer to Suzuki, and there was that to it at

least at the first. But when I was ordained he was clearly

dying, Katagiri suggested we postpone the ordination, and I

strongly insisted we go through with it - I think that made a

difference as my fellow ordainees were less assertive than

me. I did not trust the future and I wanted the status of

priest, disciple of Suzuki sealed. So I was ordained