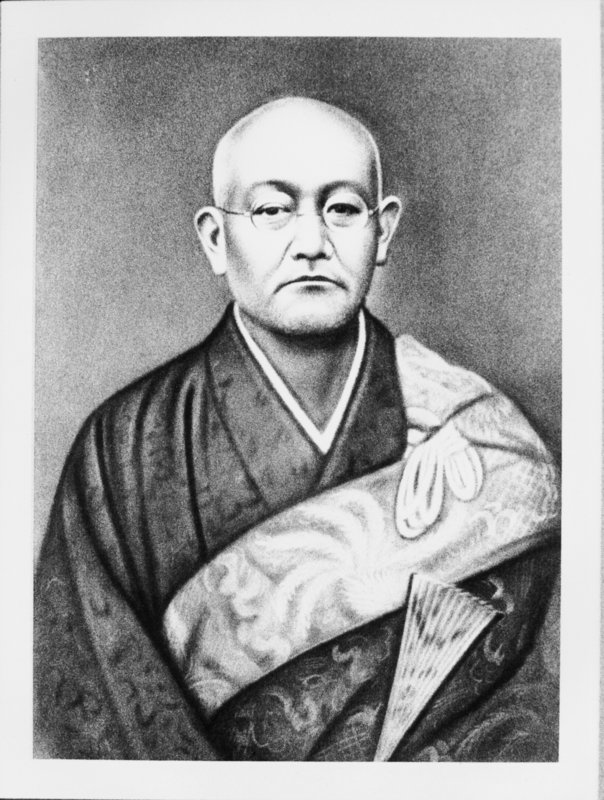

Gyokujun So-on

Gyokujun So-on was Shunryu Suzuki's master from whom he received dharma transmission. He was a disciple of Shunryu's father, Butsumon Sogaku and abbot of Sogaku's former temple, Zounin in Mori. Later he became abbot of Rinsoin. After his death Shunryu became abbot of both.

So-on was an orphan adopted by Sogaku. Thus he was Shunryu's older step brother. His birthday is unknown. I gather he died at 57 in 1934 so have called his birth year c.1877

So-on is mentioned now and then in Shunryu Suzuki lectures, usually as "my master" and most of the pertinent material from those mentions will be below in the Crooked Cucumber excerpts. A cuke goal to gather all such comments as well as those on other subjects will take time to realize.

Here's one story Suzuki told about So-on that wasn't verified until after the book came out. I knew it but wasn't sure if it was Suzuki's or Katagiri's until Dennis Samson mentioned it and confirmed it was indeed something that happened to Suzuki.

He was out working with his master, Gyokujun So-on on a bitterly cold winter day. They were cutting firewood. Suzuki's mind was wandering and he didn't notice as So-on pulled back the thin steel blade of his saw so that it bent into a U shape and let it snap onto the unsuspecting face of poor little Crooked Cucumber. It was an extremely painful bit of shocking feedback that Suzuki would never forget.

The nickname Crooked Cucumber was what So-on called his small, young disicple. Shunryu never used the Japanese when speaking to us that I know of. At first we thought it was magatta kyuri which is a literal translation and which Gary Snyder thought it to be and said he'd heard used in that way. But after the book came out, Suzuki's son Hoitsu told me he remembered hebo kyuri being used and thought that was it. The hebo kyuri he said it the tiny little twisted one at the end of a vine. It's useless. The word runt comes to mind. An online dictionary translation of hebo is "bungler, clumsy, greenhorn." At the memorial for Shunryu's little sister at the SFZC City Center, her widower husband said "Hebo kyuri," when we greeted. [page on this] - DC

So-on in Crooked Cucumber

I only searched for the word so-on for this collection. When Suzuki talked he would use the word master and sometimes teacher. So there may be some quotes from him in the book missed. - dc

Too much too put it all in here - 224 times the name So-on in the book - but one can read it all on cuke by following the text and links below.

From the Introduction

From the time he was a new monk at age thirteen, Suzuki's master, Gyokujun So-on Suzuki, called him Crooked Cucumber. Crooked cucumbers were useless: farmers would compost them; children would use them for batting practice. So-on told Suzuki he felt sorry for him, because he would never have any good disciples. For a long time it looked as though So-on was right. Then Crooked Cucumber fulfilled a lifelong dream. He came to America, where he had many students and died in the full bloom of what he had come to do. His twelve and a half years here profoundly changed his life and the lives of many others.

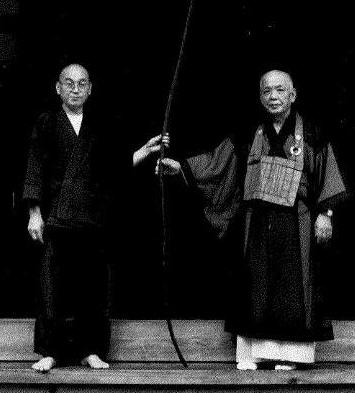

in photo -

Hoitsu Suzuki and Shoko Okamoto hold Gyokujun So-on's bow at Zounin in Mori where Okamoto was abbot.

Shunryu Suzuki said no one else could open that bow it took such

strength.

in photo -

Hoitsu Suzuki and Shoko Okamoto hold Gyokujun So-on's bow at Zounin in Mori where Okamoto was abbot.

Shunryu Suzuki said no one else could open that bow it took such

strength.

Part One - Japan

Chapter 1, Childhood

TOSHI HAD made the first two critical decisions of his life by age eleven: to become a monk and to leave Kanagawa. "My ambition at that time was directed toward a narrow idea of attainment, but I made up my mind to leave my home and to practice under a strict teacher." He had been impressed by a popular Buddhist belief that by being ordained one saves one's ancestors for nine generations back. But where should he go? With whom should he study? It was March 1916 and he had just graduated from elementary school.

This was the time when a boy's career was often decided, when he became an apprentice in a trade, began military school or some other training, or started working with his father in the fields. Very few went on to higher education, especially in that region. While it was normal for Toshi to follow in his father's profession, it was unusual that he decided to go far away before his parents were ready to let him go, not even choosing to start with his father and move on later.

While Toshi was considering these matters, Shoganji had a visitor, a priest who came several times a year to pay his respects to his master, Sogaku. Gyokujun So-on Suzuki, Sogaku's adopted son, had just become the abbot of Zoun-in, Sogaku's former temple. He was like an imposing uncle to Toshi--tall, tough, exuding confidence. Toshi was enamored with him.

I knew him pretty well and liked him so much. When I asked him to take me to his temple, he was amazed but said it would be fine with him. I asked my father if I could go to Shizuoka Prefecture with him. He agreed, so I went to my master's temple when I was thirteen.

Toshi was actually eleven, almost twelve, at the time. He calculated thirteen by the prewar counting method, wherein a person was one at birth and two on the following New Year's Day.

Although Toshi felt he was making these decisions on his own, discussions had been going on behind the scenes for quite some time. His intentions and those of his parents were in accord except for the timing. They thought he was too young to go and suggested he wait till the next year. But Toshi wanted to go right away. He pointed out that his father, Sogaku himself, had chosen to begin apprenticeship with his master at a young age. Toshi wanted to do the same.

It all happened so quickly that, to his sisters and half brother, it seemed he was being whisked away from the family. Sogaku and Yone did not want to spend the rest of their lives at Shoganji. It was right that So-on, as the first disciple, would inherit Zoun-in from Sogaku. If Toshi did well with him, he could inherit Zoun-in from So-on, and then Sogaku and Yone could retire there. If Toshi's father ordained him

and became his principal master before he left, then So-on would become his second teacher and Toshi wouldn't be in line to get Zoun-in. Sogaku was too old to train Toshi anyway, and many believed that a father could not properly train his son. As the proverb went, "If you love your child, send him on a journey." So Toshi went off with his first master, Gyokujun So-on, at the age of eleven.

Chapter 2, Master and Disciple

Chapter 3, Higher Education

From Chapter 4. Great Root Monasteries

SHUNRYU SUZUKI had thought that after Komazawa his training would be over and the world would be ready for him. He was, after all, an abbot with his own temple and had received transmission and recognition by the Soto organization. But So-on, the man of many growls and few words, hadn't mentioned that there was more training to look forward to--at Eiheiji in Fukui Prefecture, one of two daihozan, "great root monasteries" of the Soto school (along with Sojiji).

…

And when something was not done in the right way, there was always a senior to scold the offender. Shunryu felt their eyes on him when he walked in a room, checking him out from foot to head. It was not entirely new--he'd gotten the same from So-on--but it was no longer coming from one source. He was part of a larger team in a wider theater, getting the physical practice down with the precision of Noh or Kabuki performers. It was overwhelming, and after the initial nervousness and bungling, gradually it became harmonious and invigorating.

…

The priest whom Shunryu had been chosen to serve was Ian Kishizawa-roshi, considered to be one of the greatest Soto masters of the day. So-on had arranged this connection. A disciple of the

great root teacher Nishiari Bokusan, he had also studied under Nishiari's disciple, Oka Sotan, and had known So-on at Komazawa and at Shuzenji. He had also known Sogaku back in their younger days. He was sixty-five years old, thirty-nine years older than Shunryu and twelve years So-on's senior. He was strict and particular, but not mean like So-on. A highly respected Buddhist scholar, he had a cultured air about him. Like Oka he had continued the work Nishiari had started in Dogen scholarship and in 1919 had succeeded Oka and Kitano as the official Eiheiji lecturer on Dogen's Shobogenzo. Kishizawa saw great promise in Shunryu and kept a close eye on him. With Kishizawa, Shunryu found he had to be alert at all times--nothing was to be taken for granted.

…

HAVING COMPLETED two practice periods, each concluding with a seven-day sesshin, Shunryu told So-on he wished to continue at Eiheiji. Being there and attending to Kishizawa had opened his eyes wider. He realized he had a long way to go, and it seemed best to follow Dogen's way at the great temple he had founded. He told So-on that he would like to continue there, where he had found out what monk's practice is really all about. In particular he felt that his zazen had deepened. Though zazen had always been part of his practice, it hadn't been emphasized as at Eiheiji, where he sat first thing in the morning and last at night.

So-on let Shunryu have his say and then responded from an unexpected point of view. "Crooked Cucumber, you better be careful or you'll be a rotten crooked cucumber. One year is enough! I will not let you become a stinky Eiheiji student! Soon you should go to Sojiji," he said, referring to the other major Soto training temple. Once again Shunryu was crushed by So-on.

On the train back to Eiheiji, Shunryu replayed his master's words. He would have only two more months there, and those months would be on the relaxed summer schedule. Wistfully he remembered the year gone by as the train rolled toward mountainous Fukui. Being away had magnified how wonderful it was. There was

something of the stink of pride at Eiheiji, but there was also something of incalculable value. Yet when he was there, Eiheiji wasn't special at all.

…

ON SEPTEMBER 17, 1931, Shunryu took the train from Eiheiji to Sojiji in Yokohama, where So-on had arranged for him to continue his training. He entered tangaryo the next day. Located near the hub of Japan's growing commercialism, the atmosphere at Sojiji was softer, less lofty and medieval than at Eiheiji. Whereas Dogen was said to be the father of all Soto monks, Sojiji had been founded by Keizan, who was considered their mother. It was he who had brought Soto Zen to the farmers and peasants. As a result, Soto Zen had gradually become one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

While at Sojiji, Shunryu kept an eye on his temple. Commuting

to Zoun-in, he oversaw the construction of two additions: the Kannon-do, or Kannon hall, in which Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, was enshrined; and the seppin, a meeting room for guests and practitioners. There was a dedication ceremony for the additions in March of 1932. Shunryu's close attention to the well-being of his temple contrasted with his lack of desire to be tied down to the duties of a temple priest.

Soon after that So-on showed up at Sojiji. Shunryu told him that he was content with the practice and thought he could continue living there much more easily than at Eiheiji because of the proximity to Zoun-in. He'd been there half a year and was hoping to stay for a few more years. There was no thought of going abroad. He had a fully engaging life among likewise well-educated monks, some of whom shared his sincere devotion to realizing the heart of Buddhism.

After they'd been talking for ten minutes So-on said, "Maybe it is time for you to leave Sojiji."

Chapter 5, Temple Priest

SOGAKU CONTINUED to play a major role at Zoun-in. Shunryu was often away helping So-on at Rinso-in and had taken over So-on's positions in two large, well-known temples, Kasuisai and Daito-in, where his responsibility was to give lectures to unsui and lead them in zazen. Shunryu brought to his duties a youthful enthusiasm and an almost zealous devotion to the teachings and practice he had learned at Eiheiji and Sojiji. Uchiyama-san, a priest who was to marry Aiko, thought Shunryu was a terribly sincere priest, since he led zazenkai, the lay sitting groups, and said in his soft-spoken way, "We must keep Dogen's practice and encourage it so it will prosper." Uchiyama said it was rare for a priest to talk like that. Shunryu's style of speech was largely inspired by his continuing association with Kishizawa.

...

He had not wanted his relationship with Kishizawa to end when he left Eiheiji. Fortuitously, the great master's home temple had changed in recent years to Gyokuden-in, a small branch temple of Rinso-in located about three miles from Rinso-in. On May 1, 1932, Shunryu visited Kishizawa and, with So-on's blessing, requested permission to continue studying with him. Kishizawa accepted and Shunryu became his zuishin (follower), a name given to the relationship with one's second teacher. He would always be So-on's deshi (disciple), but he would later attribute most of his understanding of Buddhism to Kishizawa.

…

SHUNRYU'S DHARMA brothers Kendo and Soko were in charge of Rinso-in most of the time, because So-on was leading a practice period at a temple in neighboring Shizuoka. Shunryu arrived at Rinso-in early one evening to find that Kendo and Soko had gone out to a movie. He knew that So-on wouldn't like that and that his dharma brothers would not want to get caught relaxing by their fierce master. He lined up his geta, wooden platform sandals, at the bottom of the steps in the entryway in the spot where So-on, and only So-on, left his. When Kendo and Soko got back they were filled with terror at the sight of the geta until they heard Shunryu laughing from behind the shoji.

…

EVEN THOUGH Buddhist priests had been getting married since the previous century, it was still controversial. When Shunryu's parents were married, it was legal for priests to do so, but the prohibition against women being lodged in temples was still part of the Soto regulations when he was born at Shoganji. The teachers in Shunryu's dharma lineage didn't get married: neither Nishiari, Oka, nor Kishizawa. Though So-on had not officially married, Shunryu considered Yoshi to be So-on's wife.

…

IN LATE April 1934 So-on arrived at Eiheiji to assume the position of assistant director. He would be involved both with administration and with the training of monks. On his third day at Eiheiji, after lunch, he said, "I'm going to the toilet," then had a stroke and collapsed in the hall. From the Fukui hospital he was moved to Rinso-in for recovery, but his condition deteriorated. A week later, on May third, So-on passed away at the age of fifty-seven.

So-on had always walked with his head up and greeted people without looking at them, yet hundreds of laypeople and priests attended his funeral. His ashes were interred at both of the temples that he had run. Shunryu conducted the ashes ceremony at Zoun-in. So-on's new teardrop-shaped granite stone was placed next to Sogaku's in the abbots' line. During the ashes ceremony, chanting the Heart Sutra, Shunryu picked up some of So-on's bone bits with chopsticks and placed them in an opening at the base, then picked up a bamboo ladle and poured water over the stone. How many times he'd watched So-on do this--for eighteen years starting right here and ending right here. Shunryu had many memories of the man who, more than anyone, had molded his character. Never again would he be called Crooked Cucumber. He could not help noticing that he did not feel much at the passing of his master.

Yoshi did not attend the funeral. For a time she stayed at Rinso-in helping out and doing ikebana flower arranging. Once when Shunryu's mother visited, Yoshi went upstairs and hid. Then one day she had Soko deliver So-on's robes to Shunryu at Zoun-in. She moved out of Rinso-in and returned to her family in Mori.

The loss of Miss Ransom and his wife and the deaths of both his father and his master gave meaning to the age-old Buddhist teachings that everything changes and life is suffering. It was not just his own suffering and transience that he felt, but that of others as well, of all beings--there was no difference. Reflecting on his years with So-on and his time at Komazawa, Eiheiji, and Sojiji, Shunryu saw two big mistakes he had made. First, he wished he'd made a stronger effort. He could hear So-on's frequent admonitions to realize how precious the opportunity to practice was: "You should not waste your time!" At first he'd thought that meant he had to work all day and all night or, since he couldn't work all night, at least behave well all night. Later So-on had explained, "To understand Buddhism is not to waste your time. If you do not understand Buddhism, you are wasting your time." When he was a boy, it had seemed like some convenient logic and he had not felt encouraged, just confused. Now he was beginning to appreciate his master's words, if not his personality.

...

Actually, what we are talking about is that enlightenment and practice is one. But my practice was stepladder practice: "I understand this much now, and next year I will understand a little bit more, and a little bit more." That kind of practice doesn't make much sense. Maybe after you try stepladder practice, you will realize that it was a mistake.

He was beginning to see that he couldn't organize his practice, his life, the teachings he was receiving, and the lessons he was learning. He had to let go of all that and leave it to ripen on its own. He had to adjust minute by minute. He was getting a glimpse that the way is to have "a complete experience with full feeling in every moment," not to use each moment to think about the past or future, trying to make sense of it all. What he was coming to was not some mushy all-is-one-let-it-be approach. It included a view of oneness, but it also included the opposite--that each moment, each thing, is distinct and must be addressed mindfully, not with some vague idea of universal significance.

When he had first returned to Zoun-in to live, Shunryu discussed this point with So-on. He explained that he could accept that all things are one, but not that they are different. Yet in his studies he had learned that both were true. So-on had simply said, "Emptiness and existence--if you stick to either one you are not a Buddhist."

It is only because our life is so habitually and so firmly based on a mechanical understanding that we think that our everyday life is repetitious. But it is not so. No one can repeat the same thing. Whatever you do, it will be different from what you do in the next moment. That is why we should not waste our time.

Now that he had lost so much and been so changed, it was easier for Shunryu to give up his systems and beliefs and just be in the world, walking step by step with no person, thing, or idea that he could depend on permanently. He had his duties, his relationship with Kishizawa, his mother, his fellow monks, and some friends--especially Kendo and the potter Seison. But he wasn't so attached to anyone or so sad at his aloneness. His life would go on, and So-on's passing would lead to the next big step--and to a lot of trouble.

...

SO-ON'S SUDDEN death created a vacuum at Rinso-in. He had appeared to be grooming his nephew Soko to be abbot, possibly so that So-on could comfortably retire there, but surely also because Soko seemed to have So-on's administrative ability. So-on could have remained the abbot in absentia for years while at Eiheiji, without anyone worrying too much about who was running it in his stead. In that way he could have eased Soko into the position and slowly built consensus within the danka. But now the decision would be made by the board, which represented various factions in the membership.

An old priest named Ryoen Risan was trying to take over Rinso-in. He was a dharma brother of the former abbot, the one So-on had been asked to replace because the temple had been going downhill. Ryoen had strong backing among the danka, especially among a clique of local priests. At first there was no one to oppose him, so he started handling some of Rinso-in's affairs.

There were many danka who did not like the idea of Ryoen getting the temple back for his lineage. Some of these backed Soko to be the abbot. But he was still in Komazawa, hadn't received transmission from So-on, and was quite young. Also, Yoshi didn't like him, and she had some influence. She wanted Shunryu.

Before I took over my master's temple, I didn't cause any trouble. I was just trying to study. But after I determined to take over my master's temple, I caused various problems for myself and for others. There was confusion in my life, a lot of confusion. I knew that if I didn't take over his temple, Rinso-in, I would have to remain at Zoun-in. That would be more calm, and I would be able to study more, but I determined to take it over, and there were two years of confusion and fighting.

Shunryu had mixed feelings about his own qualifications. On the one hand, there were many prominent older priests in the two hundred branch temples associated with Rinso-in. The abbot of Rinso-in wouldn't have any authority over them but would be required to serve a central function at occasional important ceremonies. At that time any slip in his demeanor would call into question his eligibility for the position. But he also felt, as So-on's number-one disciple, that he knew what So-on would want. He felt that Soko wasn't ready and would be used by others for their own ambitions, and that Ryoen and those whom he represented were definitely not good for Rinso-in. Shunryu did not want to see So-on's sixteen years of hard work go to waste. He was determined that Rinso-in not fall into the hands of greedy and ambitious priests. Keeping a low profile while strengthening his ties to important danka, especially Koga-san, the head of the temple board of directors, Shunryu patiently participated in ongoing discussions. He actually felt quite impatient and angry but kept these emotions in control.

Some saw him as the candidate who represented So-on's high standards. Others felt he was too young.

…

NEAR ZOUN-IN was a temple named Bairin-in. The abbot there was an old friend of So-on's and had been a close advisor to Shunryu, especially in practical matters.

…

Some of the danka at Rinso-in were not happy with the prospect of having a married priest. They had accepted Yoshi, the Daikoku-sama, as long as she was unofficial and kept a low profile. A wife would mean children, and there had never been a family at the temple. Many older people remembered the time when almost no priests had wives or families. One member suggested that Shunryu's family could live elsewhere. Another offered his house. Shunryu thought they were being extreme, especially as So-on had established a precedent by living with Yoshi there.

…

Shunryu, it had a zendo, having been a training temple with a number of monks in residence in the Meiji Era. He wanted to return Rinso-in to those days of glory, to develop it as a temple where both monks and laypeople could practice. He had helped So-on get the temple in shape and complete the refurbishing of the living quarters, but there was still a lot to do.

During the first three years of Shunryu's leadership, the congregation, buildings, and gardens of Rinso-in were put in good order. Almost all the families who had left returned. Shunryu gained a reputation as a friendly, gentle priest of good character and traditional values. So-on had been respected, but people were afraid to go to the temple when he was there. That changed when Shunryu took over. Rinso-in became a kind of community center where

various groups met to study Buddhism, practice the arts, discuss politics, solve neighborhood problems, and have small banquets and celebrations.

Chapter 6, Wartime

Kozo felt he could best contribute to Japan by helping to feed the population. There were almost unlimited possibilities in Manchuria for farming. He and his wife were heavily involved in the local Brown Rice Movement; they argued that eating white rice was a waste of nutrition and national resources. If everyone ate unhulled brown rice the nation could be better fed with much less. The Katos were influenced by Food to Win the War With, a book that advocated, among other things, eating more alkaline than acidic foods. Shunryu was familiar with such ideas from his master So-on.

Chapter 7, The Occupation

So-on had done the major restoration work on the Rinso-in zendo long ago, and now it was finally finished, appointed with new shoji, tatami that smelled of the fields, and a statue of Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. On June 3, 1947, there was a well-attended opening ceremony for this new zendo, a ceremony that affected the status of the temple. Now the Soto organization recognized Rinso-in as a temple with a self-supporting zendo. It was Shunryu's decision not to have a zendo supported by the Soto organization, since such support would include financial and other obligations on Rinso-in's part.

...

Shunryu had been a benevolent landlord, with a friendlier relationship with the farmers than untrusting So-on had had.

...

Shunryu scolded Yasuko a lot too, more than the others, because she was the oldest. The danka and neighbors would tell her what a quiet, soft, and kind person her father was. Yasuko wondered why he behaved so differently at home and suspected it was because of his strict temple training. Maybe he thought that was how a good father should be in order not to spoil the children; or maybe it was the dark side of So-on's heritage.

Chapter 8, Family and Death

Masaji Yamada, one of the senior danka of Rinso-in who lived just below the temple, had watched Shunryu carefully through the years. He was from the oldest and most conservative family in the village. Masaji didn't criticize Shunryu for going on the march.

"Everyone knows he is a pacifist," he said, "and especially pro-American at that, but he does not force his views on others. Like So-on, Shunryu-san is a priest as a priest should be. He recites the sutras well and isn't preachy."

Chapter 9, An Opening

In 1956 Gido asked offhandedly if Shunryu might like to go to San Francisco for a year or so to be an assistant to Hodo Tobase, the priest there. He didn't expect a senior priest like Shunryu to be interested in the assignment, but considering Shunryu's long-term study of English and interest in America, it was natural for Gido to bring it up. He couldn't find a priest who would go; there was no money or status in it. Shunryu said he wouldn't mind being an assistant and being poor, but that he couldn't consider going anywhere till he had finished the ambitious restoration work that So-on had started in 1918.

;;;

In the spring of 1958 the work on the main building--the founders', ancestors', and sutra halls--and the bell tower was finally completed. Ceremonies were held in March and May to commemorate the restoration, a job Shunryu had been involved with for forty years, a task he felt So-on had left for him to finish. So-on had restored only the family quarters and the zendo, the two wings off the buddha hall. "I could do the whole thing if I wanted to," So-on had told Shunryu, "but I must leave something for my disciples to do." Shunryu hadn't understood him at the time. Why not fix it all up now? he had wondered. Later he realized it was part of what So-on had transmitted to him.

When I made up my mind to go to America, I said to one of the members of my temple that if I could have gone ten years earlier, I might have been able to do many things. Maybe it was too late. I had forgotten almost all my English, and I regretted that I probably wouldn't be able to accomplish much. But then I thought, ten years before I didn't have so much understanding of Buddhism. So maybe it was a good thing for me to stay in Japan, finishing the work my master left for me.

IT WAS May 18, 1959, Shunryu's fifty-fifth birthday and his forty-second year of priesthood. With Hoitsu at his side Shunryu offered incense to his father, Sogaku, and his master, So-on, at the ohaka behind Zoun-in--the temple where he and So-on had lived so intensely, so intimately. How about me going to America? he had asked his teacher. So-on was adamant. No!

Twenty-nine years had passed. Now the answer was yes. How right So-on had been. How much Shunryu had learned. So-on had made him who he was, had guided him. Now he appreciated it. So-on had died, leaving those decaying beams still there, and Shunryu felt it was no accident. As he recited the Heart Sutra, his heart filled with gratitude. His appreciation for So-on had continually deepened over the decades. "When I offer incense to my father, I feel sad," he later said, "but when I offer incense to my master, tears stream down my cheeks."

Shunryu and Hoitsu visited the ashes site of the one Shunryu called So-on's wife, Yoshi Marushichi. They cleaned the area and made an offering. She'd been gone for six years now. While she was alive Shunryu had taken Hoitsu and the other children to visit her whenever they went to Zoun-in. She had lived to an old age and eventually was nearly blind. They always left her gifts of fruit and candy.

Part Two - America

Chapter 12, Sangha

In the downstairs auditorium several hundred older Japanese-Americans in suits and ties and Sunday best, not just temple members but guests from the whole Japanese-American community, sat waiting for him to enter. Scattered among them, tending to take seats in the back, were sixty or so mainly younger Americans in various styles of dress. Amidst the ring of high and low bells and the boom of a drum, struck by Richard Baker in the balcony, Suzuki proceeded upstairs to the zendo and kitchen altars to offer incense

and recite poems. Soon the chime of bells approached and a procession of guest priests, congregation officers, and children from both groups with flowers in their hands entered the auditorium. Following them Suzuki glided up the aisle as smoothly as a bride and stepped up to an ornate altar put together for the occasion. He offered a stick of incense and recited another poem. Next to him stood Bishop Yamada from L.A., who was officiating.

After I lift this one piece of incense, it is still there.

Although it is still there it is hard to lift.

Now I offer it to Buddha and burn it with no hand,

Repaying the benevolence of this temple's founder,

Successive ancestors and my master Gyokujun

So-on Daiosho [great priest]

Suzuki then ascended to the Mountain Seat, sitting in a lacquered chair on a platform beside the altar.

Chapter 14, Taking Root

He visited his family's ashes sites behind the temples at both Rinso-in and Zoun-in. He cleaned up the grave and offered incense to his master, Gyokujun So-on, to his father, Butsumon Sogaku, to his mother, Yone, to his second wife, Chie, to So-on's lover, Yoshi, and with great sadness to his daughter Omi, who had hung herself two years before. Suzuki was not proud of himself as a family man. On this trip he had brought to these departed loved ones his greatest offering and only atonement--Western disciples and the hope for his dharma seeds to be spread and to cross-pollinate the Buddha's way between the two cultures he lived and breathed.

Chapter 19, Final Season, Autumn

YASUKO SAW her father in a new light in America. Putting a positive spin on his misfortune, he told her he'd lived longer than he'd expected, that his master So-on had died at the age of fifty-five, he was now sixty-seven. The twelve extra years were his time in America. (Suzuki's chronological accuracy was sometimes off--So-on actually died when he was fifty-seven.) He was thin, soft, and open to her. She'd never felt closer to him and was sorry she'd seen so little of him since he left Japan. She could finally forgive him for the death of her mother and saw his accomplishments in America not only as atonement for but as partially motivated by her death.

*********************