Joko Dave Haselwood

He first studied with Suzuki Roshi in 1963 and told us many times how much he loved Suzuki Roshi. He mentioned, among other things, Suzuki Roshi’s ability for “spiritual Jujitsu” i.e. effortlessly diffusing a conflict situation and turning it into wisdom, opening the heart and mind of everyone involved on the spot. - Kaveh Moezzi

1-01-15

- It's 1am in Bali on the first day of 2015 and just had time to look at

email learning that Dave Haselwood, early Suzuki student and publisher of

Beats, died last night. Not unexpected. Dear friend gya te gya te. More

later. - DC - thanks Elizabeth Sawyer

1-01-15

- It's 1am in Bali on the first day of 2015 and just had time to look at

email learning that Dave Haselwood, early Suzuki student and publisher of

Beats, died last night. Not unexpected. Dear friend gya te gya te. More

later. - DC - thanks Elizabeth Sawyer

Empty Bowl Sangha was the group he started in Cotati. Used to meet in Cotati, then Penngrove, then Sebastopol

From Empty Bowl Sangha site (no more) page for Joko Dave - Joko Haselwood began practicing Zen with Shunryu Suzuki Roshi in 1963 but remained with him for only one and a half years. Later, he resumed practice with Jakusho Kwong Roshi at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center, and remained with him for fifteen years and was ordained as a Zen priest. He left Sonoma Mountain in 2000 and began studying at Stone Creek Zen Center with Jisho Warner Roshi. He received dharma transmission (permission to teach) from her and became Associate teacher at Stone Creek. He has led the Empty Bowl Sangha for many years. He emphasizes the practice of "just sitting" (Shikantaza) and the need to reconnect our body and mind in the practice of being present to life as it arises moment by moment.

Audio for Dave's lectures here on the Internet Archive. If you know where we can get his lectures to post on cuke other than there please let us know at dchad @ cuke.com.

Empty Bowl Sangha page on Stone Creek site as an affiliate zendo

Joko Dave Haselwood Interview on Sweeping Zen (also available below)

Dave Haselwood cuke interview - from 1999

Dave's anecdote in Zen Is Right Here

Auerhahn

Press - The upscale publishing house Dave started - Wikipedia (also

below)

Auerhahn

Press - The upscale publishing house Dave started - Wikipedia (also

below)

The Moon Eye and other poems by Dave - with an old photo

Dave Haselwood & The Auerhahn Press

A note on Dave's publishing with links here.

Much more about Dave and publishing on the Internet.

Dave, as I knew him, started studying with Shunryu Suzuki in 1963 and left after a year and a half. He said that a lot of grief started coming up during that time and he finally went to Shunryu Suzuki to mention he needed to leave, that he could not take the grief anymore and was surprised that Suzuki didn't oppose his desire to leave and told him “you try and try and fail and fail and then you go deeper”. Later he studied with Jakusho Bill Kwong for 15 years, was ordained as a priest, and then with Jisho Carey Warner for the past 14 years from whom he got re-ordained and eventually received Dharma transmission. He lived in Sonoma County where I was for sixteen years and I sat with his group every year or so and I'd drop by his funky little sheep farm in Cotati to chat with him. A son and a daughter lived with him there. There were two houses and a barn and over twenty sheep in the field. Continued seeing him after moving to San Rafael. Took Richard Baker by for a visit a couple of years ago. Saw him shortly before leaving for Asia a year ago.

Dave was a publisher in the fifties and sixties, the first to publish Michael McClure, whom he came to California with from the Midwest, and Philip Whalen. He'd been in close touch with McClure in recent years and said that McClure read and listened to his lectures. Dave was a soft-spoken, gentle, humble, insightful person. Farewell Dave. - DC, 1-01-15

From Philip Whalen's cuke interview

In 59 or 60 Dave Haselwood was working on my book, the Memoirs on an Interglacial Age, and he told me he'd been going over to Sokoji to sit with Suzuki Roshi and that he'd been doing dokusan with him but then I saw him later and he said he'd had one interview in which the old man told him, You don't ask enough questions. And this sort of crushed David and he kind of dropped out at that point. Not long after that he got involved with Alex North which cost him $300 a month that he didn't have and somehow he got it for the privilege of pruning vines or something at that neo-Gurgieffian heaven that North had set up in Sonoma or somewhere. Davey was up there for a long time and in recent years he got into Bill Kwong's garden and sesshin and he's going to have tokudo [ordination] up there.

[DC note: David Schneider confirms that Dave was working on this book of Philip's in 59 and 60, but Dave's period of sitting with Suzuki was 63-4.]

From Philip Whalen on Bill McNeill memorial- 6/17/02

I made a big magic memorial service for him at RCA Beach. Steve Allen and Mike Jamvold, Shunko, were my assistants. Issan, Joanne, Glenn [Todd], and Dave Haselwood were there.

[I was there too. - DC]

7-15-07 - Congratulations to Hakuun Joko, Dave Haselwood, on the final phase of transmission, the Bestowing of the Robe Ceremony, from Jisho Warner on Sunday July 15, 2007. Dave studied with Shunryu Suzuki in 1963-64 period at Sokoji in San Francisco. He was ordained as a priest by Jakusho Kwong in Oct. 1996 at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center then re-ordained by Jisho Warner in June 2003 at Stone Creek Zen Center in Sebastopol, CA. [later moved to Gratin] He received dharma transmission from Jisho Warner in June, 2007. His Cotati Sitting group is called Empty Bowl Sangha.

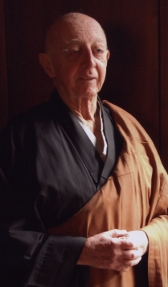

A recent photo taken not far from his home in

Cotati, CA by Eva Moezzi.

The little park in the background was designed by Joko who was also a

landscape architect and the fountain was designed by someone he called his

dear friend.

A note about Joko Dave from Kaveh.Moezzi

I woke up early this morning and this verse came about Joko who was from Kansas and had told me Kansas was his favorite place on earth and also that he was sad he would not see it again. I really hope he has seen it again now.

Hope it is possible to publish below as well. I want to also send it to his Polish friends who loved him (and he them). He had a love affair with Poland, from the time he went there with Kwong Roshi about 20 years ago.

The white cloud intermingles

With the vast bright sky

Dissolving into clear light

At night the moon is reflected

In a field in Kansas

All ancestors welcoming home

The tired old man

What stays is the wonder

I met Joko Dave Haselwood in the mid 1990’s in Sonoma Mountain Zen Center. He was a senior student of Kwong Roshi at the time who later was ordained as “Joko”, clear or pure light, by him. Joko mentioned to me that the name was suggested to Kwong Roshi by Hoitsu Suzuki Roshi.

Joko led the study group at SMZC. He was a genuine scholar with a vast knowledge and deep love of Zen. I asked him once what his favorite Dharma books were and he mentioned Uchiyama Roshi’s Refining Your Life and Opening the Hand of Thought first along with Dogen. He made Uchiyama Roshi’s books the topic of his course in SMZC along with a host of other books, among them Joko Beck’s “Nothing Special”. He really liked Joko Beck’s clear non-mystical approach even though he also loved the zen koan’s and poems by the old masters, most notably Dogen and also Joshu who he mentioned was his favorite Zen Master of all. He admired Joshu’s commitment to practice as he studied till he was 80 years old before starting to teach and then taught till he was 120 apparently. He first studied with Suzuki Roshi in 1963 and told us many times how much he loved Suzuki Roshi. He mentioned, among other things, Suzuki Roshi’s ability for “spiritual Jujitsu” i.e. effortlessly diffusing a conflict situation and turning it into wisdom, opening the heart and mind of everyone involved on the spot.

Joko had a deep love of Poland and Polish people. He went to Poland with Kwong Roshi about 20 years ago and fell in love with the people and the place. He gave multiple Dharma talks, private Dharma interviews and traveled extensively in Poland staying with Sangha friends. My wife who is Polish recalls that his talks were very heart warming, jovial and full of earthy humor. Wherever he went, he was very warm with the people and also learned a decent amount of Polish due to his curiosity and intellect. He spoke of this love for Poland and the Polish to the end of his life.

Joko also had a vast knowledge and love for nature. He loved birds, trees, flowers, plants, animals, enjoyed hiking by the ocean, in forests and every year loved to go to the mountains in Arizona with his old Dharma friend, Charles (I don’t know his last name).

DC note: He also went on regular nature walks with Michael McClure, Joanne Kyger, and Sterling Bunnell.

He also loved poetry, was a publisher of books and the Beat poets in the 60’s. He was like a walking encyclopedia and the river of his life had wide and deep banks, running for a long way.

He left Sonoma Mountain in 2000 and started studying with Jisho Warner from whom he received dharma transmission in 2007. He had a sitting group for years in various places in Cotati and just a couple of months ago the sitting group moved to Sebastopol. Many of his Dharma talks are on the web on the Empty Bowl Sangha web site.

Regards,

Kaveh

Joko Dave Haselwood Sweeping Zen Interview

Posted by: Sweeping Zen December 25, 2009

Completed on June 25, 2009

Joko Dave Haselwood is a Soto Zen priest and guiding teacher of Empty Bowl Sangha in Cotati, California. A Dharma heir of Jisho Warner, Haselwood is also an Associate Teacher at Warner’s Stone Creek Zen Center. Additionally, Dave counts among his teachers Shunryu Suzuki, Philip Whalen and Jakusho Kwong. He is also a member of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association of North America. Dave was a joy to interview and I wish to thank him for participating.

Website: http://emptybowlsangha.org/

Transcript

SZ: What initially drew you to Zen practice?

JDH: At age seventeen I moved from a town of three hundred people in the Flint Hills of Kansas to the University of Kansas in Wichita (this was in 1948). Going from being a dreamy, poetry reading farm boy, to being the pet of a tiny bohemian clique of teachers and students occurred almost overnight. A jazz musician from Kansas City handed me a book with a cover that had the word Zen in large letters on it—I don’t know what that book was but it must have been by D. T. Suzuki. I remember asking, “What the hell is Zen?” The musician proceeded to tell me, although I can’t remember anything he said today. It must have impressed upon me deeply, however. The word lay in me like a bomb waiting to go off, far, far, in the future. Among my friends at that rural Bohemia was a very young poet, Michael McClure, who later became famous as one of the original Beat Poets. It was he who eventually introduced me to Philip , whom I consider my first Zen teacher.

We are now talking about the late Fifties. I had been stationed in Germany in the army during the mid Fifties where I was a peripatetic reporter for a Divisional newspaper, again dreamily reading poetry and the Upanishads. I occasionally corresponded with the Wichita poets and artists, many of whom had moved to San Francisco and were part of the poetry movement which was to include the so-called Buddhist branch of Beat Poetry: Philip Whalen, Lew Welch, Gary Snyder, Joanne Kyger and Jack Kerouac. That is the scene I walked into when I moved to San Francisco in 1957. I opened a small publishing and printing firm that I called The Auerhahn Press. My third book was Whalen’s Memoirs of an Interglacial Age. So, you might say, poetry brought me

SZ: Tell me if you will about your three primary teachers – Shunryu Suzuki, Jakusho Kwong and Jisho .

JDH: When I see those names lined up together, and especially if I add to the list one Philip Whalen, I ask myself, “What in the world do those people have in common?” And I tell myself, “Go chant once again the Sandokai!” I stumbled into Sokoji on Bush Street one morning in 1963. When he saw how helpless (or, perhaps hopeless) I was, Suzuki Roshi showed me how to sit, gave me a brief upper back massage with the remark that I had the stiffest back he had ever seen, and left me to my own resources for the next year and a half. He was an amazing and kindly teacher with an acid tongue, and easily the most intriguing person I have ever met. I adored him, but he scarcely ever gave me the time of day. I’d never even had dokusan with him until the day I left Sokoji. Being in his vicinity was a constant learning experience and the Sangha was quite small at that time, maybe fifteen or so steady sitters. The feeling was very intimate but not at all cozy. Members I knew fairly well included Trudy and Mike Dixon, Richard Baker and his wife Ginny, Philip Wilson and, to a lesser degree, Bill Kwong and his wife Laura. One thing Suzuki Roshi had in common with his son Hoitsu Roshi—who I got to know from his frequent presence at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center and who gave me the name Joko—was that they both moved and used their bodies with grace and to constantly teach. Words were of secondary importance. Suzuki Roshi’s admonition to me, when I told him that I was leaving because I was in too much mental turmoil and physical pain to continue, was simply this: “You try and try and you fail. Then you go deeper.”

I decided that I needed to do some serious psychoanalysis and Gurdjieffian karma yoga because I felt alienated from my body and very poorly grounded. So I joined a Gurdjieff group, got married and began raising children, moved into rural Sonoma County, and worked with a terrific psychiatrist named Michael Agron—whom I also consider to be one of my key teachers.

One day I got a call from the poet Joanne Kyger with the message that she was staying for a few days in a cabin at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center and that I should come up and see my old friend Jakusho Kwong. I went up the mountain and almost didn’t come down—I felt that I had returned home when I walked into the beautiful barn-zendo there. On the following Saturday, which was Buddha’s birthday, while chanting the Heart Sutra, it was as if a gong sounded inside my chest: Yes! So, for the next fifteen years, I threw myself once again into the practice, never missed a sesshin, went up and down the mountain every day during angos, was Shuso once before ordination and once after, received the precepts (and received at that time the name Hakuun – White Cloud), gave endless study groups, and took care of the beautiful stupas every week without fail. My wife totally backed me in my dedication and never once complained. I was working full time as a landscape architect, but the Zen practice seemed to give me unending energy. Kwong Roshi is not a word man; he teaches Zen as an artist. Oryoki meals at Sonoma Mountain are like choreographed ballets—everything is simple and elegant down to the slightest detail. The training is excellent, the programs beautifully organized and executed, and Kwong Roshi and his wife (who is the Tanto) Shinko move through all this with grace but also iron will.

Unfortunately, Kwong Roshi and I never established the kind of relationship that is essential between a student and his teacher. And, when I realized that I was committed to a life of Zen practice, I wondered where all this training was leading since there seemed to be an increasing distance between Roshi and me. When I confronted him with this he simply said that I was not what he wanted in the way of a dharma successor. An endless life of teaching study groups and being the doddering old man with the rake down at the stupas, without being a teacher, seemed fruitless to me.

Just at that time, Jisho Warner and Shohaku Okumura came for lunch to the Mountain and Jisho and I immediately hit it off. We walked down to the stupas together and the communication between us was like a cool wind: open, unconstrained and illuminating. Something in me took note and as my relationship with Kwong Roshi grew colder; I decided to go to Jisho, ask her to be my teacher. The whole incident was traumatic, but Jisho arranged to call on Kwong Roshi and get his permission to re-ordain me—everything went smoothly. The years with Jisho (I still give talks at Stone Creek and attend Sunday mornings when my health allows it) have been invaluable and her training thorough, although she never demanded that I train in Japan for a period. She herself is that rarity, a teacher who was given transmission by two teachers: Tozen Akiyama and Ayoami Roshi, the Abbess of the Soto female monastery in Japan. She also trained for years with Katagiri Roshi, so her knowledge and understanding of Zen practice and training is very broad and deep. For

SZ: Several old-time masters are said to have settled the Great Matter without any formal study at all. Should zazen practice be coupled with sutra study and the reading of Dharma books?

JDH: Anything and everything is possible. I don’t ask my students to read sutras but I know that I had damn well better read them myself! There is also the factor of Western ignorance of the most fundamental teachings of the Buddha. Bright students should be tackling Dogen as early on as possible, less able students need more personal direction and so forth. Ideally, each student gets what he or she needs. The doctrinaire approach is a machine for creating suffering. But, as a general rule, most students profit more from hearing a teacher talk about a Dogen essay than they do reading in on their own.

SZ: One often hears that anyone can practice Zen, but is it really for everybody?

JDH: Zen is for everyone but Zen training certainly is not! I deal with all kinds of people daily, most of who have never heard of Zen before. And yet to the extent that I live Zen, everyone is able to benefit from Zen. That is what it means to be on the bodhisattva path.

SZ: You lead a sitting group in Cotati, California that you call Empty Bowl Sangha. Tell us a bit about the group, it you will.

JDH: The Sangha is small, about the same size as Suzuki Roshi’s in 1963. I try to keep it small because I like lots of individual instruction and interaction with students. I am an old man, so I tend to attract older people who have been with other teachers and so don’t require coddling. But I also have students who are younger and therefore still wandering around. One of these calls me every two weeks and we do phone dokusan a la Joko Beck. The only chanting we do is The Four Vows and occasionally the Heart Sutra and Enmei Juku Kannon Gyo. As an heir of Dogen’s teaching, I strongly emphasize Shikantaza and as much of it as I can wring out of the students.

SZ: What books would you recommend to someone interested in Zen?

JDH: Suzuki Roshi’s Zen Mind, Beginners Mind; Uchiyama Roshi’s Refining Your Life and Opening the Hand of Thought; Walpola Rahula’s What the Buddha Taught; and, for certain temperaments, Chogyam Trungpa’s Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism and John Tarrant’s Bring Me the Rhinoceros.

Share !

Tagged with: JAKUSHO KWONG JISHO WARNER JOKO DAVE HASELWOOD PHILIP WHALEN

About Sweeping Zen

Established in 2009 as a grassroots initiative, Sweeping Zen is a digital archive of information on Zen Buddhism. Featuring in-depth interviews, an extensive database of biographies, news, articles, podcasts, teacher blogs, events, directories and more, this site is dedicated to offering the public a range of views in the sphere of Zen Buddhist thought. We are also endeavoring to continue creating lineage charts for all Western Zen lines, doing our own small part in advancing historical documentation on this fabulous import of an ancient tradition. Come on in with a tea or coffee. You're always bound to find something new.

Pasted from <http://sweepingzen.com/joko-dave-haselwood-interview/>

Wikipedia on Auerhahn Press (copied 3-17)

Founded by printer-poet Dave Haselwood in 1958, the Auerhahn Press published many key poets of the San Francisco Renaissance.

Stated in advertisements appearing in Evergreen Review, Poetry, City Lights Journal and Big Table magazines, the press’s goal was “to re-marry good printing and writing,” and to this end the Auerhahn published 28 letterpress-printed titles between 1958 and 1964. Most were chapbooks handset by Haselwood, later with Andrew Hoyem, in a creative and subtle variety of fonts. Its first title was The Hotel Wentley Poems by John Wieners.

The press was based in San Francisco and published the first books of many emerging and soon-to-be influential poets, including Wieners and Lew Welch. Its catalogue, uniformly out of print, includes works by Jack Spicer; Diane DiPrima; Philip Lamantia; Michael McClure; Philip Whalen; David Meltzer; William Everson (Brother Antoninus); Charles Olson; and the first edition of Exterminator, an early collaboration in cut-ups by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin. These among others were the “insurgent American writers” that the press detected in its search for the “bold, free and courageous in modern writing.”

Thanks to the printer’s touch as much as to the collaborative energies of artists like Bruce Conner, Ray Johnson, Robert LaVigne, Robert Ronnie Branaman and Wallace Berman, the Auerhahn’s books—and its ephemera—seem to float in the

“The first & final consideration in printing poetry is the poetry itself,” Haselwood wrote in 1960. “If the poems are great they create their own space; the publisher is just a midwife during the final operation & if he has to do a lot of dirty work that’s the way it should be. Contrary to what a lot of people including publishers think, publishing is not a gentleman’s profession, it is the profession of a crook or a madman.”

As the press grew influential, if not solvent, artistic conflict followed, most notably with DiPrima, Robert Duncan (who canceled his book in mid-production), early collaborator Jonathan Williams, and Spicer, who in an occasional poem dated October 1, 1962, wrote: “This is an ode to John Wieners and the Auerhahn Press / Who have driven me away from poetry like a fast car.”

In 1964, Haselwood turned production and last rites of the Auerhahn Press over to his partner Andrew Hoyem and started Dave Haselwood Books.

As an Amazon Associate Cuke Archives earns from qualifying purchases.