Edward "Ned" Johnson

Ned Johnson, as he was called, continued his father's support of the

SFZC most generously

through the years. I met him two times. Once in 1973 when I was

Richard Baker's jisha, and the second time in 1999 when he expressed an interest

in supporting the digitization and transcription of Shunryu Suzuki's audio

archive. We should all be most grateful to him and his family and his family

fund for their substantial contributions that have helped significantly to

establish Shunryu Suzuki's way in the West. - DC  Edward

C. Johnson III, 91, Dies; Made Fidelity an Investment Giant Edward

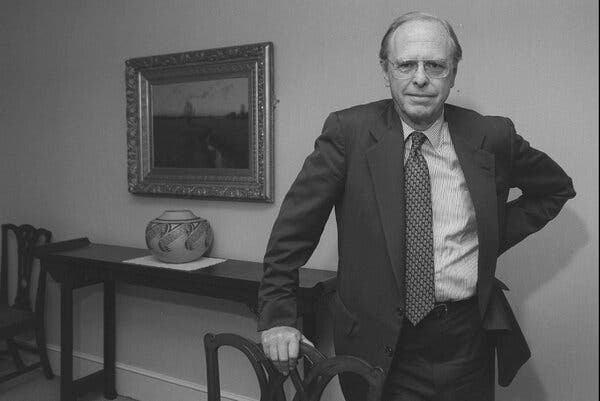

C. Johnson III, 91, Dies; Made Fidelity an Investment GiantFrom the NY Times March 24, 2022 Mr. Johnson’s exceptionally long tenure — he presided over Fidelity into his 80s — coincided with a huge expansion of his industry. Edward C. Johnson III, the chairman of Fidelity Investments, in 2004. He joined the firm as a junior stock analyst in 1957 and remained in charge into the 2010s. Edward C. Johnson III, the chairman of Fidelity Investments, in 2004. He joined the firm as a junior stock analyst in 1957 and remained in charge into the 2010s.Credit...Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images By Robert D. Hershey Jr. Alex Traub contributed reporting. March 24, 2022 Edward C. Johnson III, a publicity-shy Bostonian who transformed a small company created to manage the department-store wealth of his Mayflower-pedigreed ancestors into one of the world’s biggest investment companies and the nation’s largest administrator of workplace retirement plans, died on Wednesday at his home in Wellington, Fla. He was 91. The death was announced on LinkedIn by his daughter Abigail, the current chief executive of the firm, Fidelity Investments. Mr. Johnson, widely known as Ned, led FMR, Fidelity’s parent company, and drove it to prominence in the 1960s with heavily promoted, aggressively managed “go-go’’ stock funds. In 1974, the company helped popularize the fledgling money-market business by allowing customers to write checks against its money fund. “They were the unquestioned industry leader,” John C. Bogle, founder of the archrival Vanguard Group, which favored a more conservative market approach, less reliant on star portfolio managers, and eventually overtook Fidelity in assets under management, said several years ago in an interview for this obituary. (Mr. Bogle died in 2019.) Mr. Johnson’s exceptionally long tenure — he joined the family firm as a junior stock analyst in 1957 and presided over Fidelity into the 2010s, when he was in his 80s — coincided with a huge expansion of industry products as well as assets, and he eagerly embraced technological advances to provide services that later became commonplace. He first offered retail customers the ability to conduct transactions by toll-free telephone; he pioneered walk-in investor centers; and he revived, and then popularized, funds focused on specific industry sectors, like health care. At his death, Fidelity had more than 500 mutual funds and $11.8 trillion under administration. The company, about half owned by the Johnson family and half by its other employees, had revenue of $24 billion and operating income of $8.1 billion. “He was a true visionary,” said John M. Boyd, a financial services executive and a former Fidelity employee. Mr. Johnson in his dining room at the Fidelity offices in Boston in 1994. Mr. Johnson in his dining room at the Fidelity offices in Boston in 1994. Credit...John Bohn/The Boston Globe Besides its huge stable of mutual funds — which included the Magellan Fund, managed by Mr. Johnson before Peter Lynch piloted it to superstardom — Fidelity’s businesses came to include a huge division administering 401(k) plans and maintaining other records for companies. It also provided discount and institutional securities brokerage; was active in real estate; and owned a group of weekly community newspapers and even a limousine and bus service, which was said to have been created when Mr. Johnson was once unable to hail a taxi. The Johnson family, which has Boston roots dating to 1635 and made its initial fortune with the C.F. Hovey & Company department store, has long been one of New England’s leading philanthropists, often anonymously, particularly in the visual arts. Mr. Johnson’s personal art collection is valued in the scores of millions. Edward Crosby Johnson III was born on June 29, 1930, in Boston, and grew up in Milton, a suburb. His mother, Elsie, was a homemaker. Ned was an indifferent student, but after attending various private schools — he once informed a teacher who had corrected his spelling that he would always have an aide to do proofreading — he managed to enter Harvard at 20. He graduated in 1954. After graduation and a stint with the U.S. Army in Germany, Mr. Johnson took a low-level job at State Street Bank before joining the small mutual fund in which his father, Edward II, had invested. He took control of it in 1946. Mr. Johnson quickly showed promise as a stock analyst and portfolio manager under the tutelage of Gerald Tsai Jr., a celebrated gunslinger of a portfolio manager. As the story goes, Mr. Tsai was told by Mr. Johnson’s father one Saturday in 1964 that Mr. Tsai would take over the company, but the senior Mr. Johnson had a change of heart over the weekend and decided that his son should run Fidelity instead. Mr. Tsai wound up selling his stake in Fidelity and moved to New York, where he created the Manhattan Fund and became a billionaire corporate financier. He died in 2008. For decades, Fidelity was the subject of intense speculation about whom Mr. Johnson would designate as his successor. After holding various senior positions at the company and becoming for a time its largest shareholder, his daughter Abigail was named chief executive in 2014. At his death, Mr. Johnson’s title was chairman emeritus. Last year, Forbes magazine ranked Abigail Johnson and her father as the 27th and 60th richest people in the world, with assets totaling $36.7 billion. His only son, Edward IV, is president of Pembroke, a real estate firm affiliated with Fidelity, and his other daughter, Elizabeth, is not involved in the family business. In addition to his children, Mr. Johnson is survived by his wife, Elizabeth (Hodges) Johnson, whom he married in 1960, and seven grandchildren. In 2007, in a rare interview, Mr. Johnson ruminated to Institutional Investor magazine about managing private companies. He declared that while outsiders may be given important roles, family members need to be prominent to provide stability “and an ongoing philosophy or culture of doing things a certain way.” A major element of Mr. Johnson’s managerial style was his adoption of kaizen, a Japanese strategy involving constant incremental improvement that he learned about from a book he had found in the gift shop of a Tokyo hotel. He hired the author to lecture Fidelity executives, made a video about kaizen for new employees and wrote the foreword to another kaizen book, which included Fidelity as a case study. Observers have often suggested that Mr. Johnson’s devotion to kaizen might explain the frequent personnel shifts at Fidelity, including Mr. Johnson’s removal of his daughter Abigail as head of the mutual fund division, which was suffering from mediocre performance, in 2005. A chronic experimenter, Mr. Johnson fomented intense competition among fund managers and other staff, sometimes giving two employees the same assignment to see which would produce the better solution. He fiercely defended the independence and privacy afforded by Fidelity’s family ownership, and he fought efforts by the Securities and Exchange Commission to require the separation of fund governance from that of management-company sponsors. Mr. Johnson in 2008. He fiercely defended the independence and privacy afforded by Fidelity’s family ownership. Mr. Johnson in 2008. He fiercely defended the independence and privacy afforded by Fidelity’s family ownership.Credit...REUTERS/Brian Snyder He said he was proud of his dual role as an owner of the management company and chairman of the funds’ board of trustees, insisting that shareholders’ best protection is not “laws or a chairman’s so-called independence” but the “moral fiber” of the leadership. Mr. Johnson also unsuccessfully opposed an S.E.C. initiative to force fund companies to disclose how they vote portfolio shares. Considering his means, Mr. Johnson’s lifestyle was modest. His three-story brick townhouse in the Beacon Hill neighborhood cost $117,500 in 1970 (the equivalent of about $850,000 today) but boasts a garden, shared with neighbors and that, according to Boston magazine, was once the site of grand literary salons frequented by such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Dickens and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. A frugal, tough negotiator, and obsessive about detail, Mr. Johnson never built an impressive headquarters. He was content to run his far-flung empire from an unadorned nine-story structure marked “Fidelity Building’’ by small bronze plaques. Although Fidelity was often criticized for lacking transparency and accountability to outsiders, which some say hurt its competitiveness as it saw its share of the fund market shrink in recent years, Mr. Johnson was adamant about maintaining the company’s freedom of action and privacy. “Ned Johnson is an old-style proper Boston Yankee who thinks you’re boasting and acting unseemly if you get your name in the paper,” said the financial journalist Joe Nocera, who writes regularly for The Times’s DealBook newsletter. “When his advisers once told him that Fidelity would have to talk to the press, his response was ‘Fine, as long as it’s not me.’” He did, however, partly lift the veil of reticence and mystique when, to commemorate the company’s 50th anniversary in 1996, he ordered the staff to produce a history that inevitably became the story of the Johnson family. The limited-edition two-volume work was titled “There Will Be Dancing,” a reference to the instruction Mr. Johnson’s father gave for planning his retirement party. In an interview a decade earlier, an intrepid reporter asked Mr. Johnson when Fidelity might offer its stock to the public. His terse reply: “When I’m dead and buried.”  Thanks John Steiner for alerting us to this article and Ned Johnson's passing. |