Jack Novcich

Memories of Old Jack

by

Laura Burges

Jack is mentioned and quoted in

A Brief History of Tassajara.

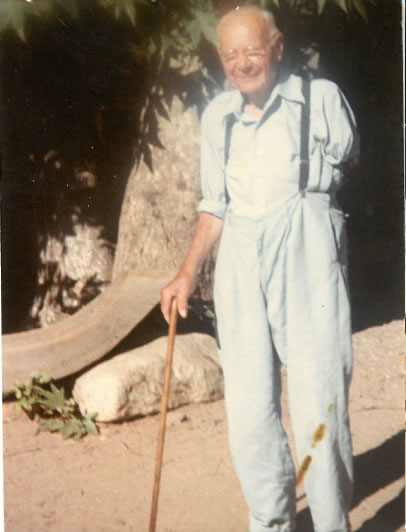

and thanks, Laura, for the photo of Jack - standing on the road to the baths at Tassajara. - dc

A small but growing oak tree grows near the railroad bell at Tassajara. Some years ago, Thich Nhat Hanh and a group of children planted this tree during a ceremony for World Peace. Another tree once grew near this spot. It was a huge sheltering oak, who knows how old. The people who came to Tassajara in the old days called it the Gossip Oak because folks would stand in its shade, greet their friends, and talk of this and that.

Jack Novcich, a longtime Tassajara guest, told me about the Gossip Oak. He first visited Tassajara in 1914 and returned every summer until he was nearing 100 and couldn’t get around much any more. He died in 1991 at the age of 103.

Jack was born near Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, in 1888--the year Van Gogh did his best work--and came to this country in 1906. He bought a shovel for 75 cents and helped build the New York Central Railway. The only English he knew at the time was, “I have shovel, I can work.” He made his way out West and worked for a time at Tadich Grill on California Street here in The City. Later, he moved to Watsonville.

On January 6, 1914, Jack was working on a road crew in the Santa Cruz Mountains. His nickname was “Dynamite Jack” and he helped build roads through the mountains between the Central Valley and the Coast. One day, he picked up a metal pole and was setting it in place when it touched a high-tension wire and sent a scorching electric shock through his body. When he woke up in the hospital, his left arm and his right leg had been amputated. Jack was engaged to be married at the time and, though his fiancé wanted to honor their commitment, he decided it would be best not to hold her to it, though they remained friends througout their lives. That same year, he opened a cigar store in Watsonville so that he could support himself and, that summer, came to Tassajara for the first time, believing that the water would help him heal. He ran his cigar store seven days a week, except for his annual two-week vacation to Tassajara, for 65 years.

Jack often accompanied The Watsonville Domino Club to Tassajara in early years. before Zen Center’s time. This loyal group of friends stayed down in the Pine Rooms and enjoyed copious amounts of beer, square dancing and lamb roasted on a spit over a fire. “Now all you got is brown rice and tea,” Jack teased.

When people asked Jack the secret of longevity, he’d lean forward, and wink. “Raise hell,” he’d say. But at other times he attributed his long life and good health to drinking the mineral water that ran out of the rocks near the old steam room at the original bathhouse. “Early days, people came here for their health, any kind of sickness, they came here to drink that water over there. In the morning, first thing when you get up. Whole families used to come here. They’d come from the Jeffrey Hotel in Salinas in a bus. In those days you could make about $2 a day and it cost $18 a week to stay here.” Jack could hold forth for hours, talking about his life in Yugoslavia or cataloging the many different owners and eras he lived through during the years he visited Tassajara.

I met Jack in 1975 when I first came to Tassajara as a guest student. For about ten years, I came back to cook during the summer guest season and I’d spend as much time with Jack as I could, listening to his stories and helping him--but only when he wanted help. One time in the dining room I watched him put his red napkin under the stump of his left arm and fit the napkin ring over it. I tried to help but he gently dissuaded me, “I have to do everything I can do or pretty soon I won’t be able to do anything for myself.”

Another time, when he was feeling his aches and pains, he clenched his fist and smiled sadly at me. “Old age. It gets hold of you… and it squeezes and squeezes.”

I had told Jack that I had hitchhiked up the coast of Yugoslavia during my travels. When my folks came to visit me at Tassajara, I invited Jack to join us for dinner in the dining room and admonished him not to mention my hitchhiking adventures. During the meal, he kept jerking his thumb up and down and grinning playfully at me and finally said, “I can’t help it—I’m gonn tell ‘em!” And he did.

Jack told me that in the village where he grew up, everyone knew everyone else. If someone stole something and they were found out, everyone in the village would stand silently outside their houses and the offender would have to carry the stolen goods past every house and return them to the owner. “Never happened twice,” he claimed.

Jack had an artificial leg, though you wouldn’t have known it as he always looked dapper in light blue slacks, wingtips, and a blue shirt with a vest. A gold watch chain was draped from one pocket to another, a watch he got from a customer who gave it to him as collateral for a loan in 1920 and never came back. The cherry wood cane he used was the same one he first bought after his injury and the sturdy leather suitcase he brought to Tassajara every summer was the one that came with him from Yugoslavia.

Jack’s neice Novenka came over from Yugoslavia to Watsonville to help him out. He was rightously indignant when she got ahold of his battered straw hat and his treasured suitcase and got rid of them, replacing them with bright and shiny newer versions. When I met Novenka later, I understood that she loved her uncle deeply and didn’t want him to appear “foolish.” Later, Novenka married and she and her husband helped keep the cigar store going, with its gleaming dark wooden bar and shelves and tables, a bit of Watsonville history.

To me, Jack was like the ferryman in Siddhartha. He planted himself in the life in which he found himself. He was loyal to his friends and to the fine and simple things he owned. He did the best he could with what he had and he made a good life for himself. He found pleasure and dignity in everyday life. One time when I was visiting him at the cigar store he nodded at the old men there, sitting on stools. “These old fellas?” he said. “They used to steal gum from me when they were little boys.”

It was Jack’s theory that the Gossip Oak died because the “Zens” mixed concrete at its base when building the kitchen and thatj lime killed the roots of the tree. But he understood that we were young and didn’t really have a clue.

I never really knew my own grandfathers. Jack became my adopted grandfather and I named my daughter Nova after him. Jack had one foot in the 1800’s and the other at the end of the 20th century. He lived from the time of the horse and buggy to the time of computers and jet travel. When he passed, a world passed with him. Yet those of us who practiced at Tassajara during his time there carry the memory of old Jack with us.

“Raise hell.” Yes, indeed.