Interview with Loly Rosset

7-20-12 - Loly Rosset passed away this morning.

Received from her son:

Dearest Family and Friends of my mom, Hannelore "Loly" Rosset:

Loly passed away peacefully this morning here in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico, at 6:29 am. She was born on August 29, 1923, and left this world today, July 20, 2012, after almost 89 years. She had suffered a massive stroke several days ago, and was unconscious for the past several days. Thankfully she had enough remaining consciousness last Sunday night to recognize me upon my rushed return from Indonesia to say farewell. In accordance with her wishes, we brought her home to the small house we built for her on Tuesday, were she rested peacefully in her own bed, surrounded by family and friends, until passing away. I thank enormously my beloved compañera María Elena for her affection and accompaniment in these difficult days.

- Peter Rosset.

I first met Loly Rosset in the sixties at Tassajara, maybe the first time was when she came with the group of visiting teachers in 1968 - Yasutani, Soen, Shimano, Maezumi, Aitken. She's sat with them all. Later she came to spend time at Tassajara, Page Street, and Green Gulch. In later years I'd visit with her at the Redwoods Retirement Community in Mill Valley. She had a fascinating history in her native Germany, in the New York literary scene with her husband publisher Barney Rosset, and in emerging world of Zen in America. She was a smart, alert, and thoughtful woman. Farewell Loly and congratulations on a courageous life. - dc

7-17-12 - Loly (Hannelore) Rosset has had a severe stroke

Dear Friends of Hannelore (Loly)

My mother Loly had a severe stroke and is in the hospital

here in Mexico and is semi-unconscious. We don't know if she will make it.

Please help me spread the word to family and friends.

Thank you and lots of love,

Peter Rosset

Loly Rosset on Suzuki Roshi

Interviewed by DC at his home in San Rafael

6\15\95

During the first hour and a half of the tape, Loly recounted her life in Germany where she was born in 1923 till she came to America in 1951. Notes from that interview are below after her Zen memories including those of Shunryu Suzuki, Soen Nakagawa, Eido Shimano,

See Loly Rosset's memories of Europe

One aspect of Loly's life not touched on in this interview is that she was married to Barney Rosset who founded Grove Press and Evergreen Review.

RIP Barney Rosset, Grove Press and Evergreen Review - Richard Baker's earliest ventures into publishing. Hannelore (Loly)Rosset, his 2nd wife, is whom he got to translate The Blue Cliff Record from the German case by case, until Cleary's book came out.

Loly Rosset's Zen memories

When Suzuki Roshi came to New York in the last years of his life he usually stayed with me in my apartment which was wonderful. They offered to let him stay at the zendo but according to Yvonne after he'd stayed with me once he always wanted to stay with me and I was delighted. I was involved with the Zen Studies Society at the time. That's where I started in fifty, sixty something. First I studied tea ceremony for about eight years then from that I heard of the Zen Studies Society where I did sesshin with Yasutani Roshi and Tai-san, which Eido [Shimano Roshi] was called then, in various places that we rented. Shortly after I started there I became Tai-sans's assistant and I did whatever had to be done including cooking, laundry and making tea, and helping his wife and he always asked my advice. We were like three friends working together and he'd ask things like should we make decisions democratically and I said no you must decide. I was too much that way at that time. When we moved to the big fancy place in uptown Manhattan on the East Side, I had a bigger office. Soen Roshi came also and sometimes we had sesshins with all of them.

I remember when all the roshis where in Tassajara, Yasutani, Eido, Soen, Suzuki and I had just come in from Los Angeles and we went up to the top of the mountain for the sunset. I remember you saying, "Hey guys, let's go over there to get the roshi vibes."

That was the second year Tassajara was open and I'd started at Zen Studies two or three years before that. When I heard about this new place, Tassajara, and Suzuki Roshi and said I wanted to go there, Tai-san put up an anonymous sign quoting some Zen teaching that said the teaching is everywhere and you don't have to go all over to study, something like that but I wanted to go to San Francisco and Tassajara, it all sounded very appealing to me. He didn't like that. I could read his thoughts and he could read mine and whenever it came to a test it was always true and we always laughed but we never talked about it.

Then later on I had this kind of strange rapport with Soen Roshi and it was a little bit like that with Suzuki Roshi when we were alone. So I saw the sign but I made it clear that I wanted to go so Eido Roshi made it clear that he had to go also to receive Yasutani Roshi from Hawaii where he had given a sesshin so he said why don't we go together to Los Angeles which I thought was nice and then it turned out when we got there, he took me to a friends who didn't like the idea of putting us both up and they thought that was strange but I didn't know about that other side of Eido-shi's at that time. I was totally innocent about his thing with women though at Tassajara a few days later something happened that made it pretty clear - someone came with a flashlight. So I went to a motel in LA. And we met Yasutani and Aiken and Soen and we all went to Tassajara and it was all because I insisted on going there - it sort of snowballed. It wasn't planned or anything. It must have been '68, in the summer.

I remember meeting Suzuki in his hut with three or four other people - you know, how people would greet him when they first came. He looked at me and said, "You have a big nose." It just came out of him. I was very impressed by him because he was so simple, unneurotic and a little shy and so unlike most people. I immediately felt good with him - I couldn't help - like most people. There was just something about him, his ordinariness and a mixture of great clarity and intelligence and a little bit of Dennis-the-Menace humor in one of his eyes, the way the one eyebrow raised.

When we were at Tassajara there was an earthquake while Soen Roshi was talking and the kerosene lamps shook. Soen Roshi was a very different apple. He was more like a shaman, kind of a crazy artist. All of the roshi I knew were so different one from the other. Soen Roshi immediately made a thing out of the earthquake like it had some sort of significance. And I remember on that visit in the hot dry summer that it suddenly rained out of a blue sky and Soen was tuned into that kind of thing and used it as a teaching device.

I remember you dropping all the bowls - you came through joking with the plates so high and a mischievous expression on your face and someone came through teasing you and you dropped the whole thing - it was hilarious because you were trying to pull it off and you didn't. You were so naughty. You were wonderful - without you, the place would have been very different.

We went up to the top of the mountain to spread Nyogen Senzaki's ashes and I rode in a pickup truck.

DC: I remember being in the back of a truck with Eido and he said that there are only two types of people: those who know and those who don't. I thought that was terribly simplistic.

LR: Well, his background was very simple, he was just a country monk. I was quite aware of him. You can't expect too much. This is true of the other teachers too. We lifted them up into some kind of stratosphere. They thought it was all some kind of big news to us and some of these things weren't to me but maybe it was news to some of us. Some know and some don't know, hmm, each of us has a different version, I guess you could make a statement like that and attach a lot of meaning to it depending on what it is you're aiming at.

I remember you offered to make a table for Eido - you were very enthusiastic about giving him a present. I was very touched by that.

DC: I needed something to do in my spare time and I liked to make tables.

LR: At one of my visits to San Francisco, there was a throng of people in the hall waiting for some event to take place. Everyone was waiting for the roshi to arrive so it could start and people waited and waited and suddenly I saw Suzuki Roshi in the crowd, looking helpless, waiting with his hands dangling then someone else saw him and told him we were waiting for him. I don't know why, but it was deeply touching to me. It was because of how little he made of himself. It was so symptomatic of the man.

I always felt totally at peace around this man, especially in my apartment or during dharma talks at Tassajara. I felt I always completely understood him, that he said what I was thinking and had been thinking for years, never any need to ask him a question or to discuss Buddhist matters - not once. I never with any of my teachers asked a single question or discussed Buddhism or any aspect of it with them. I always felt with all of them, including with Suzuki Roshi, that - happy is a silly word - totally at peace with them and that I understood what they were saying. But each was very different from the other and the one thing that attracted me to Suzuki Roshi was his humility that wasn't put on - it was natural, a natural shyness. And he came from a background like mine that was very stratified.

When Suzuki Roshi stayed at my apartment in New York which was huge and modern and overlooking the river and bridges - the Japanese guests loved that view because it was so expansive - we never discussed Buddhism but just did what we had to do. I remember once he was sitting on the floor at my living room table and he was writing a letter and I said who are you writing to and he said to my son in Vietnam. I knew that his students were all against the war and he didn't defend that his son was there - he just said it matter of factly.

At one point I went to get my cleaning tools and started cleaning my apartment and he went back to where I'd gotten things from and he got up and went back there without saying anything and came back with other cleaning materials and he just quietly went to work and we cleaned the whole apartment without talking. None of the roshis talk so I didn't either though I'm talkative. Suzuki Roshi was different though in that he'd do something like clean. Eido-shi would never clean - he'd have others do that and Soen wouldn't either, not because he considered it below him but because he was always in the clouds and more into the universal than the particular but he was very adventurous and when he heard that I'd traveled all over the US with two kids and a dog and a tent and a boat and that we camped in the mountains with bears he got very excited and organized the whole zendo to go camping. That was the kind of thing he did - more dramatic. I like that too but I felt so at ease with Suzuki Roshi. There was no need to say anything.

On that or another visit we were on a New York City bus and Suzuki Roshi was sitting on my right and some stranger was on my left, a younger man and he said is he a Buddhist monk? And I said yes and he said what type and I said a Zen priest and he said the great Suzuki! and Suzuki Roshi turned to me and said, "Tell him I'm not the great Suzuki, I'm the little Suzuki." That was typical of him to say something like that.

I had a little altar in the living room with a window behind it revealing the city and the sky and Soen Roshi was a great one for very non conformity - he always had new ideas to shake things up. Like I had the curtain closed partially to show the altar so when he came in the morning he'd open them and I closed them again and we did this always when he came. He'd found a couple of huge mushrooms on his camping trip and he put them to the right and left of the Buddha and they were showing the inside to the Buddha. I enjoyed Soen and he made all kinds of hocus pocus and it was interesting but kind of a little bit weird - too dramatic.

Two weeks or so later, Suzuki Roshi was staying at my place and I was telling all about Soen and the camping and the mushrooms and I was sort of full of it and the next morning at zazen - we always did zazen in front of the Buddha, I came in and Suzuki Roshi had turned the mushrooms the other way around and I never said a word because I knew he meant don't get hung up on what he or I say and the next day I put them the other way around to show him I knew it didn't matter.

I had been studying the tea ceremony and was doing it for Soen Roshi and I couldn't afford to have enough rugs in my apartment and didn't clean the floors before he came so my feet were dirty and my white kimono picked up dirt when I sat down and he laughed and laughed.

When Suzuki Roshi was there I had set up a trey in the back of the kitchen with everything ready but I never served tea because the opportunity had not presented itself. His wife and I did the tea ceremony for each other in San Francisco and he walked into the other room and I remember thinking he does this so often he can't take it another time. I had been with him to visit the Johnstons and Millie was so hung up on tea ceremony and she did it once and Suzuki Roshi said that was so wonderful and so she did it again and then again which was very insensitive of her. He'd seen it many times and you don't do it over and over and so I said Roshi has to go and we got out of there and he said, "You know how to take care of me."

The poor man had to sit there and he had been coughing like crazy and whenever he had these attacks of coughs I'd call San Francisco and tell them he was seriously ill and to take him to a doctor. I'd tell him to lie down and I babied him a little bit.

So I had this trey and he'd noticed it and I'd never bothered him with it and before he left out of the blue he said to me - you're a great tea master. It was because I didn't make him go through it.

He had that kind of humor and he left it up to you to figure it out. But he wouldn't say it unless you could figure it out. He had an uncanny understanding and would find the right moment to say the right thing and that was another thing that made me feel very comfortable about him.

He asked me what year I was born in and I told him and he said, "Ah, the year of the pig."

We would take taxis in the evening and busses in the day and we were waiting for a bus and he said, do you do koan Zen or shikantaza, and I said, shikantaza and he said, I thought so.

Someone asked him what Soto Zen was and he said it was farmer's Zen.

We went to visit the New York Zendo and there was tea and someone asked him what is karma and Suzuki Roshi was first quiet as he often was and then said, "Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as karma."

Suzuki Roshi as well as Soen told me to sit alone or start my own group for women. Do you remember Margo Wilkie? I visited her in her apartment in New York and she and a couple of ladies had tried to sit together but they didn't know what to do so Suzuki Roshi said at a lunch one day why don't I start a group with these ladies and I feel bad about it but I lacked the confidence and it seemed to me like a huge responsibility. I know now that people teach by example and not by talking. I remember when Baker Roshi was installed I sent a card saying what an awesome responsibility he had.

Suzuki Roshi and Tim Buckley and someone else were sitting at my dinning table in New York and Suzuki Roshi said that this is the way it should be - having three men to one woman was the proper balance - that woman shouldn't run the whole thing. I just noticed it but I didn't make anything of it. I chalked it up to Japanese culture, it's something they all had and in Germany too.

When Baker Roshi would come he'd use the phone for thirty minutes and then leave again. I was very disappointed when he was made Roshi. He didn't have the right temperament and was too attached to superficial social things and name dropped and I didn't like his lectures. I knew his father well and traveled with him. I knew where Dick came from and he couldn't help being who he was. He was the absolute opposite in every possible way from Suzuki Roshi.

I don't blame Suzuki Roshi for conferring upon him the title. He was dying and knew some of the shortcomings. He once told me, Dick always wears socks that are too long with his kimono and can you go and buy him some socks with me. So we went to an American men's store on 86th street and bought a half dozen pair of white socks for Dick. And we went to the Village and bought a big wooden fish which is hanging somewhere at Zen Center and he was so happy to discover it. Someone else paid for it - I can't remember who.

I gave him my bed to sleep in in my room and I had a big shepherd and the dog had a way of rocking and would sleep against my bed and with Suzuki Roshi he'd go sleep with him in the same way and it was a big honor and I got a kick of it that the dog felt comfortable around Suzuki Roshi.

I remember one of his talks at Page Street he commented on how people were going to such lengths to decorate their rooms in the most Japanese style and he said, if you want to be really Japanese, you have to be really American.

One day I was at the end of my stay at Page Street and I was going to fly back to New York City on a night flight but there was a guy whose name was John Hopkins who was visiting and who was a friend of Issan and he was going to take me to the airport and so I went to the last sitting at Page Street and snuck out at the end because I had to go and I got my stuff and by the time I was out in front and about to get into my car, everyone was pouring out of the building waving goodbye and Suzuki Roshi was standing out on his balcony of his apartment waving with a dish towel. I think that was the last time I saw him.

When I first came to Tassajara I came as a work student and sat tangaryo and then I worked half a day. I went there once or twice and would go to Page Street sometimes. And I'd work in the kitchen. I was at Green Gulch a few times.

I have trouble remembering because everything teaches. I've tried to be more humble but I can't because I'm from a German background and there humility is considered a weakness. It's more British - always underplaying yourself - that's done in England and somewhat in America. In some cultures you show the opposite but in Germany, Denmark, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland and toward Russia people are very direct and it's painful but everyone does it. But Suzuki was direct in his own way. And I am by nature shy but I try to talk it away with people but with the Buddhist teachers I can be shy. Tai-san would stand in an arrogant posture with his legs apart and his arms folded but Suzuki Roshi would just stand there with his arms dangling - very guileless, almost - what's that word?

Loly Rosset's memories of Europe

The tape of Loly's European memories was returned to her the day after the interview for her family to hear. I took these notes the night of the interview. My mate Katrinka and I've visited Loly several times at the Redwoods, a retirement community in Mill Valley, CA, and on one of those visits she gave me that tape back so some day I plan to transcribe it word for word, but this seems fairly thorough.

It recounted her adventures during the Nazi regime which began when she was drafted at the age of 16 to work on a farm where she lived in unheated barracks with other Germans and worked with them and forced labor from Russia and Eastern Europe. She came from a town in Germany near the Dutch border. Her family had some money and was well educated. Her father had been an officer in the army in WWI and had to go back in for WWII - he said, don't worry, I'll be back in a few weeks before he went off to Poland I think it was.

After a year there she went to Paris where she worked for the German daily paper which had grown quite large. Everyone on the paper but for a couple of people were strongly anti-Nazi though they were careful what they said around whom. She hung out in Paris with Parisian artists and intellectuals and was watched by the authorities and suspected of being a spy. Because of that the paper was supposed to send her back to Germany but she finagled a job with some French whom she learned later were in the underground.

She went back to Germany after a while but soon went to Belgium where she also worked for Belgians who were in the underground - she was too young and naive to realize it though. They used her to get info from the German embassy or whatever. One day she went there and the Germans were all gone. The Americans were coming. This was shortly before the 20th of July when the German army officers tried to kill Hitler - we thought, she said, for a few hours that they had succeeded.

She knew she'd be safer in Belgium but her sense of duty compelled her to try to go back home. On the way the customs agents made her get off the train with her luggage and she had to see an SS agent who was drunk and abusive and asked her why she had no departure stamp on her passport. She said it was because everyone had left to flee from the allied forces. The officer accused her of spreading false propaganda for the allies and pulled out his gun and pointed it at her. One of the customs agents jumped him and the other took her away quickly around the corner to a bus stop where she got a bus.

"I made it to Germany and it saved my life. This sort of thing was not unusual. These things happened to millions of people. And this is not the worst. As a background to being a Zen student, as a perspective, I think like Japanese who went through the war, we had a different context than the Americans. I've always been philosophically oriented. But not because of the war only - my grandfather was a Buddhist intellectual professor. He was the head of the University of Cologne and he had founded it together with Adenauer but the Nazis put him out of business because of his international connections. His name was Christian Elkhart. In 1933 when Hitler came to power, very few were put out of office but he was not allowed to teach from then for the duration of the whole Nazi time. I was his favored grandchild and we dutifully wrote to each other and his letters were always censored, long sections blacked out - I grew up with people spying on me.

Later, under Yasutani Roshi, I looked back on that and tried to explain to people how I felt - it had a profound effect on me, especially almost being killed. I couldn't put into words what this meant to me and what I learned about life from this. It had a very profound effect on me.

I went to see my mother and moved in with her in a tiny village and you had to do something so as not be sent to be on an anti-aircraft unit which no one wanted to do and there was a little furniture company which had been converted to building parts for airplanes. I carried by myself all the furniture out of the factory and cleaned all the windows. I was skinny and strong. This was in a little valley and we could hear the war coming close, could hear echoes of the fighting. We were at an inn on the crossroads of two country roads and we went out at night and removed the mines from the roads and we hung white sheets out the windows and the Americans came in big trucks - I don't remember tanks. I was the only one who spoke English and I told all the Americans for us, told them we welcomed them and there was a big black soldier and we'd never seen a black person and I went up to him and hugged him.

At that point I decided to leave on my bicycle and headed toward Switzerland where people had been falsely told on the radio they could get sanctuary. My mother was adventurous and had been a stunt pilot. She was like a man more, she also was a lesbian. She was elegant, handsome and tough. She lived with my father's female cousin after divorcing him for many years. So I rode my bike but as Germans we weren't allowed to leave at all more than two miles from where we lived or so but I went into the French Occupied section. I went mostly through the fields and forests but every now and then I had to go through a village and there would be military police who would ask where are you going with all that stuff on your bike and I was wearing my French sheepskin coat and I would answer in perfect French toward France!

I remember being at a train station and there was a rumor that a big train had disappeared - with lots of cars. They were French at the station and some were suspicious and saw my passport and saw I was German and had been in France and we had dinner - there were six of them and they were drinking a lot and some thought I was alright but some didn't and I slept in a room with an armed guard but they let me go.

[I knew] some Italian who had been slaves to the Germans and the war was not over and we plotted to get out. We slept in the woods and before dawn we sneaked around the border guards into Switzerland and went into a village but all the dogs started barking and we went to the fountain in the center of the city and I was caught by some Swiss border guards behind some bushes and they saw my passports - the others were okay but I was sent back sobbing and pleading into Germany."

There she ended up in a section run by the French Resistance Army, the 152nd French regiment. "They were called the Red Devils and I wore their insignia. I had gone to their office to get permission to move on or even to stay - I was a no one - but when they heard my French they all crowded around me and they said they needed an interpreter and offered to house and feed me. I ate three meals a day with French officers. They put me up in the local Catholic church so the locals wouldn't think I was sleeping with them.

One day I was in my room and all of a sudden there were gun shots outside the window and they called me and one of the officers kept saying, "Loly!, Loly! La Guerre fini! The war's over! They had me shoot the guns with them at bottles and they were shooting out of windows and a German in a field got killed and so I celebrated the end of the war with the French army. What was important to us, what we discussed, was how crazy the war was and one of them was a nephew of de Gaulle and we were from all kinds of classes and walks of life but they'd all been resistance fighters so they ignored social differences and in Europe there are sharp differences between the social classes. We all had the same quarters and ate together. We were all so happy and equal.

After the war times were hard, there was total chaos. A French convoy escorted me to the next sector and told them I was okay, I'd travel in trucks with soldiers and I hitchhiked and an American officer picked me up and he put me up at the officers quarters for a few days and I had corn flakes for the first time and thought they were the greatest food in the world and a soldier from Texas serenaded me from under my window and another played tennis with me and they gave me suitcases filled with all those things we didn't have like soap and toothpaste and food and goodies and the officer drove me far off to my home.

Experiences like these offset the horrible ones. I went to Bremen on the North coast and worked for the American forces radio station. The director and his family sponsored my coming to America. I'd baby-sit the transmitter at night and wrote poetry and studied fine arts at an academy there studying sculpture. I can still feel the clay in my hands.

I got more and more involved with arts and the best place at the time was in Munich and I was accepted as a master student to a famous sculptor. I met my first husband there who studied theater scenery design. There I rediscovered my interest in oriental art. Most of the academy was bombed out with no roof and marble staircases going up into the air to nowhere. There were all these sculptures of famous people from the past and we cooked on hot plates and slept on the floor or on a couch.

My husband, Wolfgang Steiner, (who later married an American shipping heiress and came to America and later shot himself - he had been shot in the eye during the war which affected his brain and when he drank too much he'd get very aggressive - he was an alcoholic) and I got a larder - we got married so they wouldn't throw us out.

I was working for the British foreign office there. This was 48 or so and I got pregnant and got a big box of food from the council every week but he left and we got kicked out because there was a Nazi there who didn't like us and my husband had an affair with a famous actress. My husband worked in the theater for free - people were happy to work for nothing, just to be able to work was good. My husband took me to the country to have a baby with a midwife and the baby was born ill, covered with pus and the midwife was horrible and yelled at me to control myself and the baby just sighed and the baby was kept next to me which was wonderful. The baby got sicker and sicker and died in several months.

My husband and I had applied to emigrate to many countries - America came through first but we got divorced but remained friends, even with his new wife.

I was doing translation for the American paper in Munich. I eventually arranged for my emigration alone but on the train to the boat my papers were stolen. I knew that bad people hung out at the stations and I guarded my passport and papers in my bag and guarded it under my arms with my luggage but some unsavory character popped up from down in the tracks when I started to board - I was the first in the line. He held the two bars so I couldn't get in and people didn't see him and pushed - this was their trick.

In the train I looked in my pocket book and my papers and passport were gone and I threw my bags out and jumped off the train. The French council got me new papers with the Americans and I made it to the boat at Hamburg, a tiny freighter. There were only twelve of us on the freighter and it took several weeks to get to America and we got into a hurricane and finally we got to Wilmington in America.

I visited with Loly at the Redwoods Retirement Community in Mill Valley a few times, once with Katrinka. The last time she gave me back the tape of her memories of Germany and the war. It is not yet fully transcribed but of course it will be. I did the above transcription hurriedly the evening of the interview. The reason why is interesting.

Loly had come to my apartment in the Gerstle Park section of San Rafael, close to where Katrinka and I are living now. We sat in the living room and I urged her to say whatever came to mind. She proceeded to talk for a long time about her experiences in Germany as a young woman. It was fascinating. When she was through with that we took a break. I stood out on the back deck and smoke a cigarette, something I still did off and on back then. Then we went back in and she talked about her Zen history for a long time. It all went smoothly.

That night I got a call from her. She was agitated and said she wanted the tape of her interview back, the part about Germany. She seemed distressed that she'd talked about all that. I said sure and she said she'd be by the next morning. I sat down and transcribed the gist of it in an hour or so and gave it to her the next morning. Again, she seemed upset and had little to say except that she wanted to go over this material with her son Peter.

Then I got a call from my agent friend Michael Katz who said he'd run into Loly at the grocery store in Mill Valley and that she was very upset with me for making her talk about her past in Germany and having no interest in her Zen experiences. I told Michael I hadn't drawn that out of her, she'd been almost possessed about telling that story. She did say something about how she'd never told that whole story before. I also said that she'd then gone on to talk a great deal about her Zen history. He also said she'd complained about me being too informal, not lighting incense, and taking a break to smoke a cigarette. I said I should have been more sensitive.

Loly called me up and went through that same line of thought and said she had prepared to talk about her Zen history and wanted to come by and do the interview we should have done in the first place. I transcribed her Zen interview and printed it up in preparation for her visit. She came, I lit incense, and she took out her notes. She went through all her notes and I showed her that everything she was saying I already had from her. She had no memory of having said it. She left both satisfied and mystified.

My take on all this is that Loly was traumatized by going over her experiences during the Third Reich. Ten years later or so, she gave me the tape back of the German part of her interview and it was no longer a big deal. - dc - 7-20-12

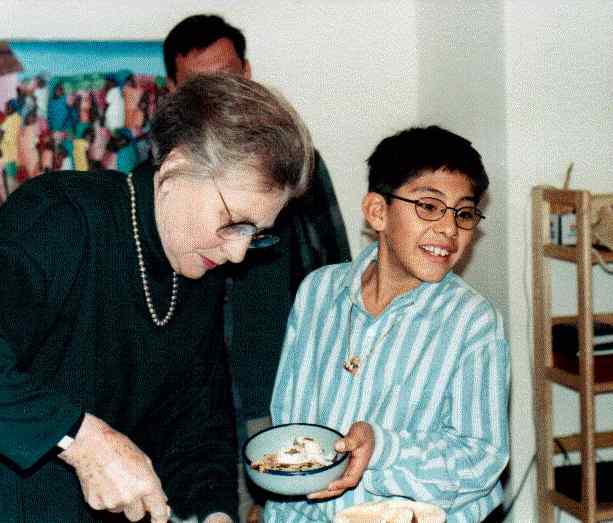

Recent photos of Loly sent by her son Peter (posted 7-21-12)