|

Interviews

|

|

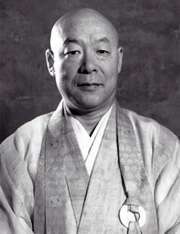

Eido T. Shimano Roshi

Eido Tai Shimano founded the New York Zen Studies and Daibozatsu Zendo See links at the bottom of this page Eido Tai Shimano died February 18, 2018 in Japan. The Death of Eido Roshi, Problematice Pioneer - Tricycle

Eido Roshi trained in Japan under Soen Nakagawa Roshi, and came to the United States in the 1960s. He began holding zazen meetings in a small apartment on Manhattan's Upper West Side, and with help from his sangha and supporters opened New York Zendo Shoboji in 1968. Four years later he received Dharma Transmission from Soen Roshi, and on July 4, 1976, Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongoji was dedicated. The Interview I enjoyed my few hours at Daibosatsu with Eido and appreciated what he had to say. I'd met him in 1968 at Tassajara when he came with a group of Zen teachers to visit - Soen Nakagawa, Yasutani. Rode up to the road in the back of a pick up truck with him to join Soen Nakagawa and others to spread some of Nyogen Sensaki's ashes. He was more into a sort of macho Zen trip then. I remember him saying, "There are two types of people. Those who know and those who don't know." More on this visit of teachers to Tassajara which includes this link to an article on the teachers' visit and one on Eido Shimano opening NY Zen Studies zendo in Wind Bell 68-3-4. DC--I'd love to hear your memories and impressions of that time. Anything you recollect about Shunryu Suzuki. Or anything you want to say about that time or the relationship. He was always very supportive of Soen Roshi and you. Eido Roshi: I don’t know how to order my memories, but anyway, I think the first time I met Suzuki Roshi was Bush Street. Must be early ‘60s. 1962, or -3 or -4 – that I don’t remember. My first impression is he was very natural. Not formally dressed, not formally burning incense – he was very natural. He put formality aside. That was very impressive, because I was brought up in the Rinzai establishment where formality was very important. Especially in Japanese Rinzai Zen. And coming here to America and meeting Suzuki Roshi, he gave me a natural warm welcome, without formality. That is my first impression. DC: Was that when you first came? ER: I came to Hawaii in 1960, so San Francisco was 1962 or -3 or something like that. [Eido was Dan Welsh’s roommate in Hawaii for half a year. Dan was studying Japanese preparing to go to Japan to Ryutakuji to study with Soen Nakagawa Roshi, Eido's teacher. And Eido was studying English and preparing to go to America. Eido remembers Dan’s parents came. And he remembers his father who loved to meditate, but not in the Zen style. Dan’s parents were Quakers.-DC] ER: The second time I met Suzuki Roshi, and the second impressive thing about him – the second time I met him was when we had a sesshin outside of San Francisco conducted by Soen Roshi and Yasutani Roshi and I acted as Jikijitsu [head of the zendo I think--DC] and translator, and so on. Suzuki Roshi knew what we were doing and encouraged his students to attend our sesshin. [I have had a few people tell me this in interviews.--DC] And that open-heartedness was another important memory. I learned a lot from that attitude. DC: That was ‘65, I think. ER: And then around 1965 or ‘67 [67--DC] I’d been in New York for awhile, but I went to the West Coast at least twice a year and had sesshin in the Los Angeles area and the San Francisco area. And all the students who attended the sesshin in the San Francisco area wanted to go to Tassajara which had just opened. One of the students asked me to talk to Suzuki Roshi to get her admitted. She had submitted an application but had received no answer. So I went to see Suzuki Roshi and he said, "I ask the students to take care of everything." The implication of that is that he trusted what the students did. Another implication is that the less he did, the more they would do. DC: So did she go? ER: No. She didn’t go. It wasn’t my fault or Suzuki Roshi’s fault. DC: It was her fault because back then we accepted everybody. ER: Oh really. DC: Sure. They probably just lost her application. ER: If I have a chance to see her, I’ll tell her. She was very hurt, but she did what she could do and she asked me to talk to him and she wasn’t accepted. DC: This is amazing. It seems almost rude to me that he wouldn’t take care of this request of yours. ER: It was a good lesson to me. In those days I was contrary. I did everything by myself, but the more I did the less students did. Nowadays, at last I am getting old [laughing] – getting into my old age and I have no choice but to do less. DC: You don’t look very old. ER: Compared to thirty years ago. DC: You look good to me. ER: To continue the Suzuki Roshi’s stories. The next one is we were doing sesshin outside of San Francisco and Suzuki Roshi had just spent 90 days at Tassajara doing sesshin [DC: actually he’d just been there during the summer guest season.] and his wife was quite upset and was complaining to us. The day came and she went to pick him up with another student. [DC: That’s not really what happened. She was at Tassajara. Yvonne just went to pick them up. But anyway he didn’t know because he saw them on their way back.] On their way they came to see what we were doing in sesshin. This is another impressive act, because the dharma teacher respects dharmic activity even though he was on his way back to San Francisco. He came to our place to spend a couple of hours with Soen Roshi and Yasutani Roshi. That effort was – unforgettable. It happened in 1968. This I remember clearly. We opened our New York City Zendo on East 67th Street. It was a carriage house and we changed it to a zendo. It was September 15, 1968. I sent an invitation to him to attend the opening ceremony and he was almost – not so sure – it was possible that he would come. I was hoping that he would show up, but instead a huge rock came from Tassajara. We went to Kennedy Airport and picked it up. DC: Yeah, it was a big box. It weighed 650 pounds or so. I remember Suzuki-roshi finding it in the creek and Paul Disco building a box for it and we put it on the truck at Tassajara. ER: It came by air mail so I interpreted it to be Suzuki Roshi’s manifestation, and I treated it as though it was Suzuki Roshi. This was when my first zendo was opened. Soen Roshi, Yasutani Roshi, Sasaki Roshi, Maezumi Roshi came. Right after that, four days later, the benefactor of Shoboji, Chester Carlson, passed away on September 19. I interpreted his passing as that he sacrificed his life to that zendo and Tassajara as well. His funeral was held at Rochester at Xerox headquarters. His wife asked me to say some words. I was surprised she asked me and not Suzuki Roshi or Yasutani Roshi. Suzuki Roshi was there with Dick Baker and Suzuki Roshi was prepared to do the service. He brought equipment from San Francisco. After I spoke, Suzuki Roshi asked, "Did you give Chester Carlson a dharma name? Kaimyo?" Yes, I said. He said, "I’d like to have a service for him." I said his name was Daitokuin Zenshin. "Since you gave him that name," he said, "it’s better that we use the same one for Tassajara. The American way is so simple. I’d like to have a copy of his Kaimyo because I’d like to do a memorial service." I don’t know if you do commemorations, memorial services, for him any more. DC: Oh yes, we do. ER: Oh yeah? His name is mentioned in special services. Daitokuin Zenshin Carlson Koji. [DC: Koji is layman.] That was 1968. At that time on the east and west coasts, at the same time, people considered Chester Carlson important as a benefactor. ER: Later [1968] a trip to Tassajara was arranged. The members were Soen Roshi, Yasutani Roshi, myself, Maezumi Roshi, Robert Aitken. DC: And Loly Rosset, and Yasutani’s son. ER: Nyogen Senzaki died in 1958 and half his ashes were buried in Los Angeles and half were brought to Ryutakuji, and they were there for a long time. On that trip to Tassajara we carried with us half of Nyogen Senzaki’s ashes that were going to Daibosatsu Zendo to eventually be buried there, here where we are. And that evening with the full moon rising, we were chanting the Heart Sutra, and one speck of Nyogen Senzaki’s ashes were spread on that peak near Tassajara. It was Soen Roshi’s wish. Nyogen Senzaki had spent so many years in the San Francisco area earlier in this century. Soen thought it was good to bring half to Los Angeles and another half to the east coast. I left one pinch at Tassajara. It was a full moon night and we were chanting the Heart Sutra. Brother David was there too. [DC: Soen Roshi made up a chant, too, and got everybody to chant it.] He did an invocation up there. I think it was ‘68. [DC: The chant Soen chanted is in the Wind Bell, I should look that up. It’s something whimsical and cosmic. I think this was July or August of ‘68. It’s in the book. Might have been right before the opening of his zendo, and we might have fixed that rock up and shipped it after they came. That could be checked in Wind Bells. I mentioned that rock thing to him and he thought maybe that was right.] ER: We bathed together. Suzuki Roshi, Yasutani Roshi, Chino Roshi. Chino Roshi was there too. I think that was the first and only time we met at one spot on one night. The following morning, as you know, we had short speeches. Suzuki Roshi talked, I think, Soen Roshi talked. I remember that one or two of them I translated. DC: Yasutani Roshi sort of scolded Soto Zen folks about forgetting about koans. I remember he said Buddha was born enlightened and you have to believe in reincarnation to be a Buddhist. ER: Anyway, that was an unforgettable evening. Years passed. Suzuki Roshi moved from Bush Street to Page Street. He got ill. His condition was getting worse and worse. So one day a student of mine and I flew to San Francisco to visit him. He invited me alone to his room. My student who is much older than me waited outside. So it was Suzuki Roshi and myself. Suzuki Roshi’s talk with me was unforgettable. First he said in a very comfortable way with equanimity and tranquility, "cancer and I are now good friends." Also he brought up the famous Zen koan of Basso – Sun-faced Buddha, Moon-faced Buddha – just like that situation when the head monk with Basso who asked Basso a question and Basso’s answer was Sun-faced Buddha, Moon-faced Buddha. Our talk was amazingly enough not at all serious. Death was approaching. He knew he would die. We knew he would die. But despite all the intense sadness, he was almost cheerful. I can’t understand it. It really meant something to me. It really surprised me. That was a big comfort to me in those days. Then about an hour later someone knocked at the door, and Dick Baker came in with two or three others. The way he looked at Dick Baker – that perhaps is called compassion. There was love and compassion when he looked at Dick. He didn’t say anything. Just the way he looked at him – his face and eyes – I thought, my goodness, this is called compassion. Then they got my student whose name is Sylvan Bush. He was older than me. Back then I was pretty young. All my students were older than me. [Actually, he had a number of younger students, but they had an older group than we did.--DC] ER: His Buddhist name was Korin. He and Suzuki Roshi met. Korin told me later, he said Suzuki Roshi asked him, almost begged him, please take care of Taisan – in those days I was called Taisan. He was so touched by Suzuki Roshi saying that, which I hadn’t heard. Therefore I was more touched. According to Korin he said in the future Taisan will be a man of the dharma, at least on the East Coast of the United States. So Sylvan felt responsible. I didn’t go to the funeral because I thought the only purpose would be to go when he’s alive. But always he’s in my mind. When "Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind" was first published he sent me this autographed copy [DC-- and he pulls out a first edition autographed to him by Suzuki Roshi, that was cool.]. So although I didn’t practice with him, I didn’t live with him, and I’m not his student, we shared the sixties and the early seventies in American Zen Buddhism together, and either directly or indirectly I learned a great deal from Suzuki Roshi. So in that sense I consider Suzuki Roshi not only as one of the great patriarchs of Zen in America, but also I consider myself as one of his hidden students. These are the main episodes. They may not be chronologically accurate, but what I said is true. DC: When you came to San Francisco to see him when he was dying, I had some memory you brought greetings from Soen Roshi. Greetings, or maybe a gift. ER: Not gift, greetings. I was asked to give a talk in the zendo there in San Francisco Zen Center which I did. I gave a talk on the Sun-faced Buddha, Moon-faced Buddha. That was about 1971. DC: Yeah, and if Dick was there it was probably October. ER: It was fall, I remember. DC: When you came, in terms of chronology, when Suzuki Roshi came and saw you and Soen Roshi at that sesshin, that was in San Juan Bautista, and he was on his way back to San Francisco from Tassajara in August of 1971. ER: What I remember is his wife complained about sitting zazen. DC: She was just complaining about him going to morning zazen and evening zazen at Tassajara. There were two periods of each. ER: I remember vividly his wife complaining. She said he’s been at Tassajara for three months. [Not really. More like six weeks that time.--DC] DC: Suzuki Roshi went there and walked in the garden with Soen Roshi and Soen Roshi made the tea. That was really his last healthy day. ER: I can’t quite remember the date. DC: It was like August 19 or 20. He saw you all there, then he went to the city, and he gave one last talk. The last thing he talked about was Soen Roshi. I have that in "Crooked Cucumber." He called Soen Roshi a Buddha. Very high praise. [I find the page in the book for him.] ER: When he died someone called me here during Rohatsu sesshin and we had a memorial service for him. DC: Suzuki Roshi studied koans with a Rinzai teacher one summer when he was young. I don’t know really what age, but I think pretty young. An old man, Yaizu, told me that that was Gempo Roshi who he studied with. If he had studied with Gempo Roshi he would I'd think he would have said so at some point. But Dan Welch told me an old guy in Yaizu told him the same thing back in the early sixties. DC: Do you know anything about that? ER: Suzuki Roshi’s early days. I asked him about the past. He wasn't really secretive, but he avoided the details of his early life. I realized I didn’t want to ask him. However, Yaizu is in Shizuoka prefecture and Ryutakuji is also in Shizuoka prefecture. There is the possibility that he went to Gempo Roshi’s place. If so I’m really happy because Soen Roshi’s Gempo’s dharma heir, and I’m Soen Roshi’s dharma heir, and then Gempo Roshi, Soen Roshi, Suzuki Roshi – DC: Whoever he studied with, he said he studied koan one summer with a group of fellow students and they all passed, and he didn’t pass. He ran in on the last day and the master passed him, but he really didn’t feel like he deserved to be passed. Doesn’t sound like Gempo to me. ER: One of the reasons I translated the Shobogenzo--my friend asked me, you trained in Rinzai, how come you translated Dogen? " I said, if you have clear dharma eye, even if you trained in koan practice, you can appreciate Dogen’s teaching – more than other way. Of course I appreciate Dogen a lot. I can have critical opinion about what Dogen said. And that is the reason why I translate and study the Shobogenzo. It’s really challenging. Getting back to Gempo Roshi – Suzuki Roshi never spoke of Gempo Roshi. But if he did koan practice, that intensity most likely helped his teaching – his understanding and teaching to western students. To state it very briefly, I think that he was a man of virtue and a man of benevolence. One reason why I say so, one day Dick told me this. Suzuki Roshi and Dick were staying in Rochester together. We were all in different hotels for Chester Carlson’s memorial service. Suzuki Roshi and Dick were in the same room, and Suzuki Roshi gave him something to read. No, Dick gave Suzuki Roshi a book to read. Dick went to sleep, and he woke up later to find Suzuki Roshi was not there, but there was a light in the bathroom. He found Suzuki Roshi in there sitting on the toilet and reading with the door closed so that he would not disturb Dick. These are the kinds of things I respect in the mind of Roshi. Dick Baker told me about this and I was very touched. This is Suzuki Roshi’s teaching. All these episodes are directly or indirectly -- from these I learned a great deal about his style of teaching. I thought this is what a teacher should be. And through these episodes I learned a great deal about his style of teaching. There may be people in this world who say bad things about him, but generally speaking this is not the case. When Baker Roshi left Zen Center, he could have quit, but he didn’t, he could have given up. But he created a new sangha, and he’s always teaching about Suzuki Roshi. Suzuki Roshi’s teaching penetrates into Dick. Suzuki Roshi’s teaching penetrates into Dick Baker and others. Otherwise people would not continue on the path – as there were many others. That’s where his contribution is major. Nothing was drastic. So penetrating. So gentle. Like soft spring rain penetrates into the earth, saturating it. That’s how I see his teaching style. Soft gentle spring rain. DC: Reading this in May 2016 I'm surprised not to find something Eido said to me obviously when the tape recorder wasn't on and that is that he was so impressed with Suzuki's humility. Eido said he wasn't humble, tended to be arrogant, and so that was a great teaching for him. The Zen Predator of the Upper East Side on Eido Shimano by NYTimes religion writer Mark Oppenheimer Review of this book: The Shocking Scandal at the Heart of American Zen - By Jay Michaelson in the Daily Beast Oppenheimer's NYTimes article:

|

Conducted by DC on June 26, 1999 at Daibosatsu Zendo in the Catskills a

couple of hours out of New York City. A beautiful Zen monastery modeled on

traditional Zen monasteries. See the website of his group, the Zen Studies

Society at

Conducted by DC on June 26, 1999 at Daibosatsu Zendo in the Catskills a

couple of hours out of New York City. A beautiful Zen monastery modeled on

traditional Zen monasteries. See the website of his group, the Zen Studies

Society at