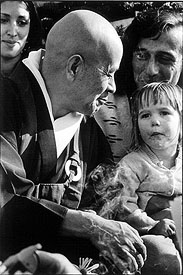

photo by Lisa Law Brief Memories

Patrick Woodworth Hi, David, First thought, best thought: Now, 42 years after I first saw Shunryu Suzuki at Sokoji one rainy Saturday morning in February of 1969, I find it difficult to isolate my own memories of him from all that I have learned since from the many people I have heard talk about him. Having begun to meditate on my own in Sacramento as I read Three Pillars of Zen, I wanted first-hand contact with a sangha and a teacher. So when I heard of Suzuki from Anne Armstrong, a psychic who lived in Sacramento at that time. I knew I had to find him. At that time, his sangha hosted a Saturday morning practice period beginning maybe a 5 am and continuing to at least noon, perhaps longer. That particular morning my wife and I were welcomed by a student and showed to cushions which I believe were located upstairs in a mezzanine above the main floor of what had been, I believe, a synagogue. In the early morning dark, I felt a deep intimacy with the steady rain falling from the eaves of the building. Breakfast was particularly memorable. It was served semi-oryoki style, at our zafus. We each got an egg in a small bowl, a mixed-grain gruel, and pickled daikon. I assumed the egg was hard-boiled so blithely cracked it on the edge of one of the bowls; the yolk drizzled onto my tray. I felt intensely embarrassed as I watched everyone else breaking their eggs into their gruel and stirring. Someone brought me a rag and helped me clean up, but I was off to what I thought was a pretty bad start at being a zen student. We sat several periods, did soji and then came time for lecture. That was really my first meeting with Suzuki. There this diminutive Japanese man sat before the gathered sangha sitting in the pews of the main hall. Actually, I remember him standing but I think that was at a public lecture he gave at another time. He stood, taking his time to listen to what needed to be said. At first I couldn't tell if the time he took between sentences was his effort to translate from Japanese or if it was his contemplation of the moment's arising. Probably it was a little of both. So this is what a master looks like, I thought. And, somehow, I wanted a spiritual teacher to look exotic. I would have found it hard to believe, at that time, that an ordinary American could have any spiritual authority. And the fact that I often couldn't understand major parts of what he said contributed to the picture I wanted to have of someone who might offer real insight into Mind. I have a vivid memory of him standing answering the question of a hippie with a huge head of red hair grown as an afro. He asked him about the acceptability of hallucinogenic experience in spiritual development. Suzuki was completely unfazed by the question and answered it with the same equanimity he might answer a question about bowing in ceremonies. His body was the answer. It was poised and equanimous. His actual verbal answer, which I can't recall, made little impact. There was nothing special about the question and nothing special about the words he used to answer. Here he was far from his Japanese home, at home in the fermentation of hippie San Fran. That was the answer I received and continue to receive years later. That summer my wife and I visited Tassajara for the first time. We stayed a few days, long enough to witness Suzuki at work in the stream bed of Tassajara Creek redirecting the course of the flow so it would follow the Tao he felt. I watched from above standing on a bridge as he conducted his opus. Eager young zen students grunted and huffed, levering stones into new positions. Then he would wrap his samue-clad arms around a boulder half his size and lifting and carrying it to a possible new location. It was clear that the result mattered not nearly as much as the shear joy in the activity. Judging from the smile on his face, he could have carried that stone from place to place all day and never grown tired of seeing it fresh in a new surround. That's about all I remember. The rest of my relationship to him is built on that. For years I had the picture that was on the dust jacket of the first edition of Beginner's Mind on my altar. Though I left the practice for long intervals, I returned to Green Gulch in the late nineties to sew a rakusu and take jukai. In 2003 I attended the Fall practice period at Tassajara with Reb Anderson. The practice has never left me. Suzuki's presence is like a mantra that may fade from consciousness but remains in the sub-conscious. Recently, Bruce Fortin, who met Suzuki around the same time I did, offered a seminar on Not Always So, during which he reviewed Suzuki's biography as presented in Crooked Cucumber. So his memory was refreshed in me. I suspect that refreshment, that sustained freshness was his essential message. It was there in everything he did, but especially in his astonished smile and laughter out of nowhere. Clearly, he was having fun. That was spirituality that could sustain a lifetime. I'm nearly 70 now and just sat ;my umpteenth sesshin last week coming away refreshed and glowing with the ordinary. |